How the Body Makes Marks: Toward a Somatic Shift in Architecture is an exhibition of research, designed by Jader Tolja and conducted by Galen Cranz and Leonardo Chiesi, on the relationship between drawing, design, and somatic experience. The exhibit, curated by Chelsea Rushton, ran in the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley, from April 2-21, 2018, and continues online here. Scroll to learn more.

THE RESEARCH

We experience architecture with our whole bodies, not just our eyes. However, contemporary architecture is commonly and increasingly designed for visual impact and without regard for the rest of the body.¹ This convention in architectural design can be attributed to a number of social and cultural factors, not the least of which is the technology architects use to design their projects. The development of CAD (Computer Aided Design) and the subsequent advances of this software have largely eclipsed the practice of drawing by hand to envision a project in its early stages.

Historically, drawing has served as an invaluable tool in the initial stages of design processes. Drawing by hand promotes thinking, feeling, tapping into intuition and memory, exploring ambiguity and chaos, and surrendering preconceived ideas and plans to the drawing itself and the often surprising directions it takes.² Contemporary architectural sociologists Galen Cranz and Leonardo Chiesi consider drawing an important conveyor of information; they use the triune model of the brain to investigate different sources of design inspiration.

The triune model of the human brain states that the brain has three levels: the brainstem and cerebellum control involuntary activities such as respiration and organ function; the limbic system processes emotions and memories; and the neocortex plans and performs higher cognitive functions. The first two layers of the brain communicate with the neocortex non-verbally, through emotional responses and images.³

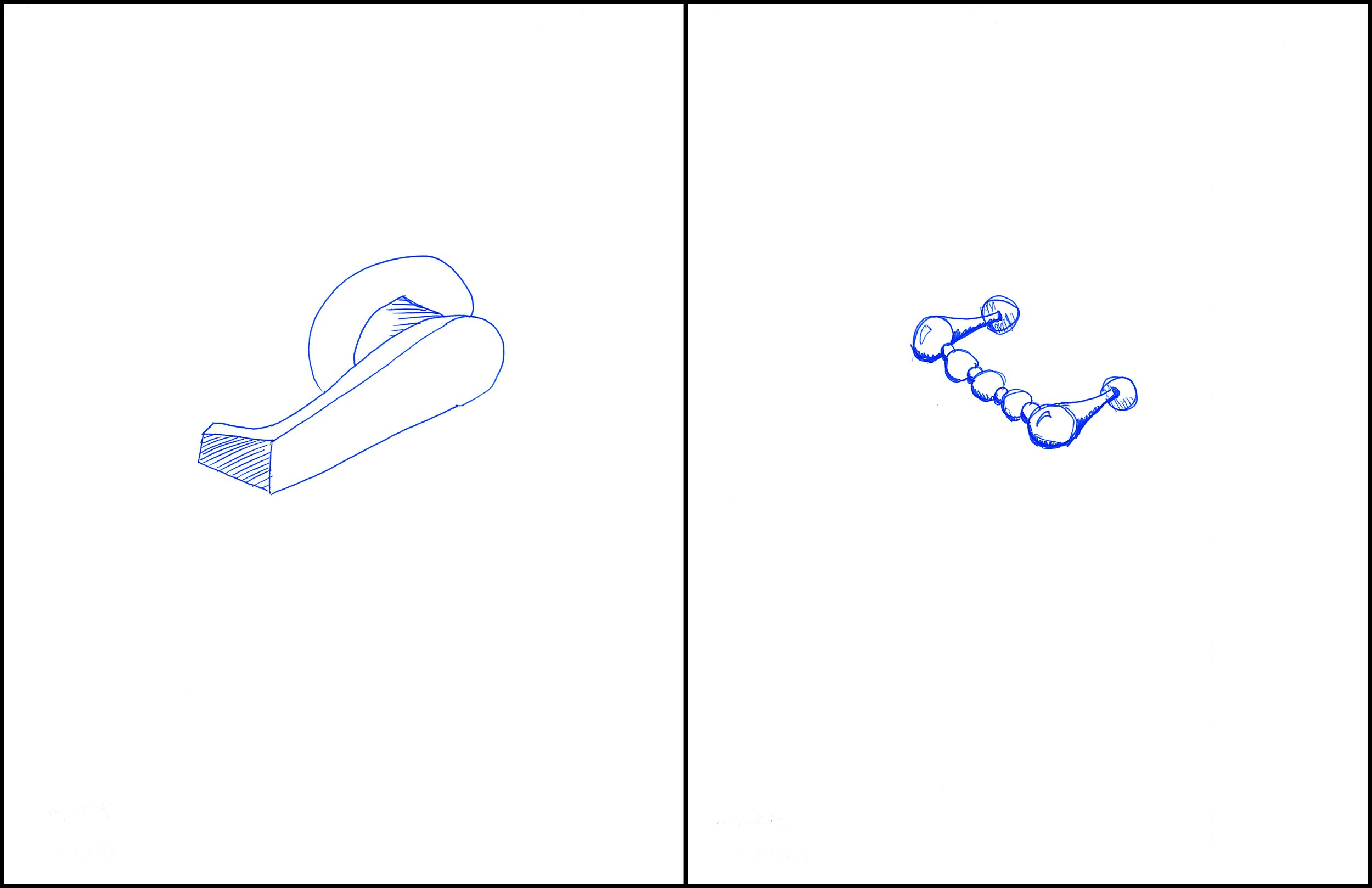

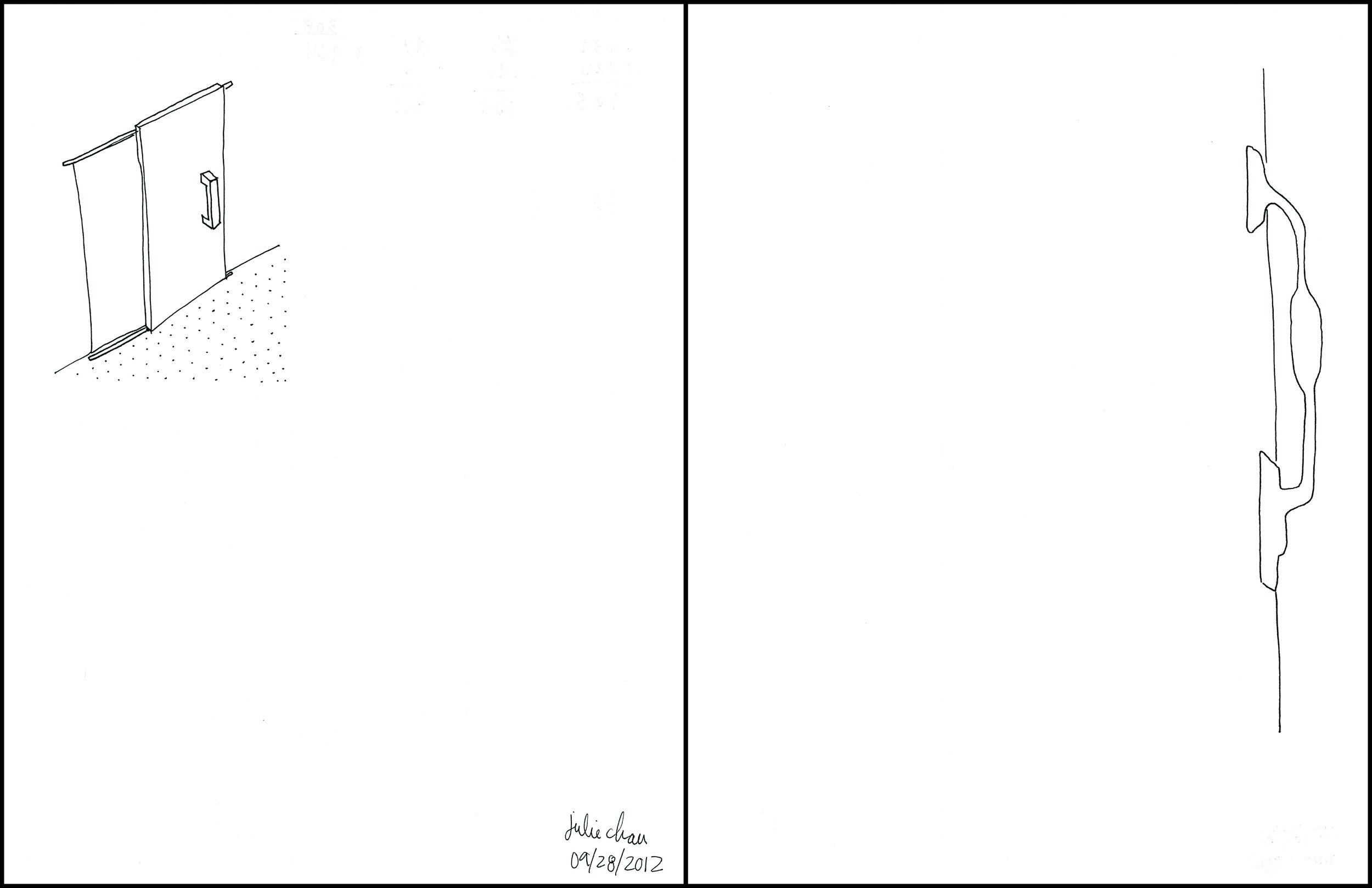

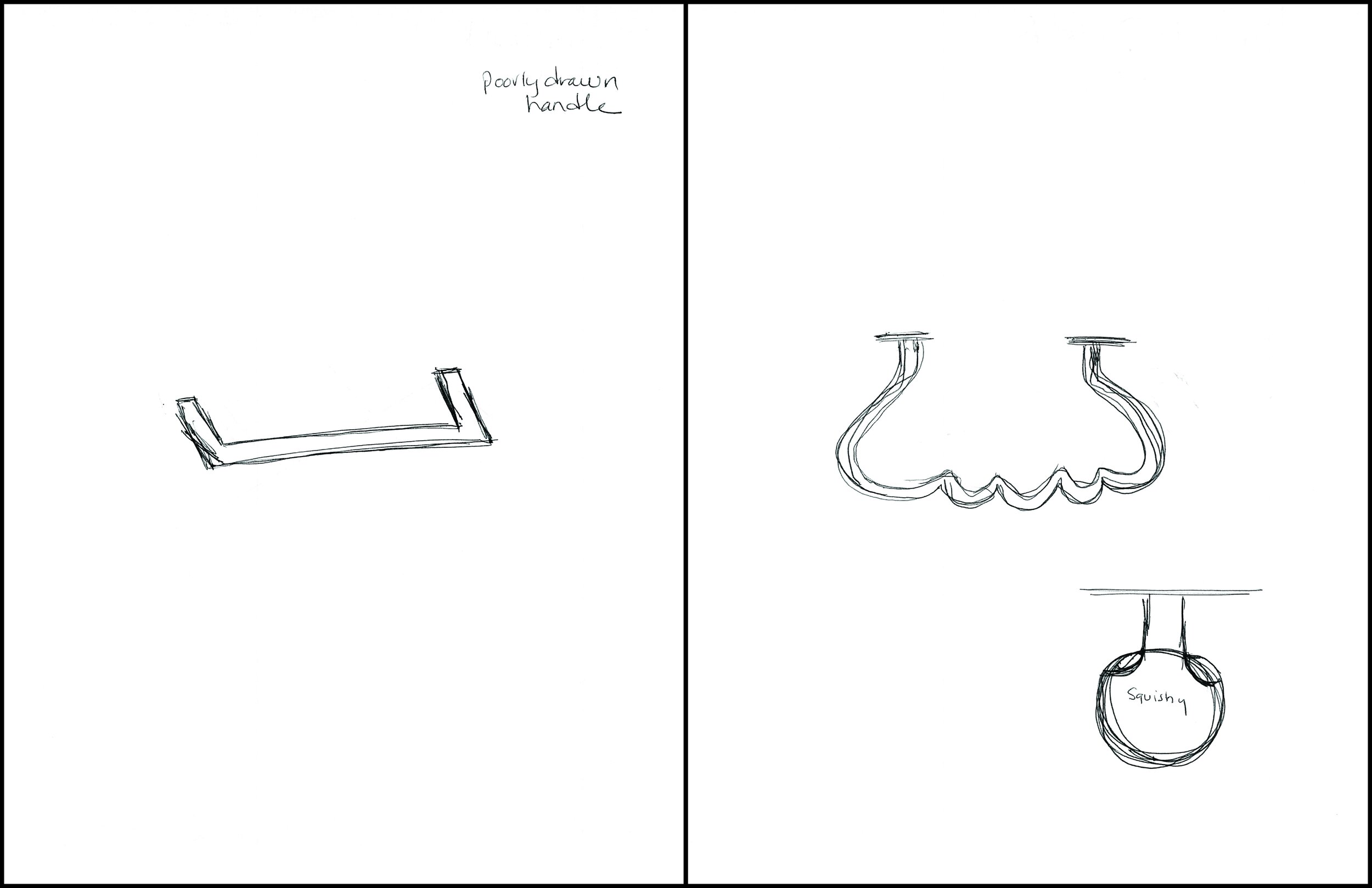

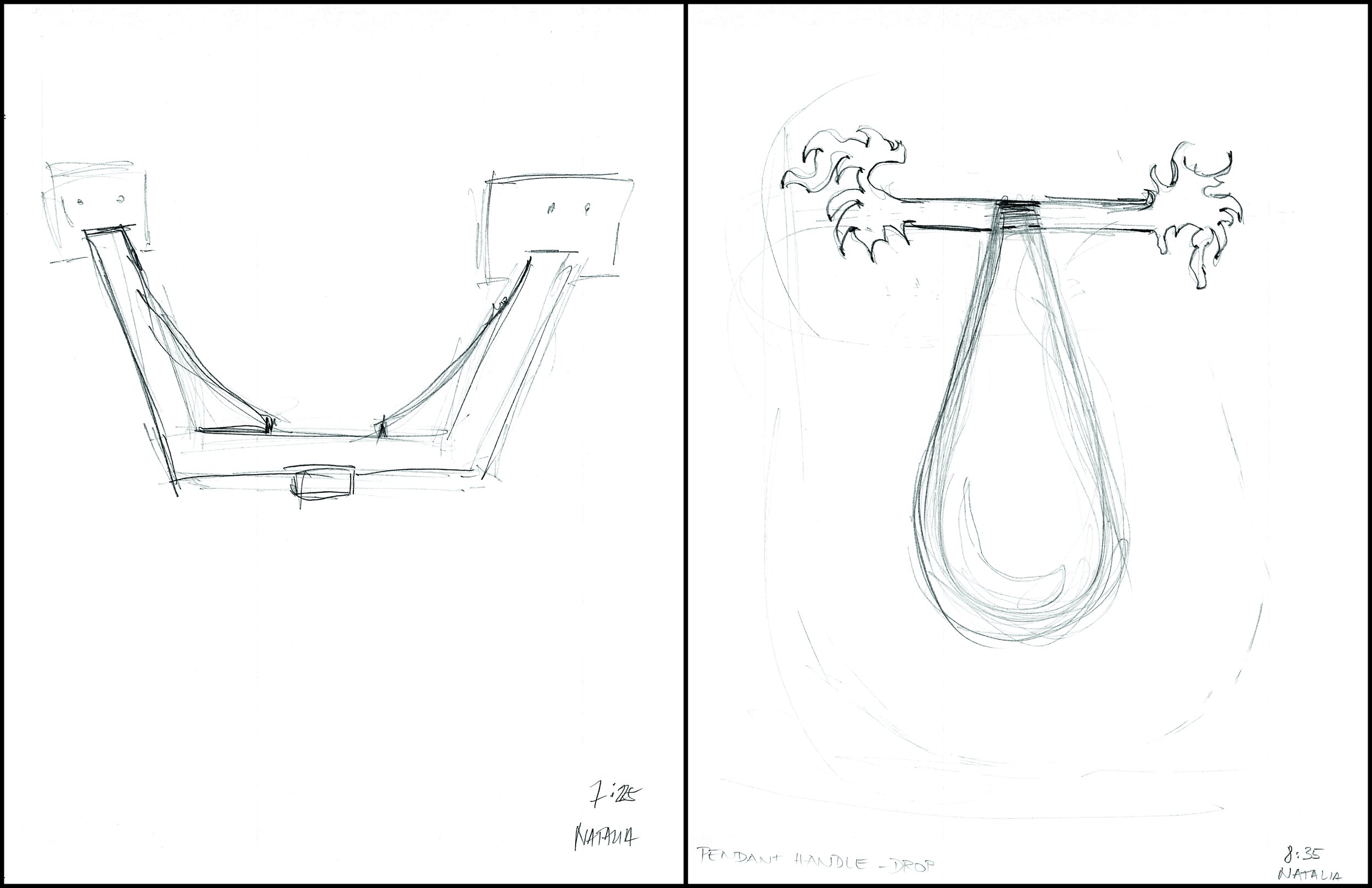

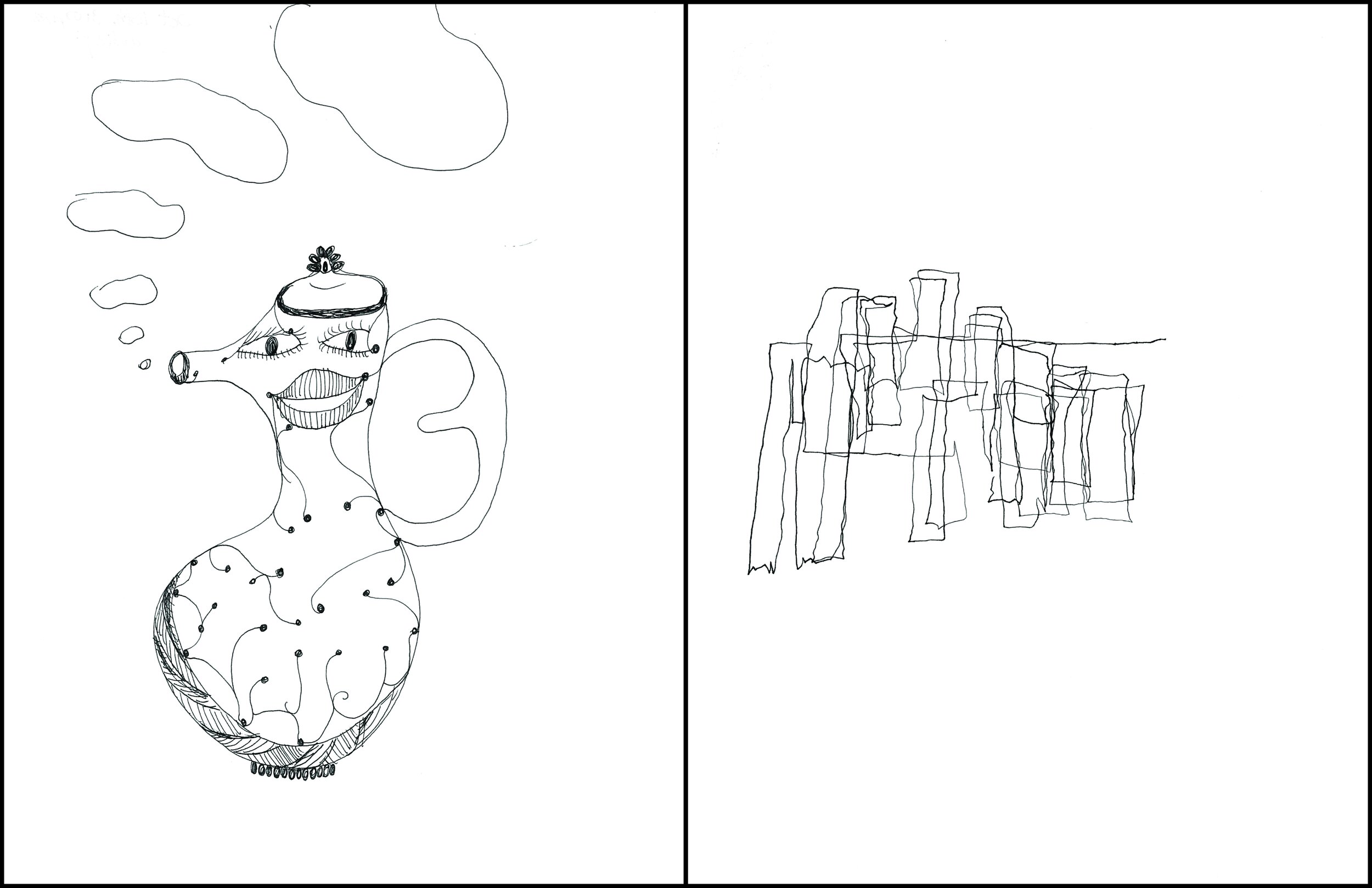

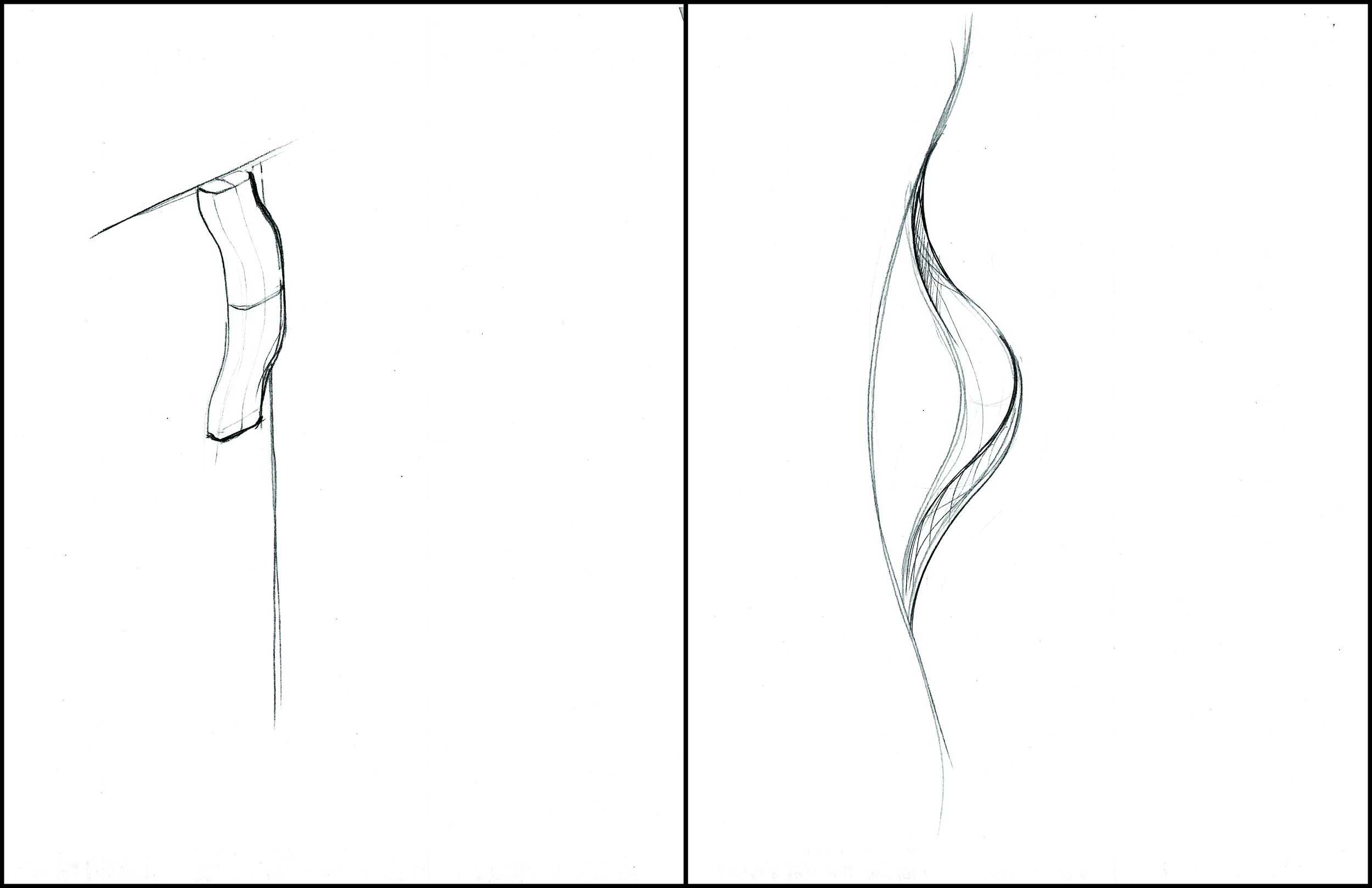

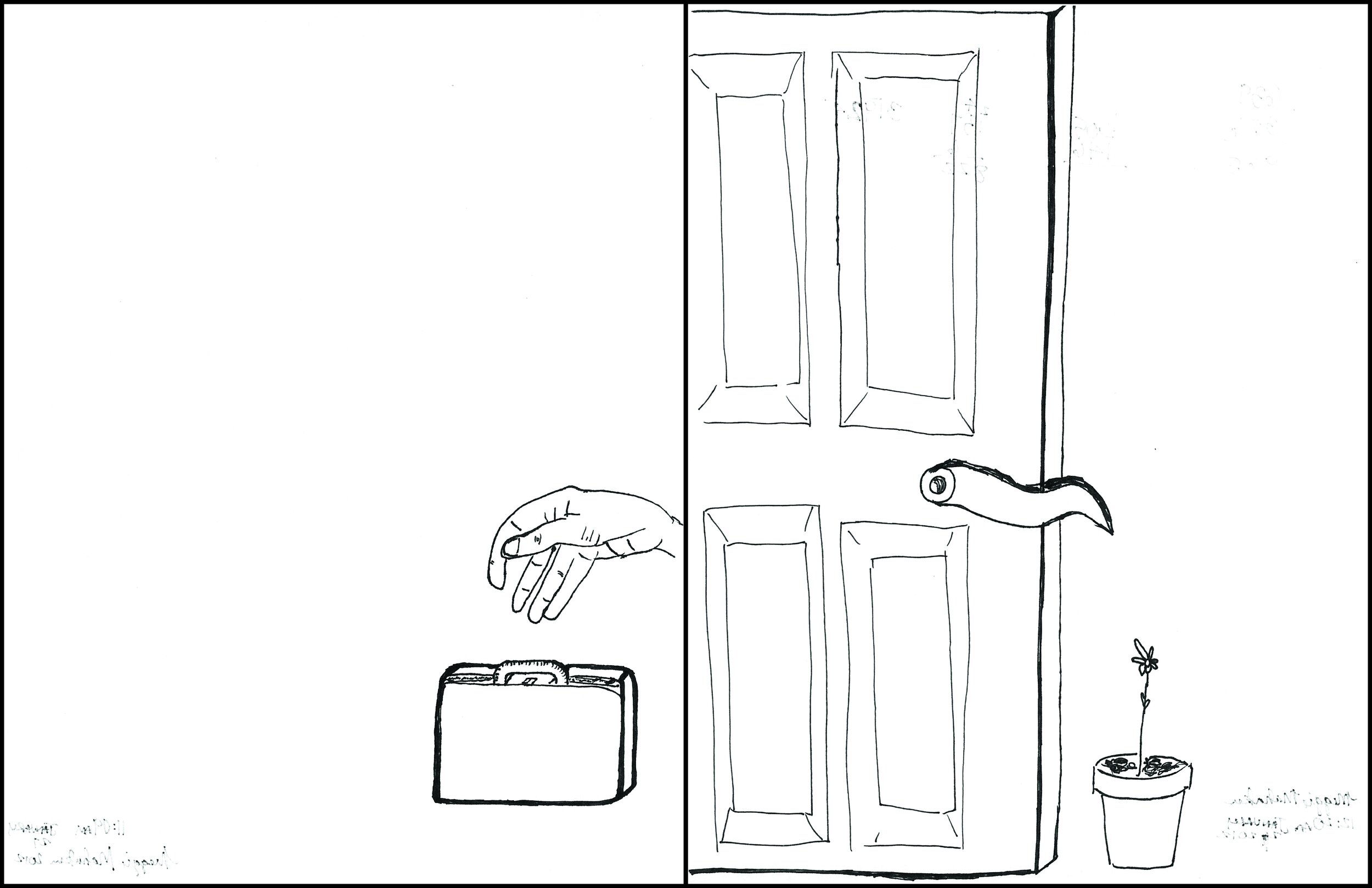

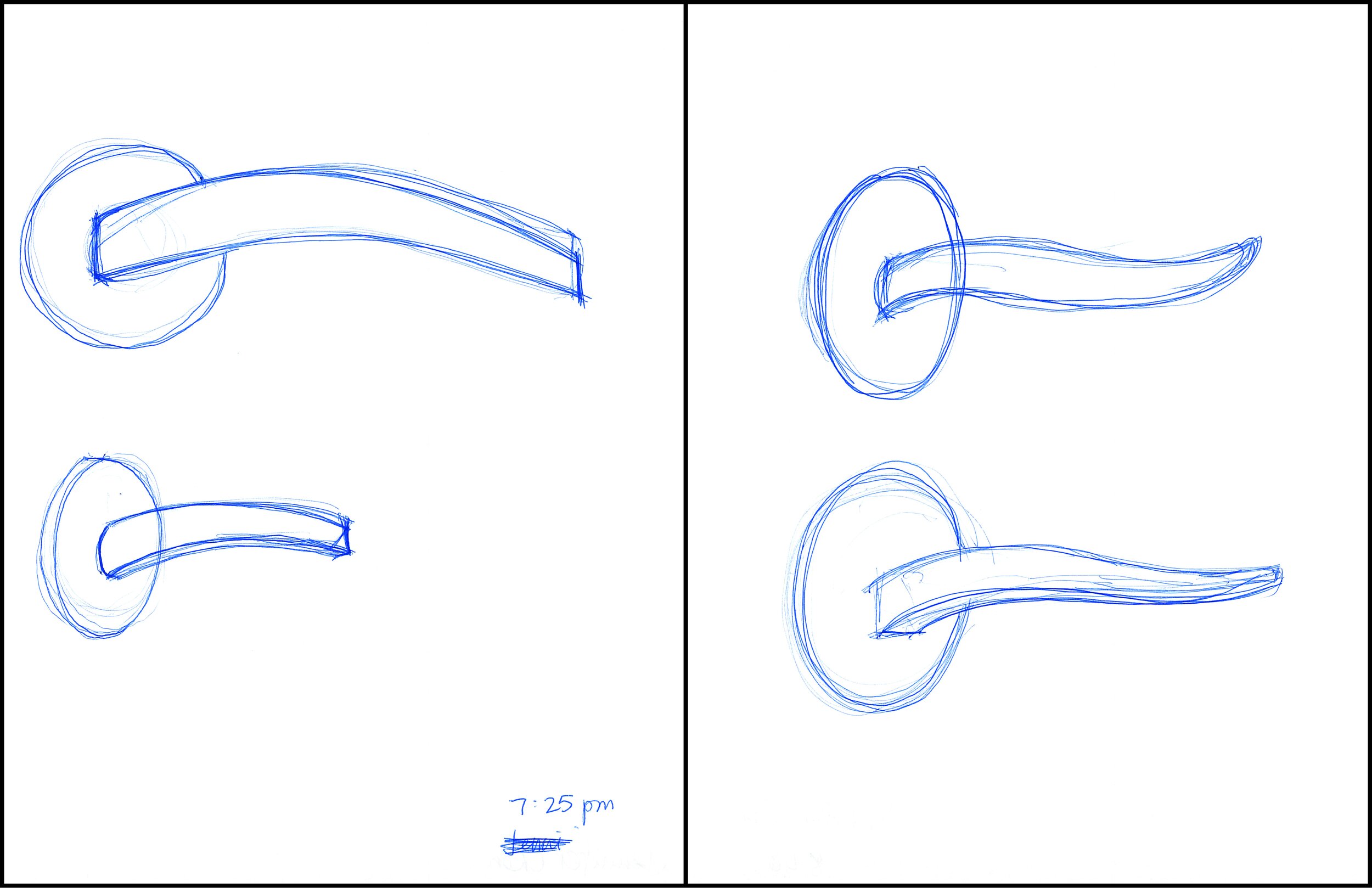

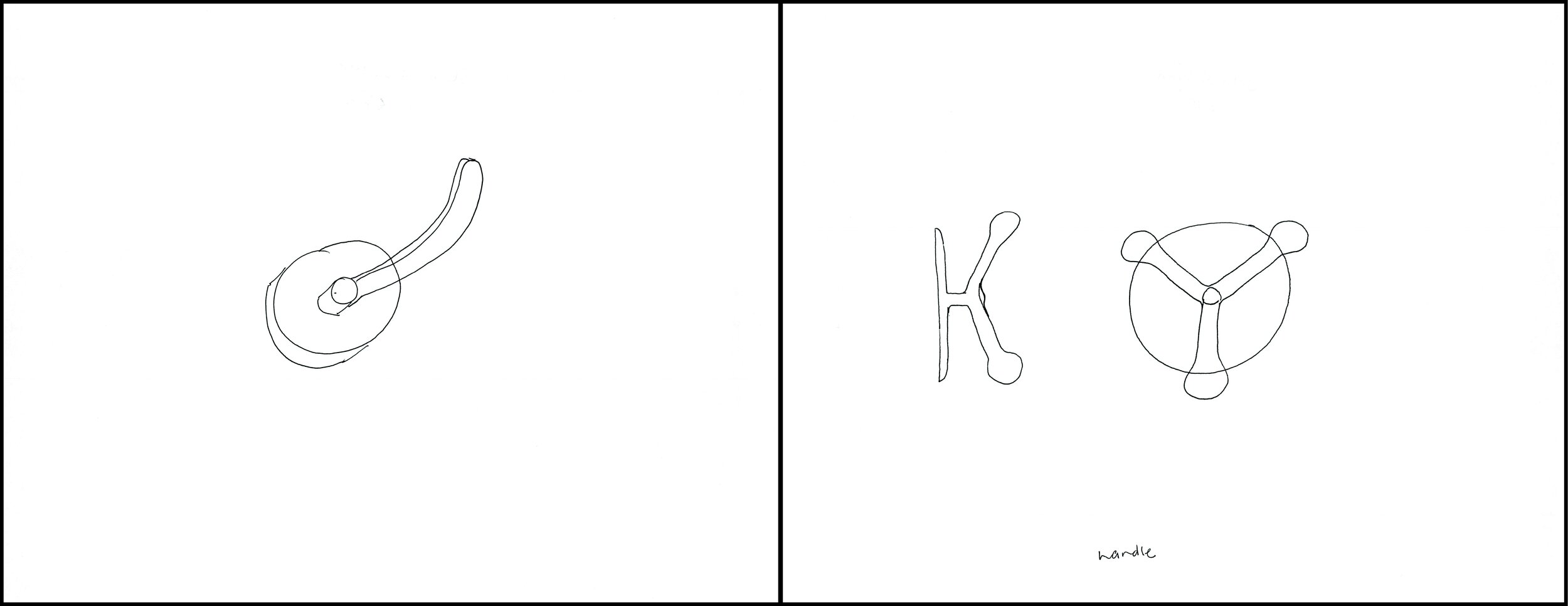

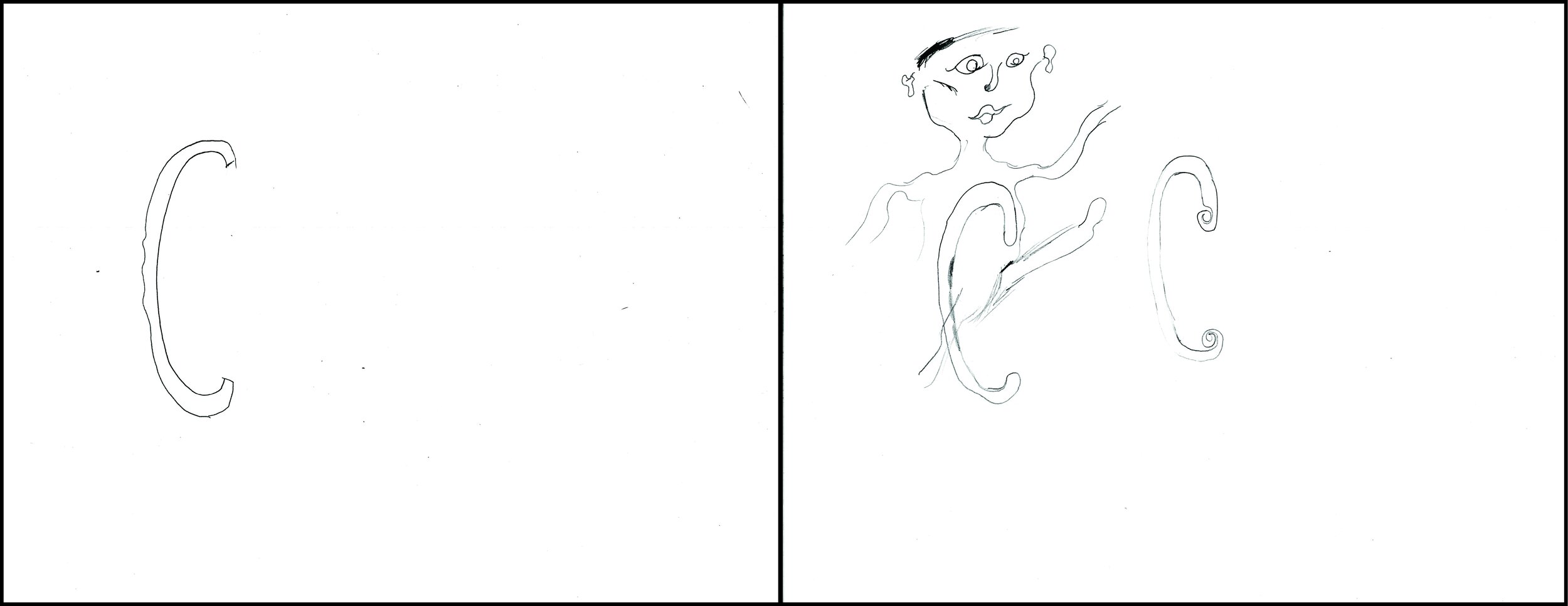

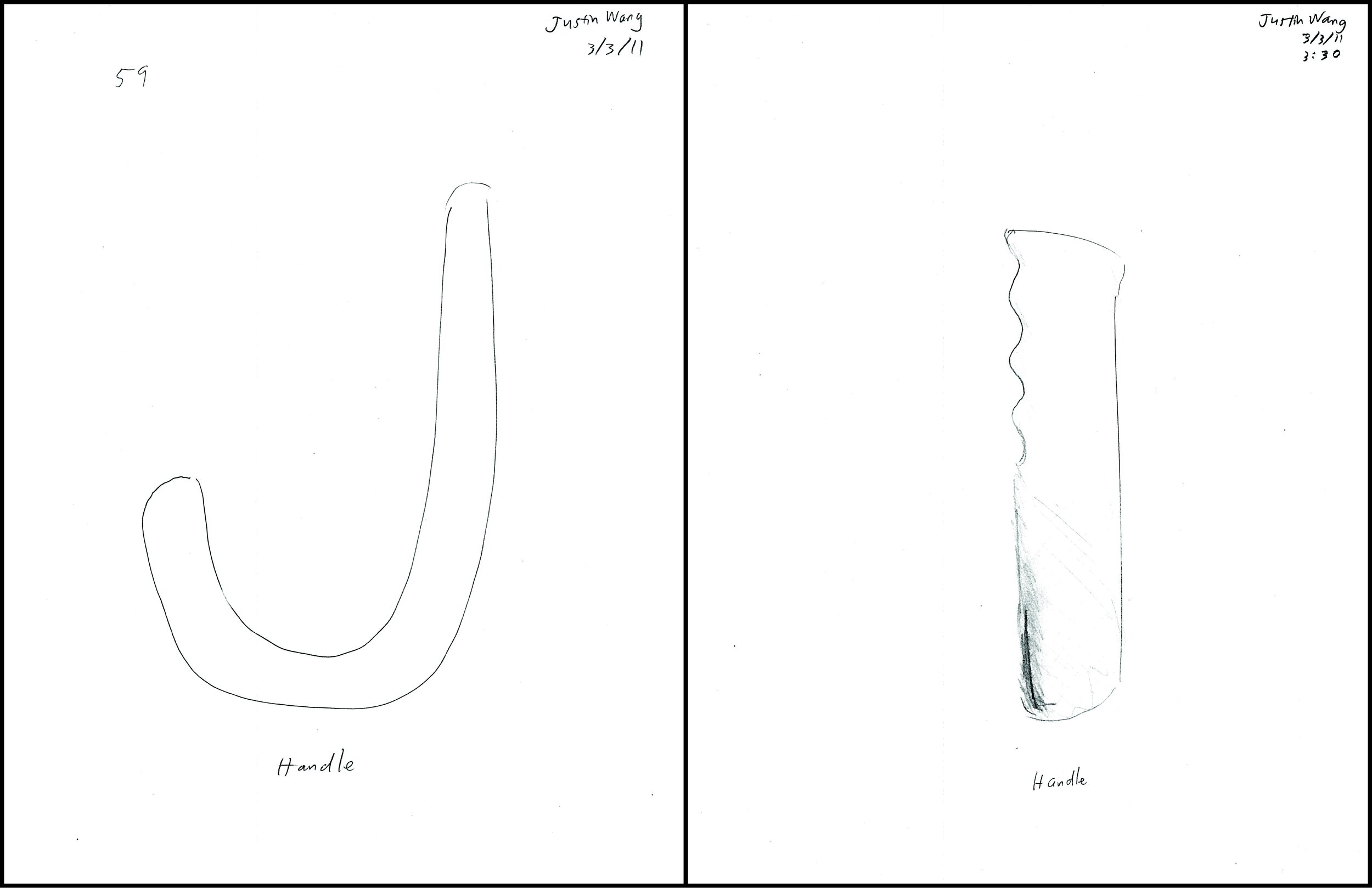

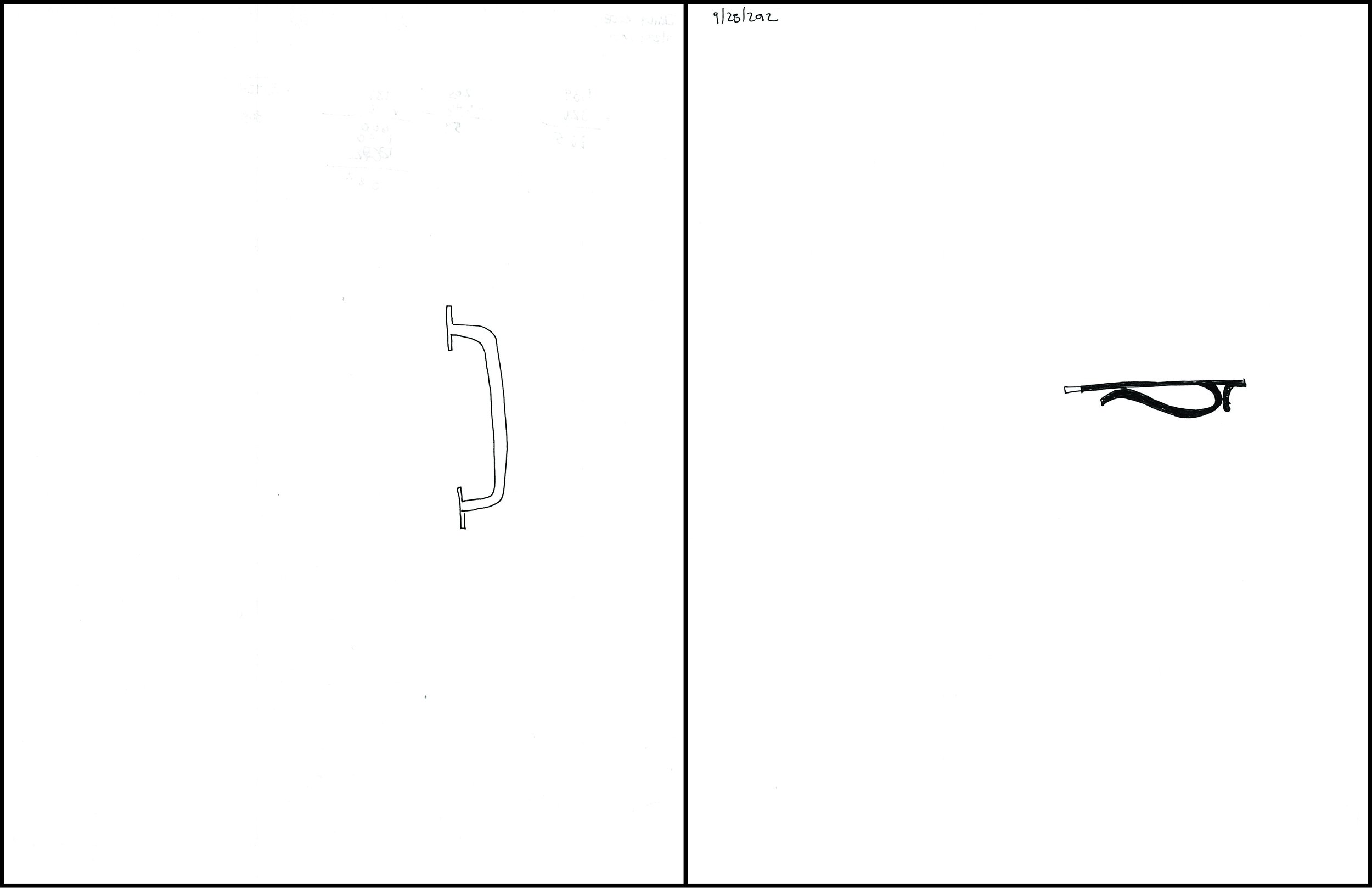

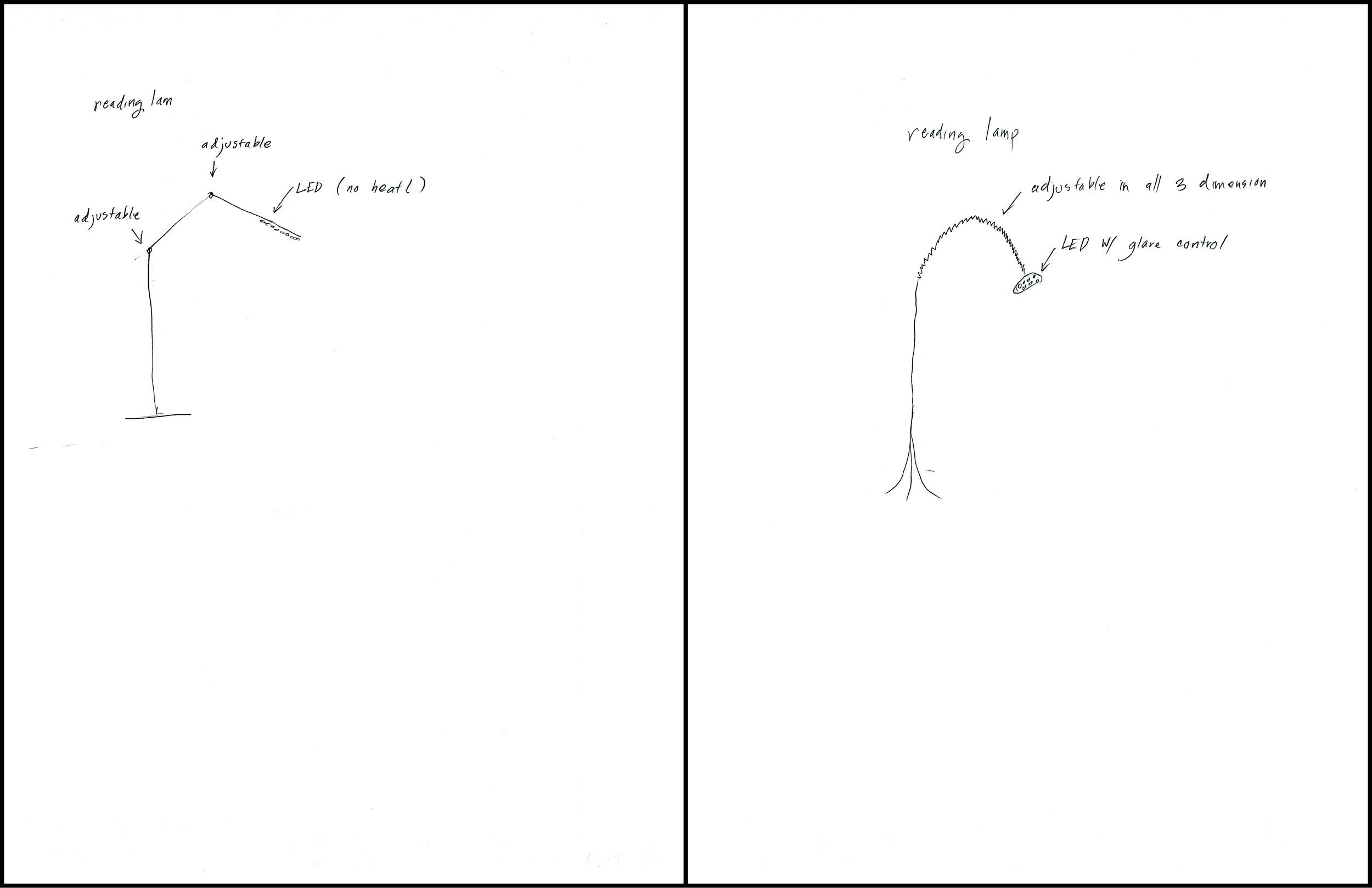

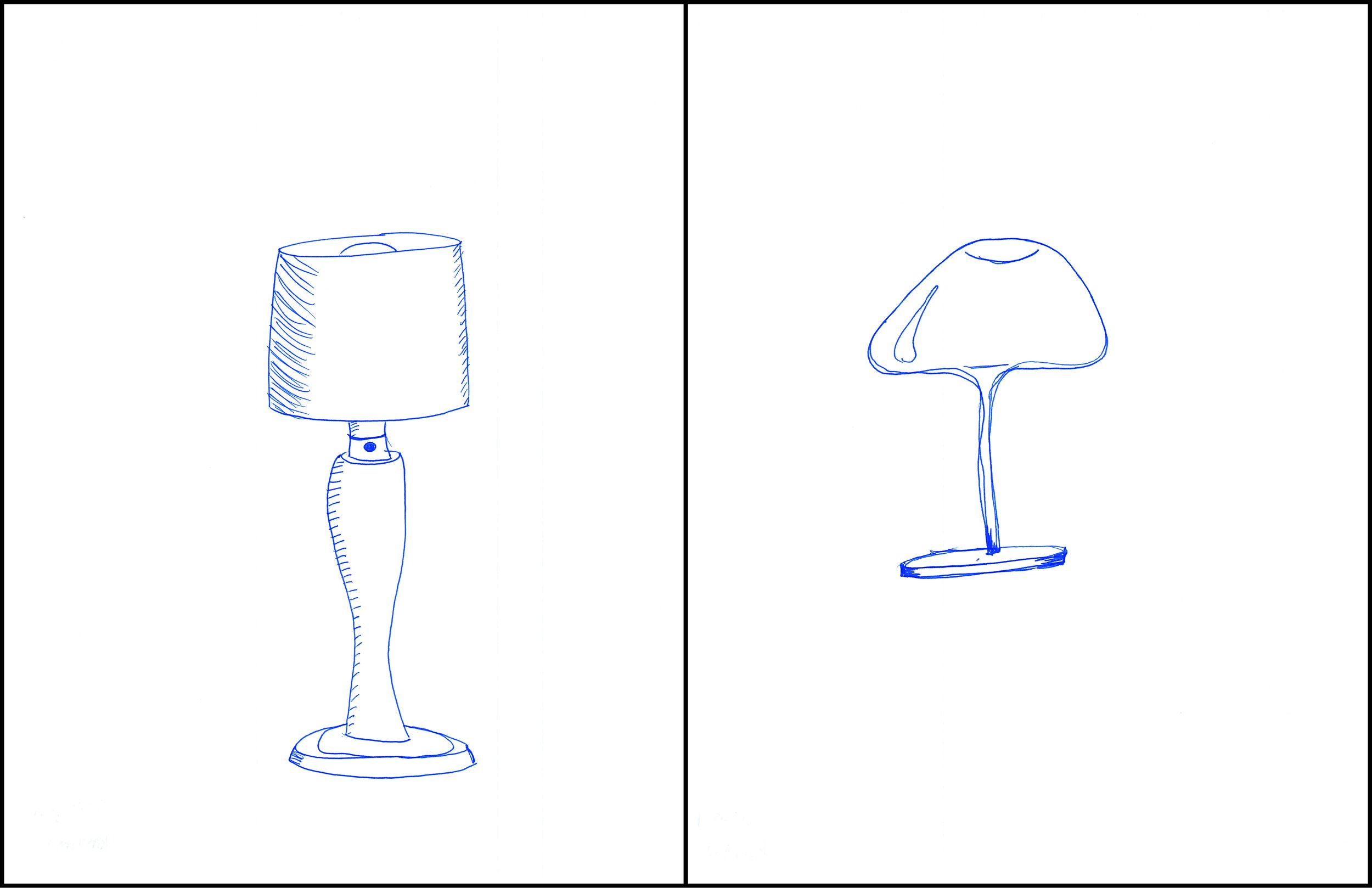

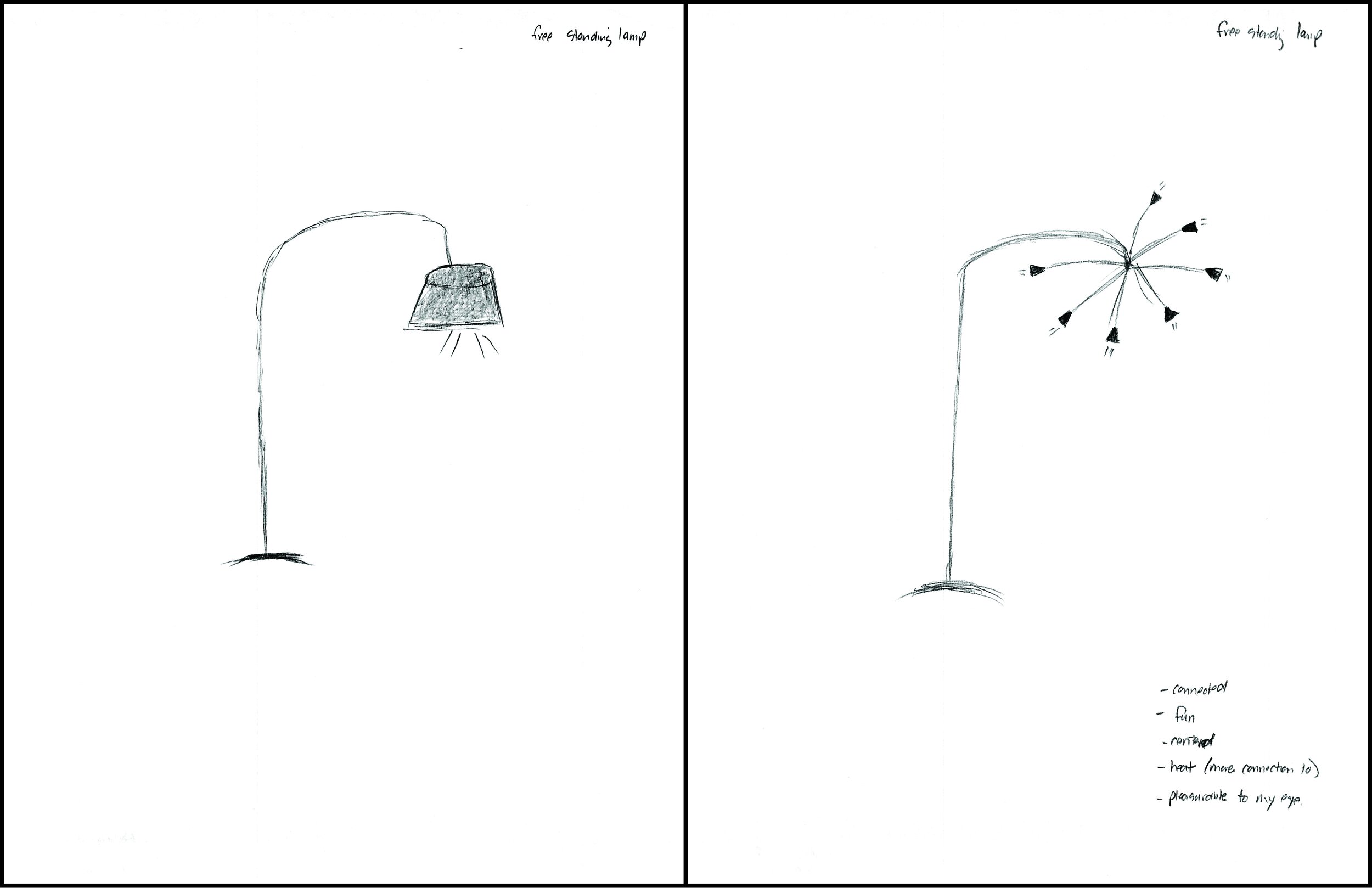

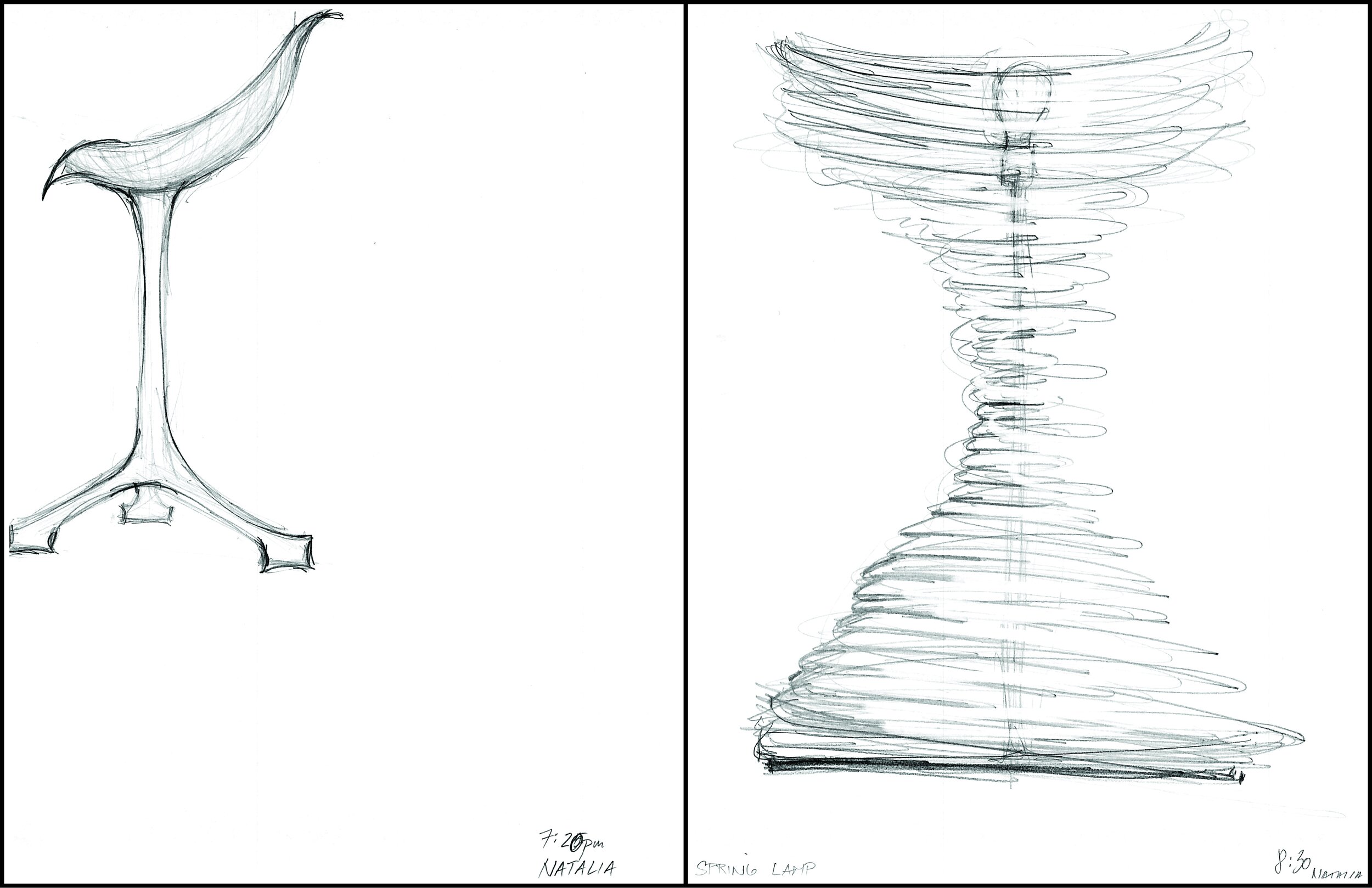

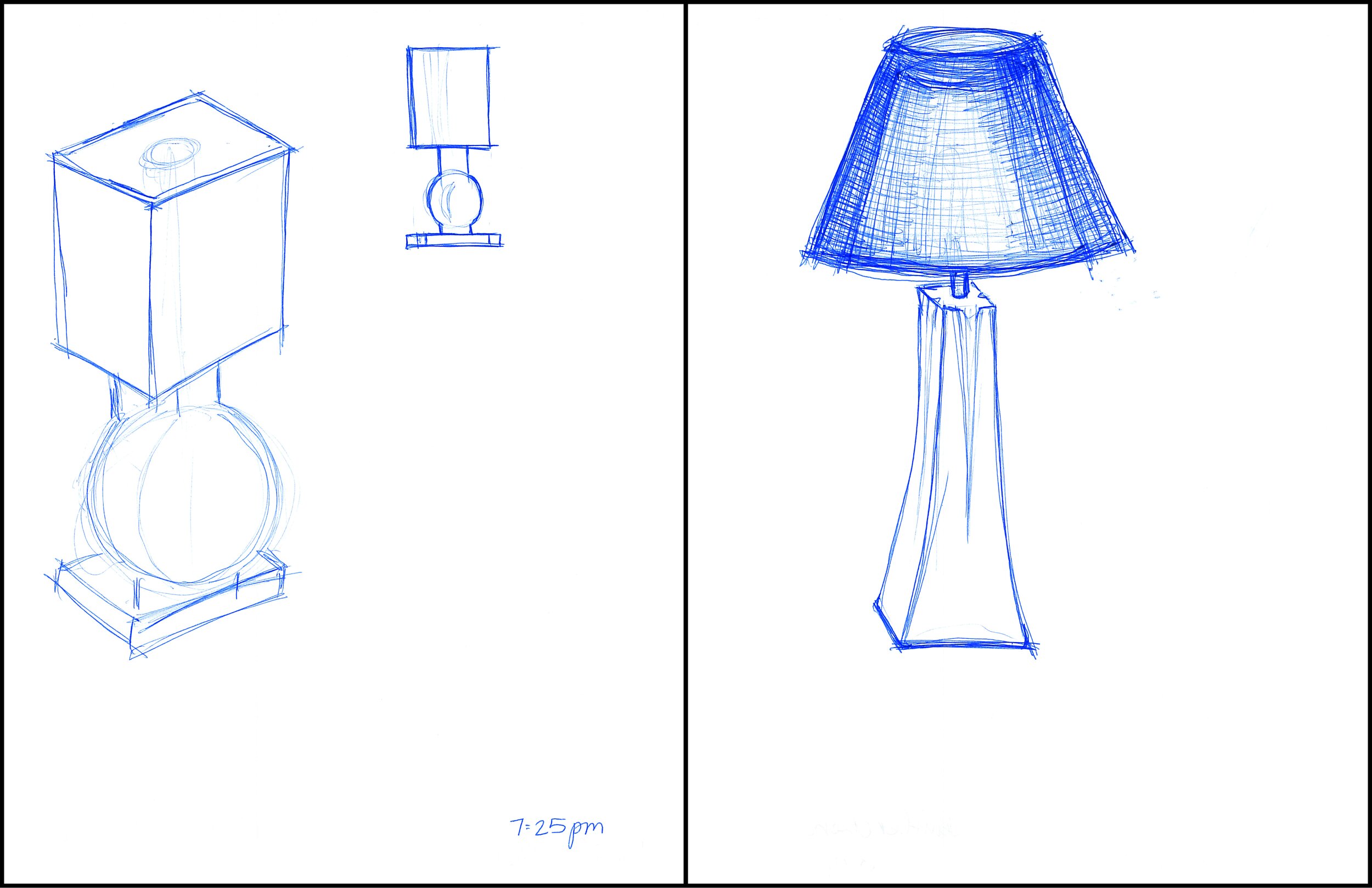

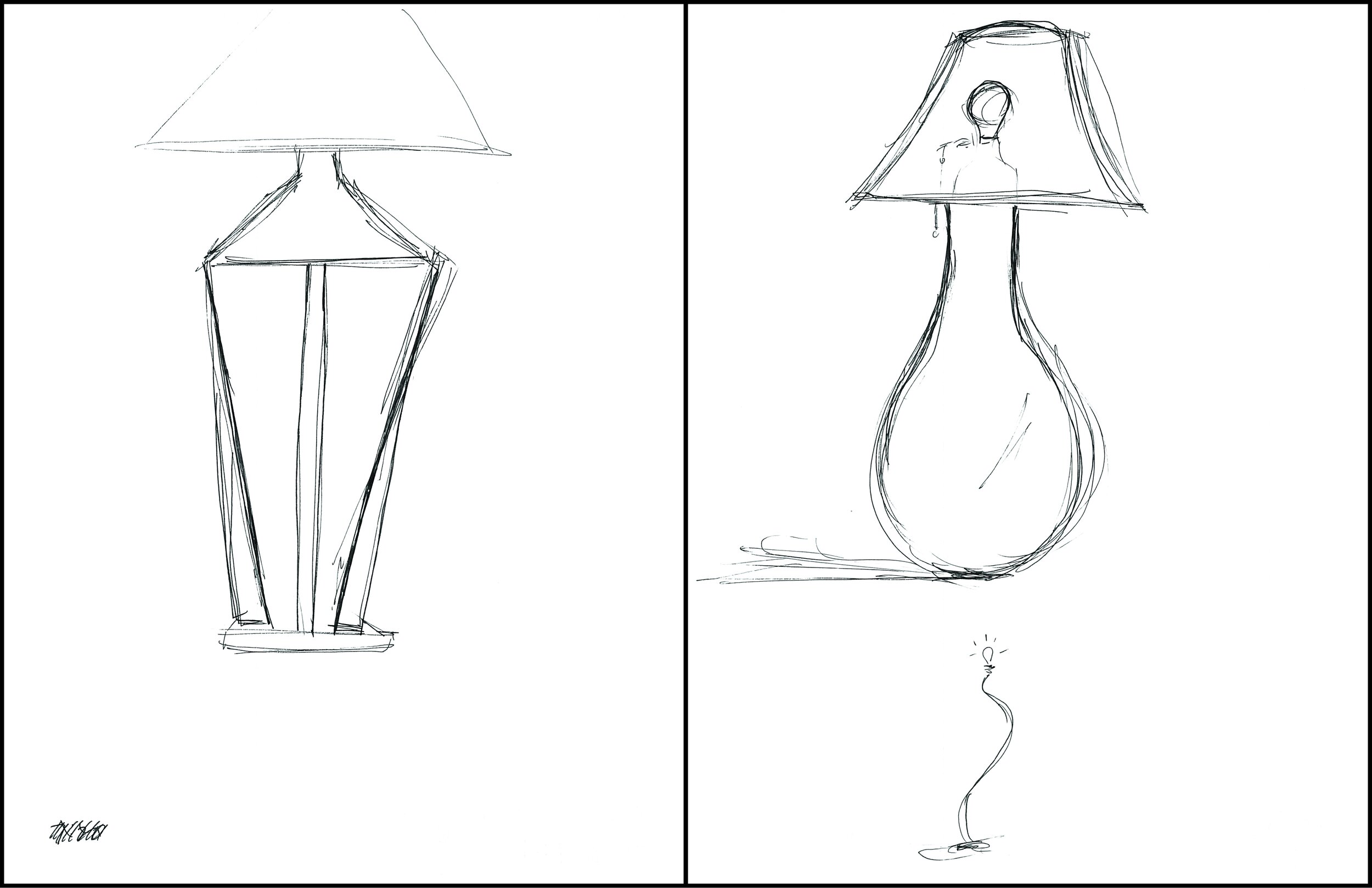

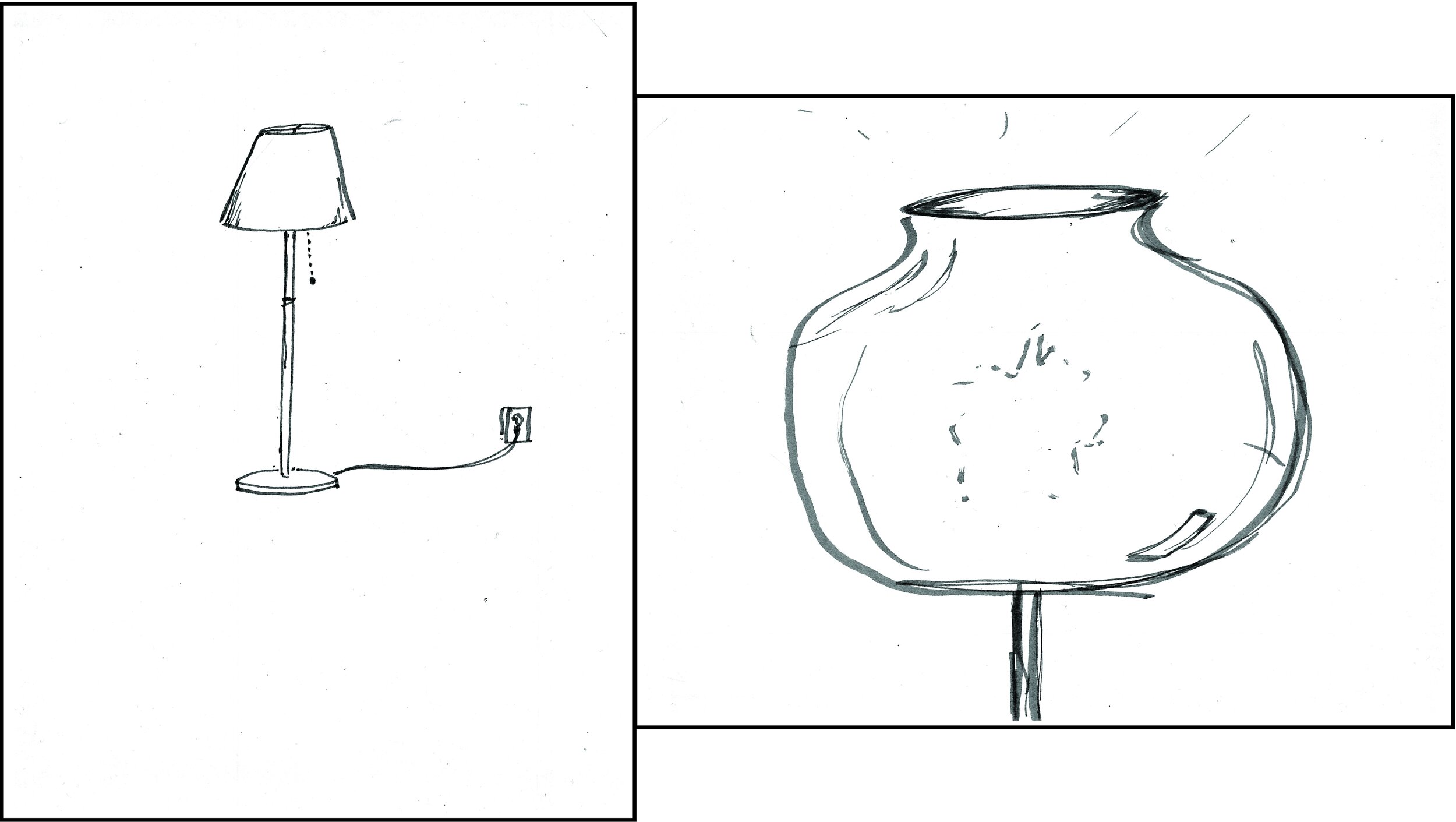

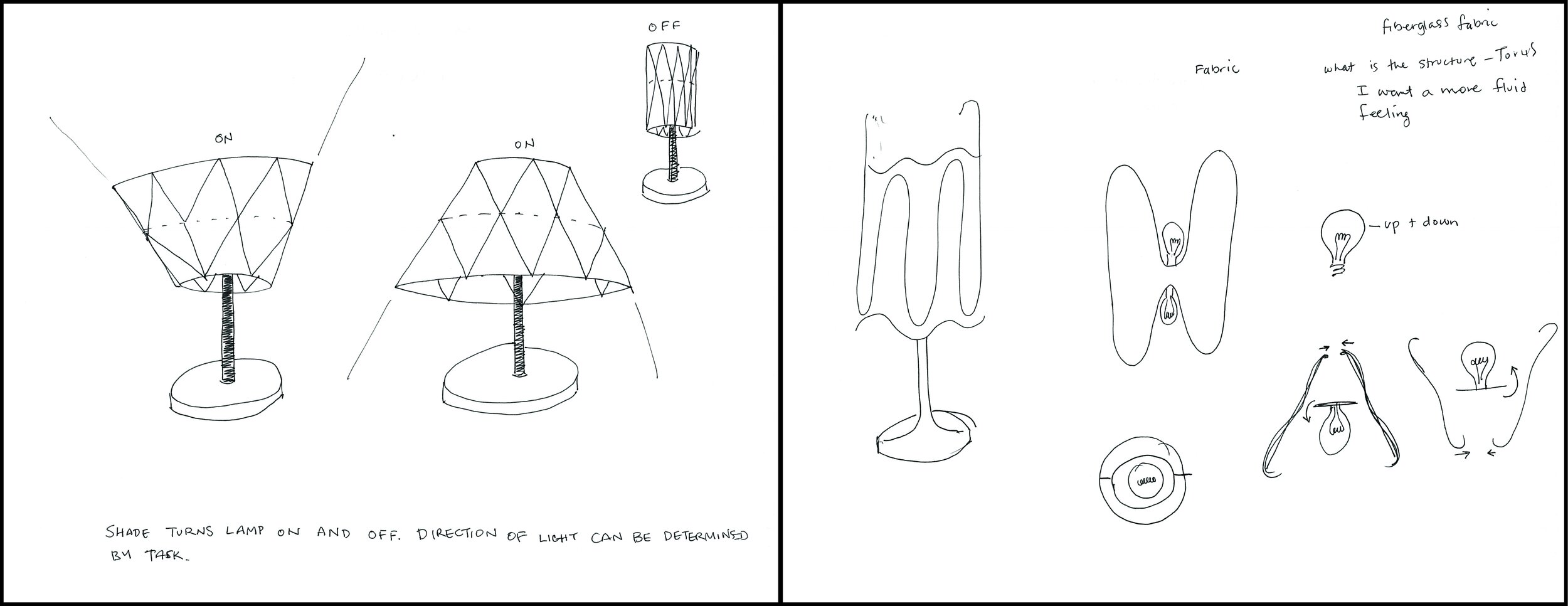

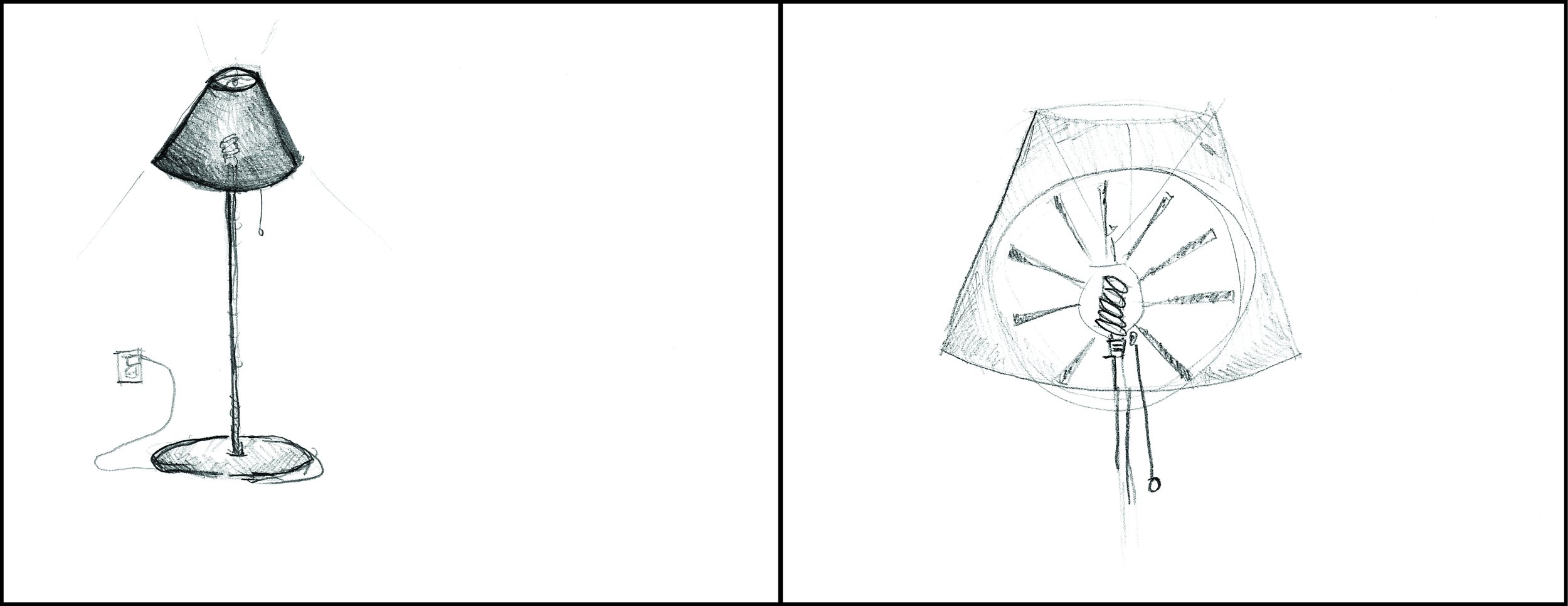

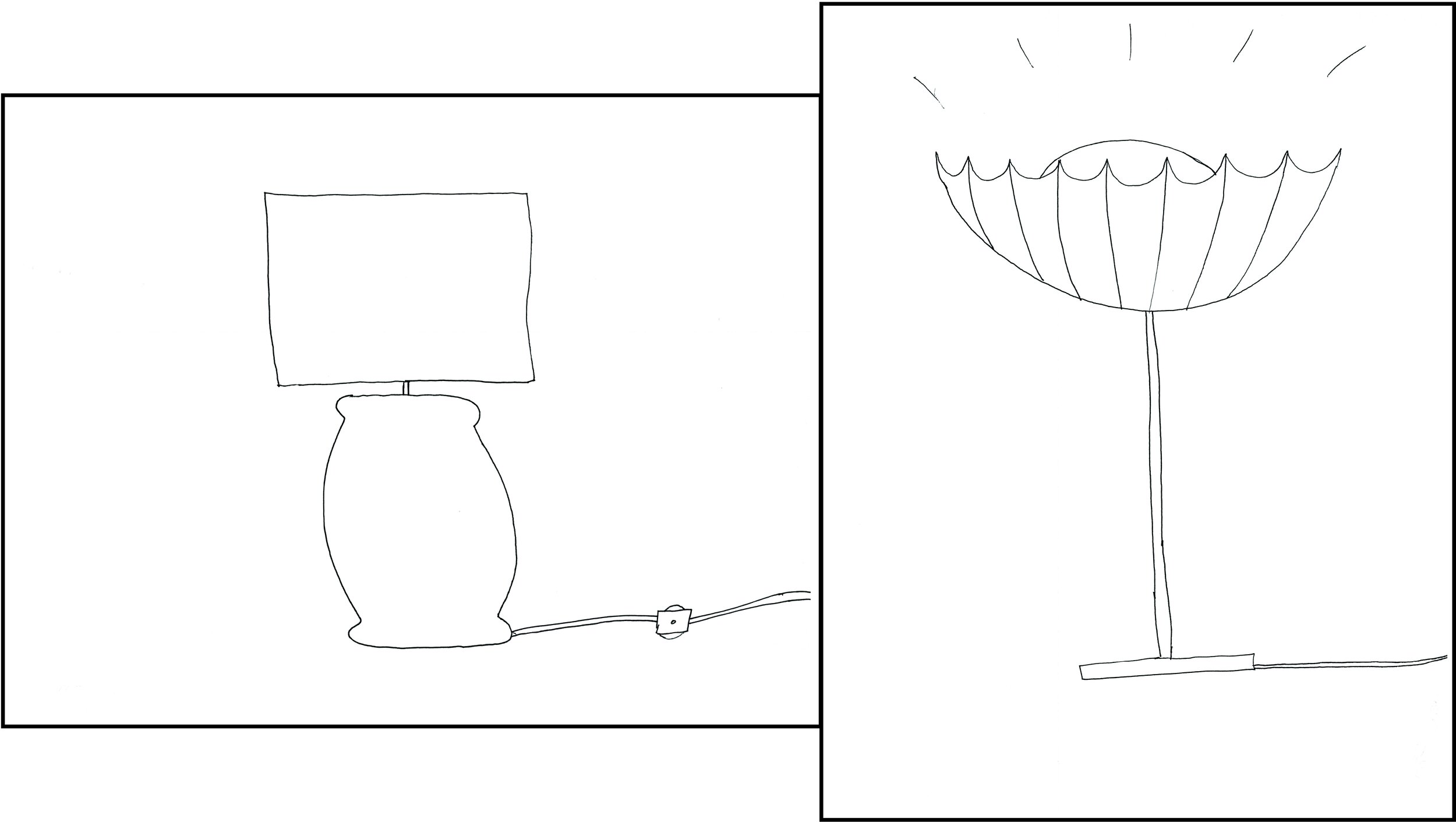

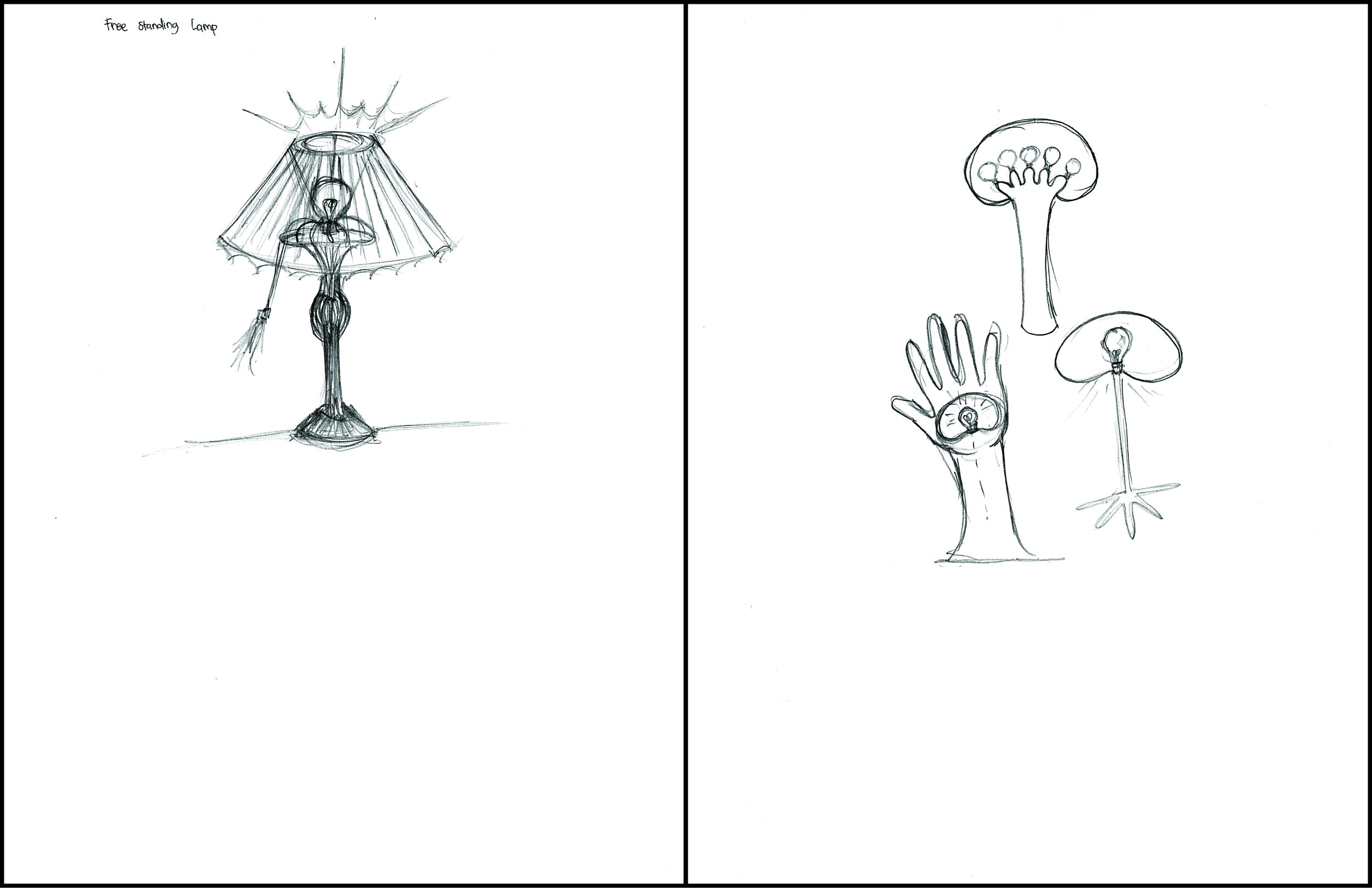

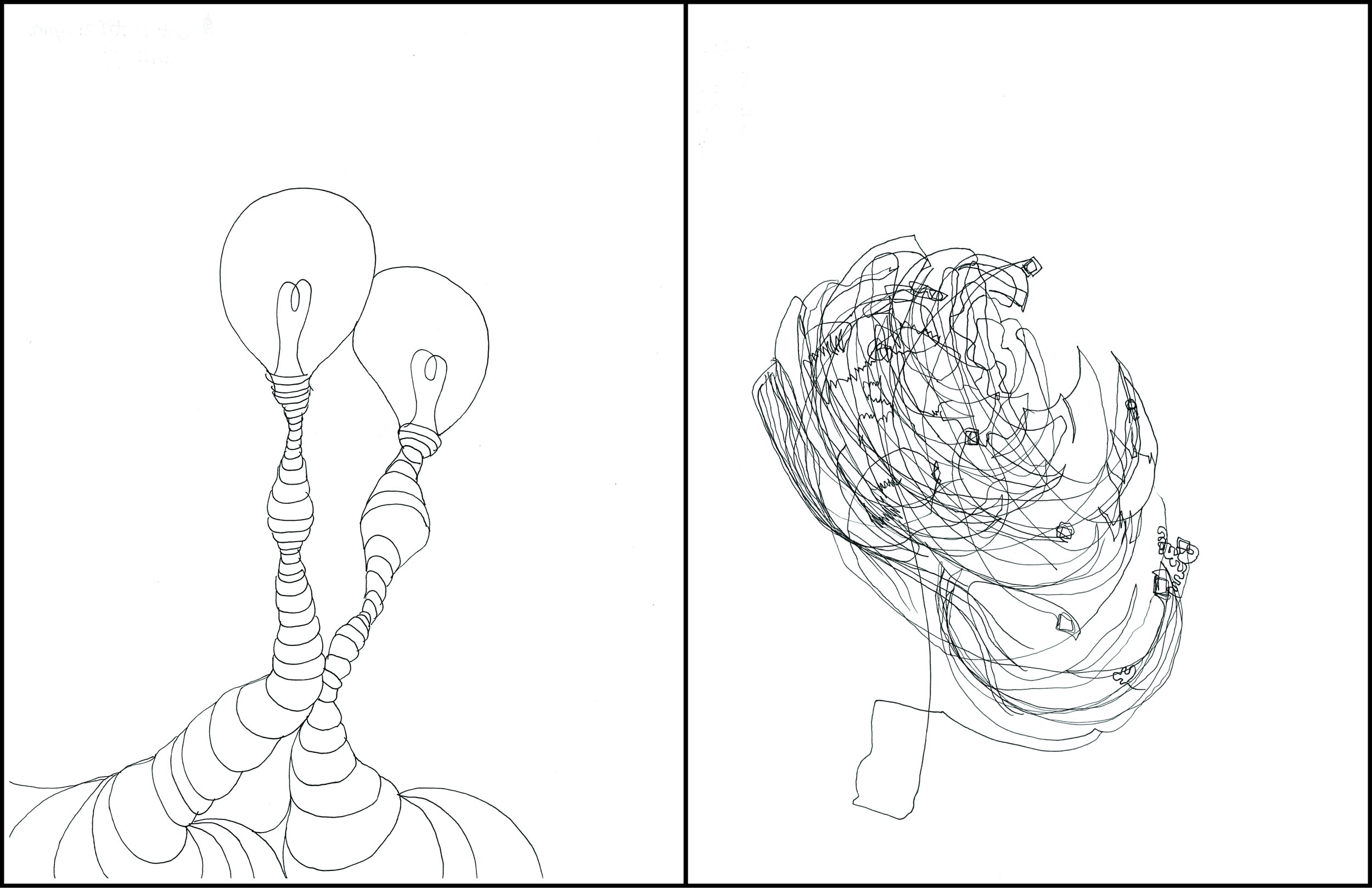

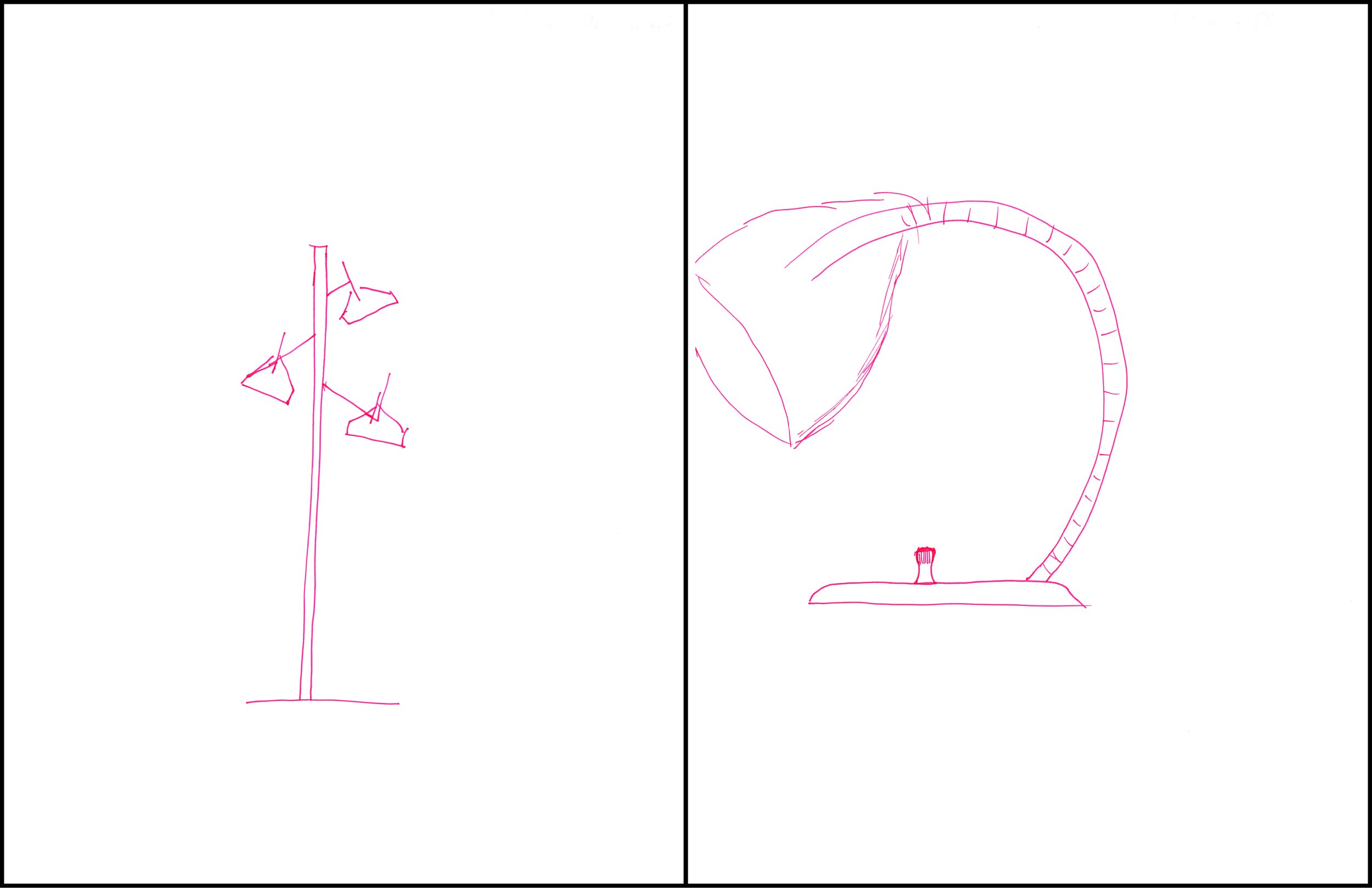

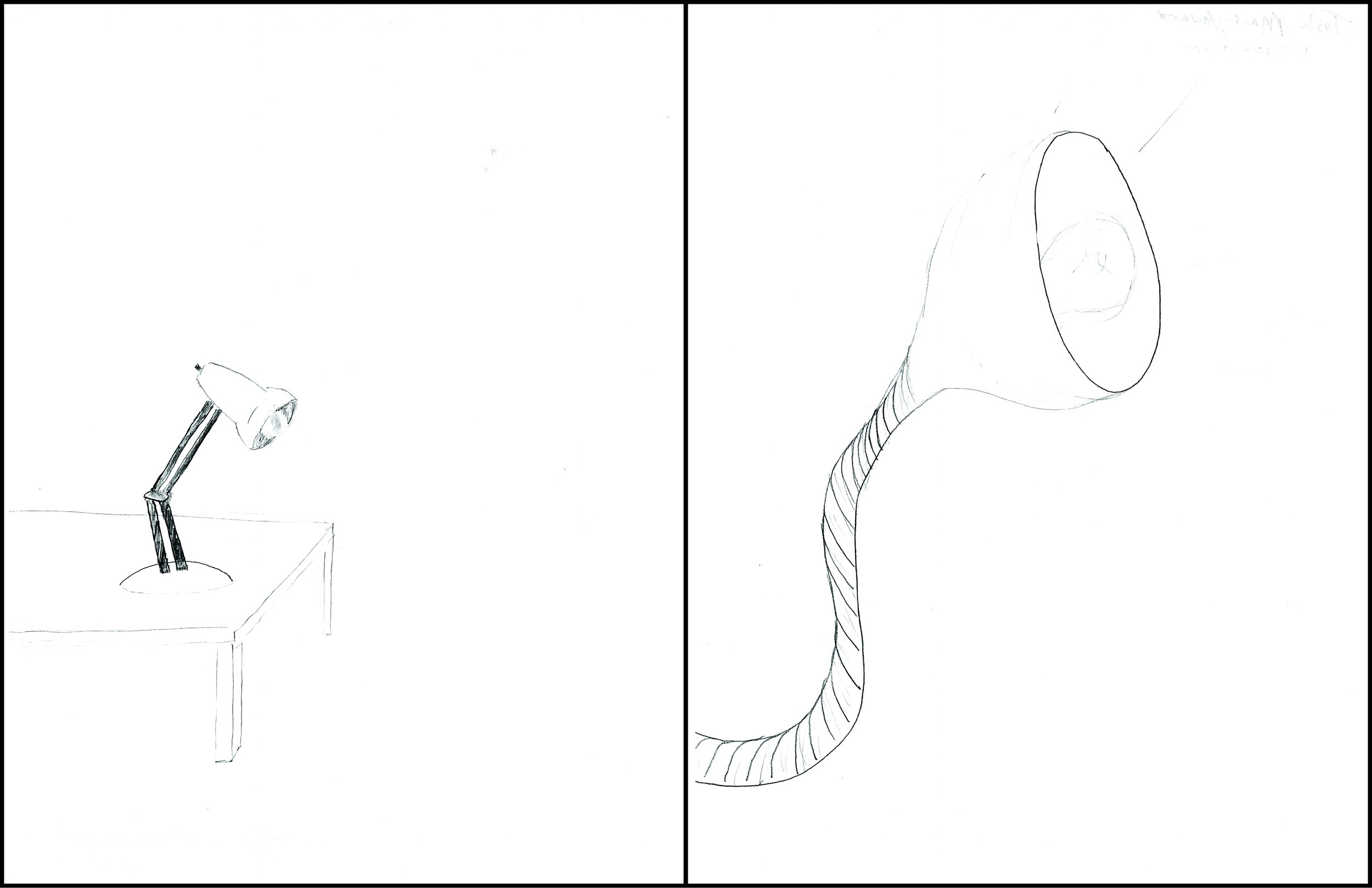

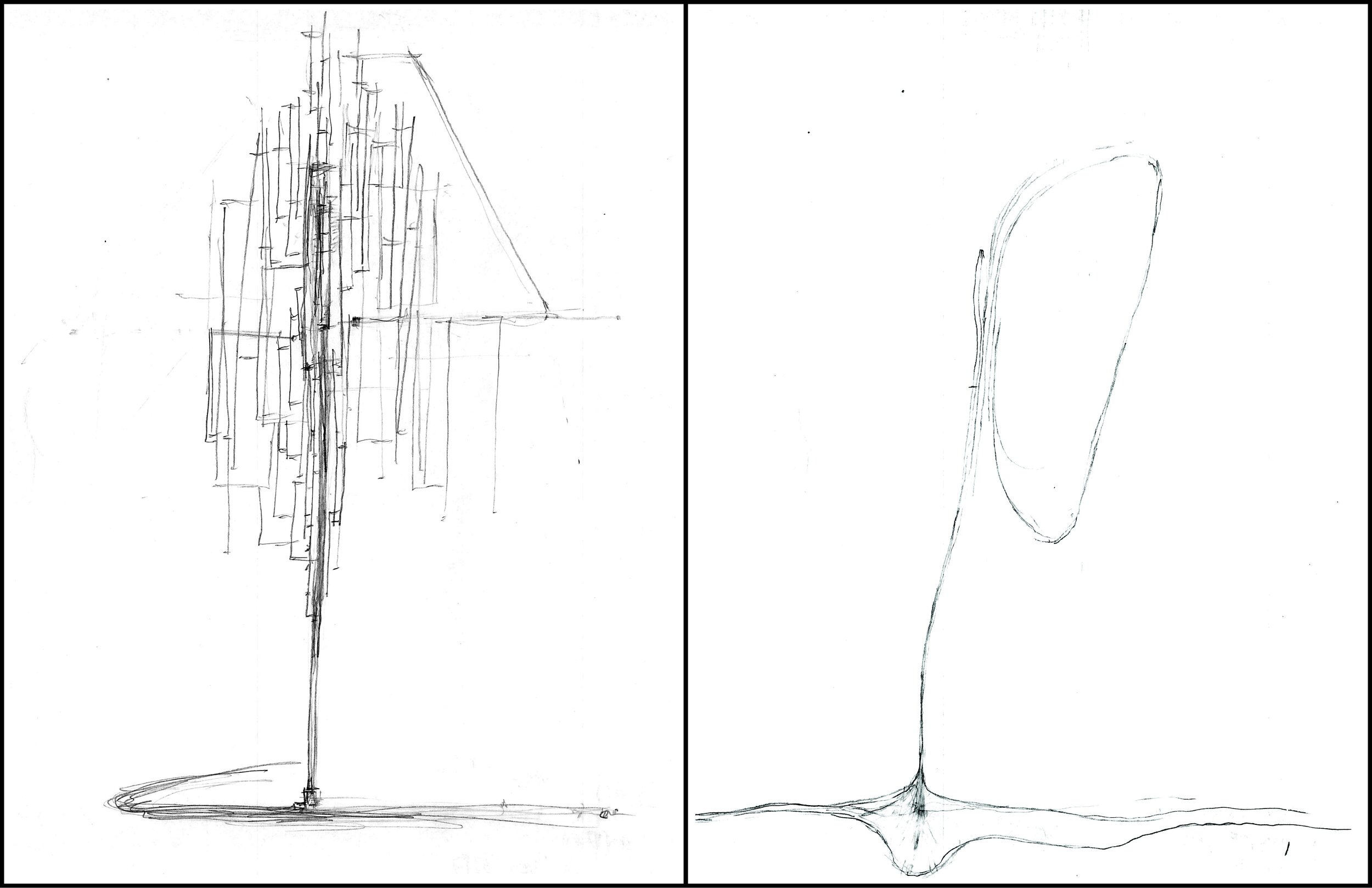

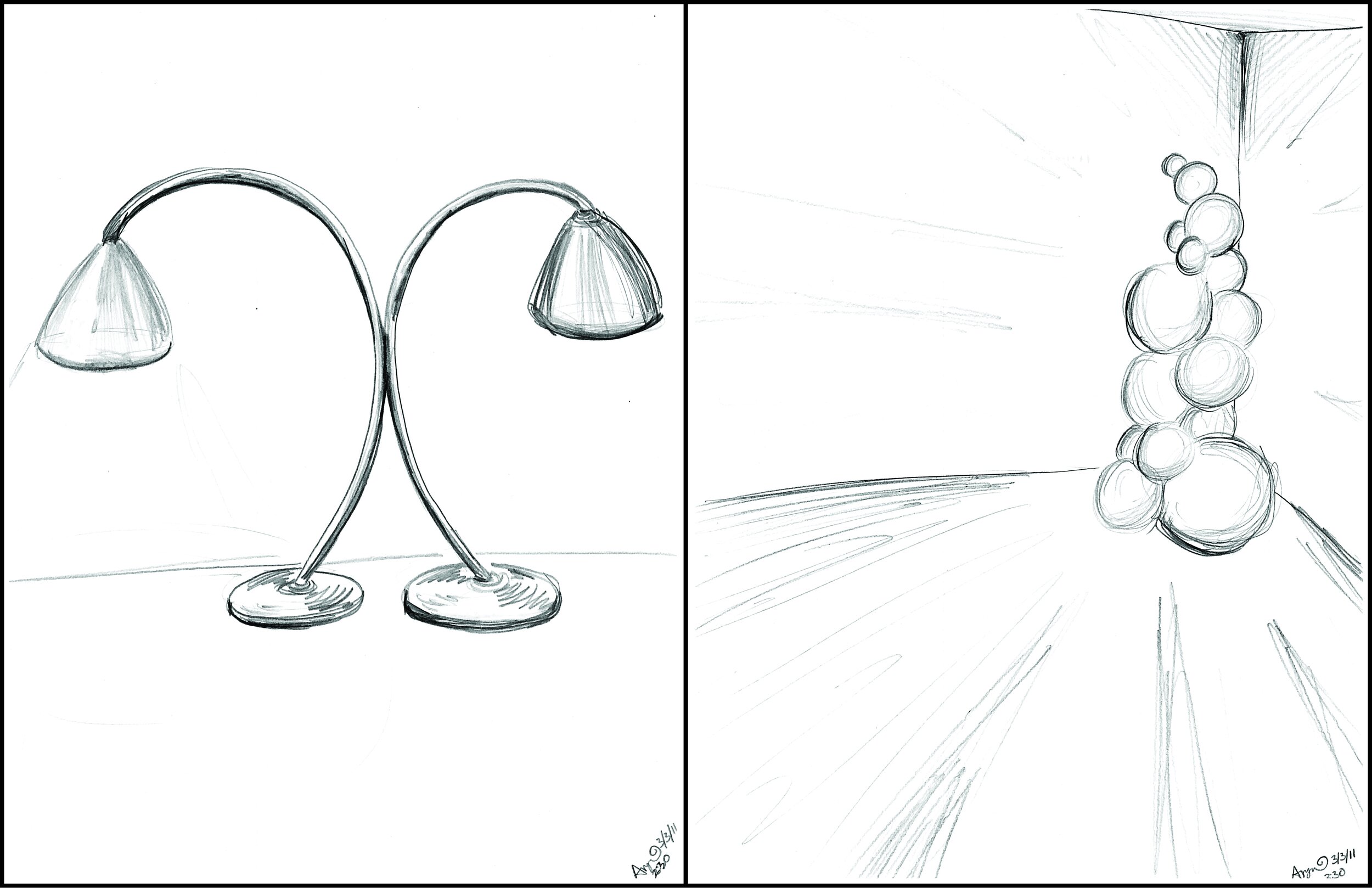

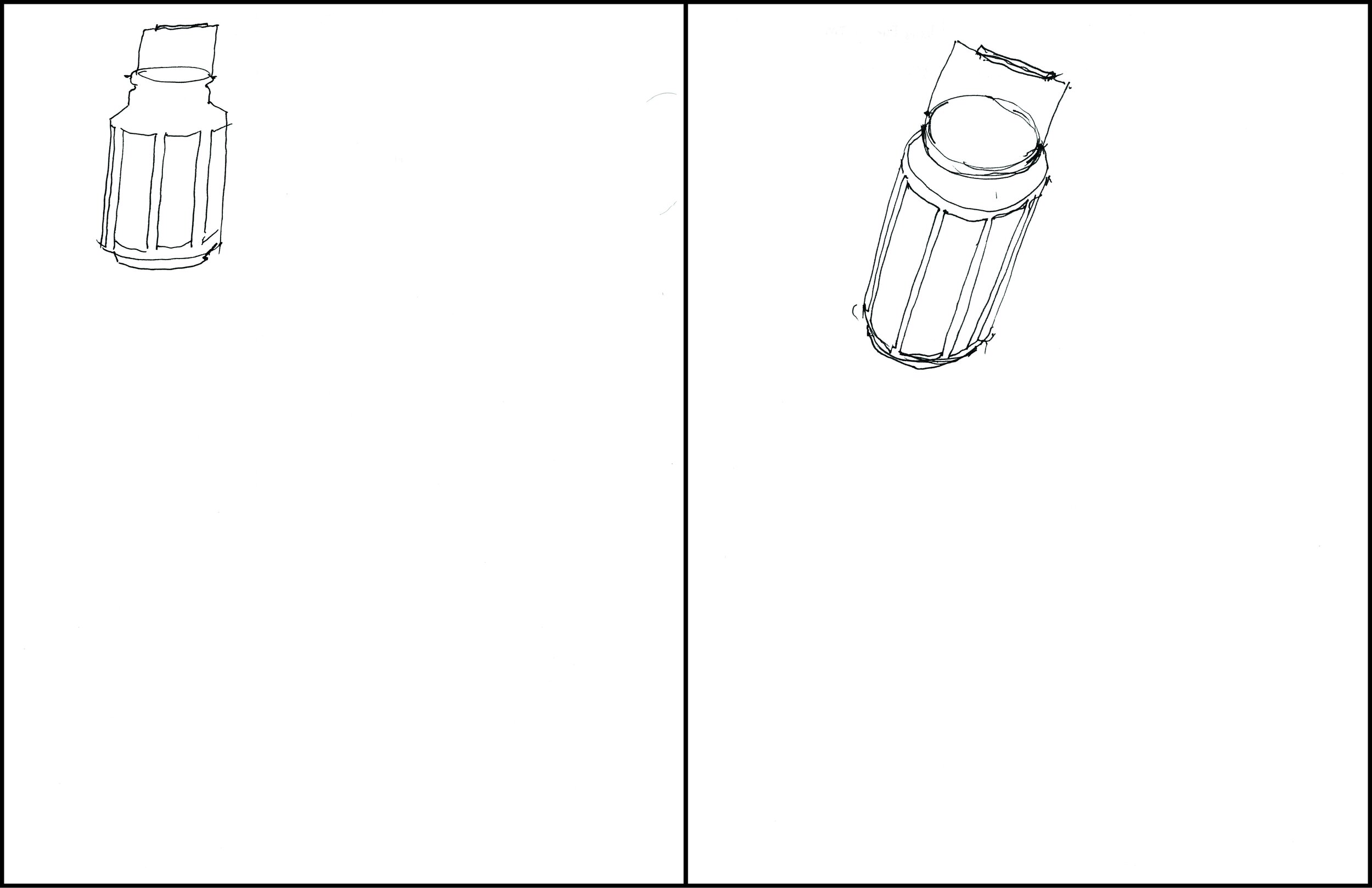

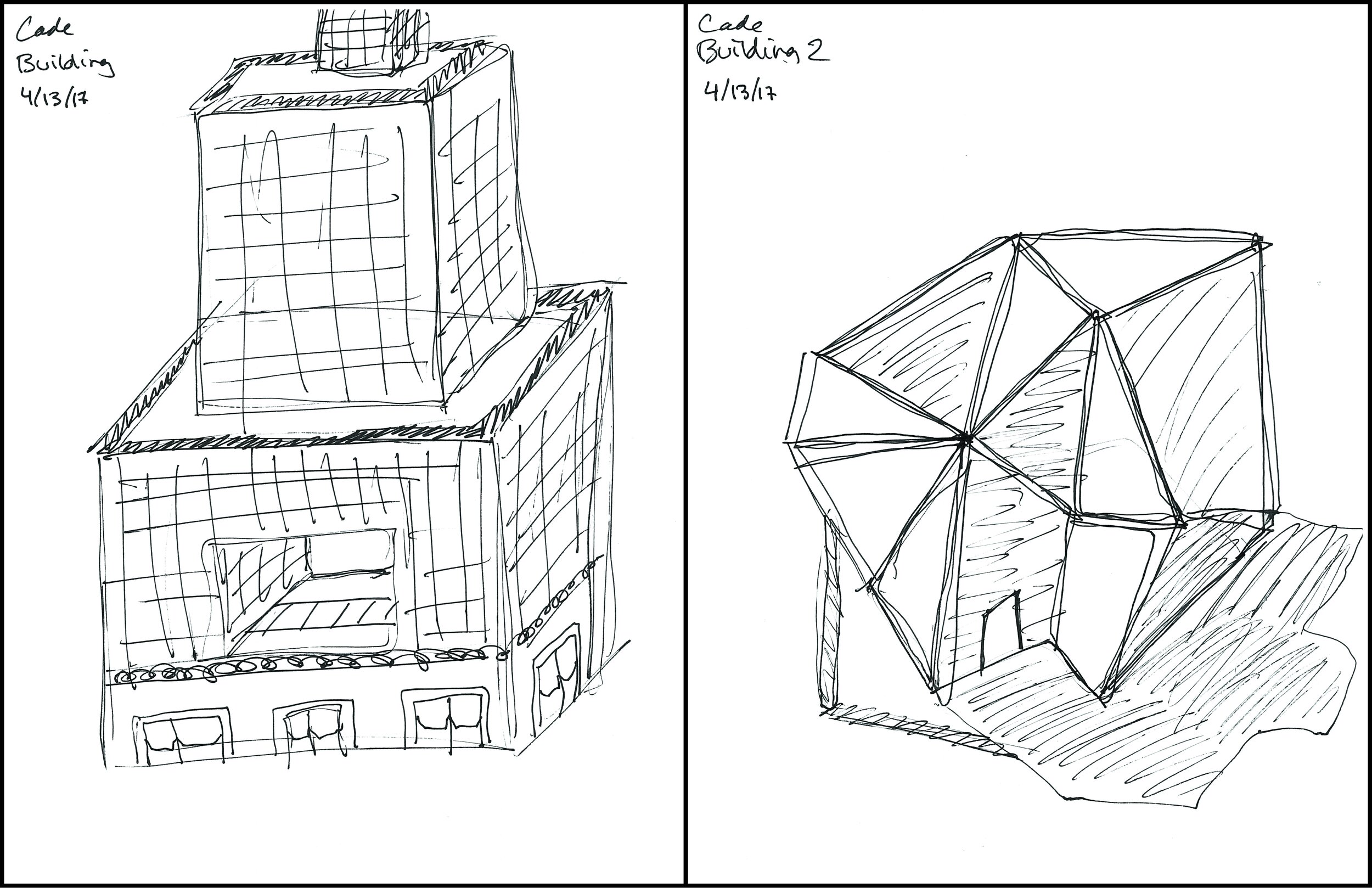

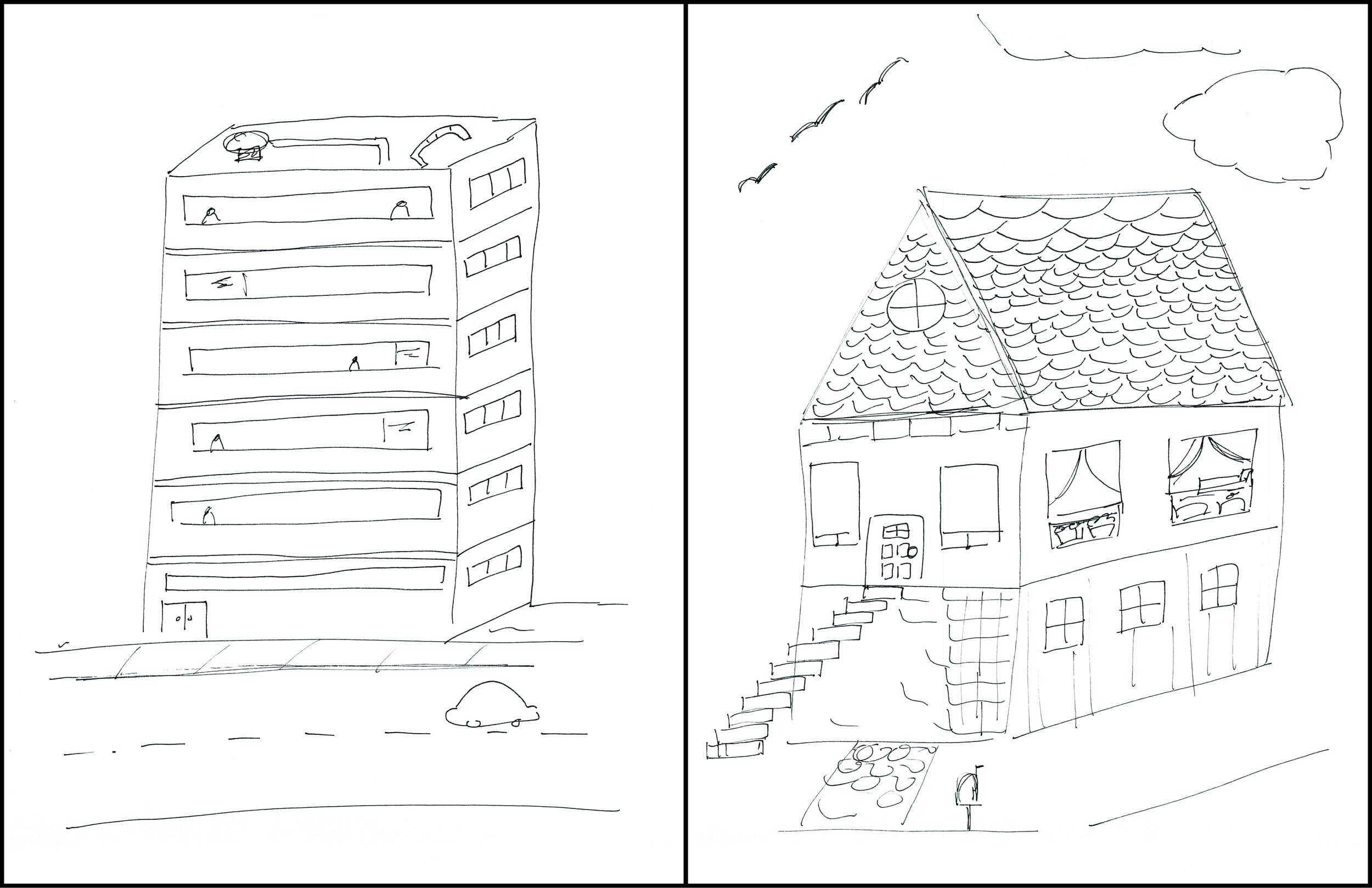

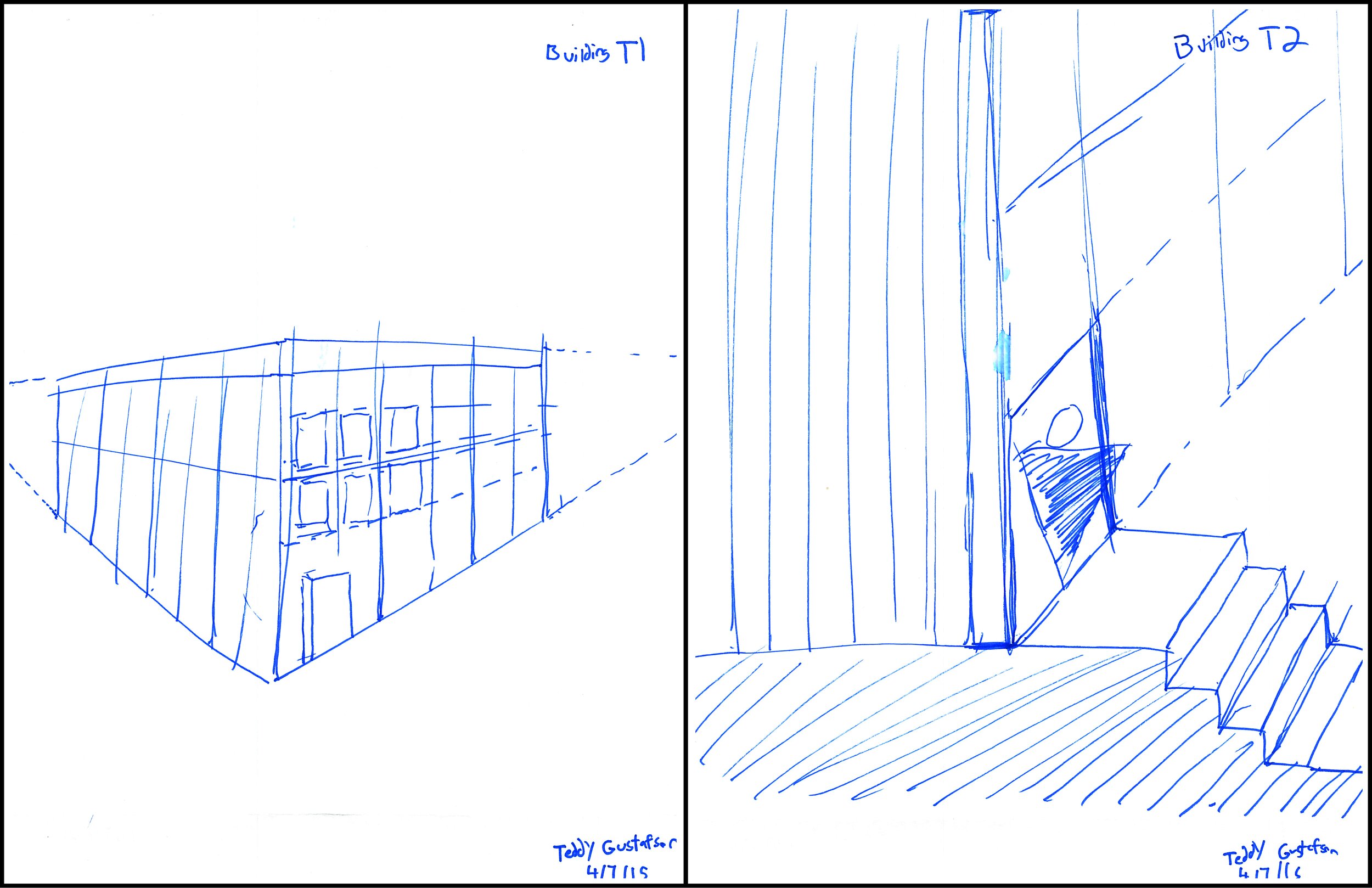

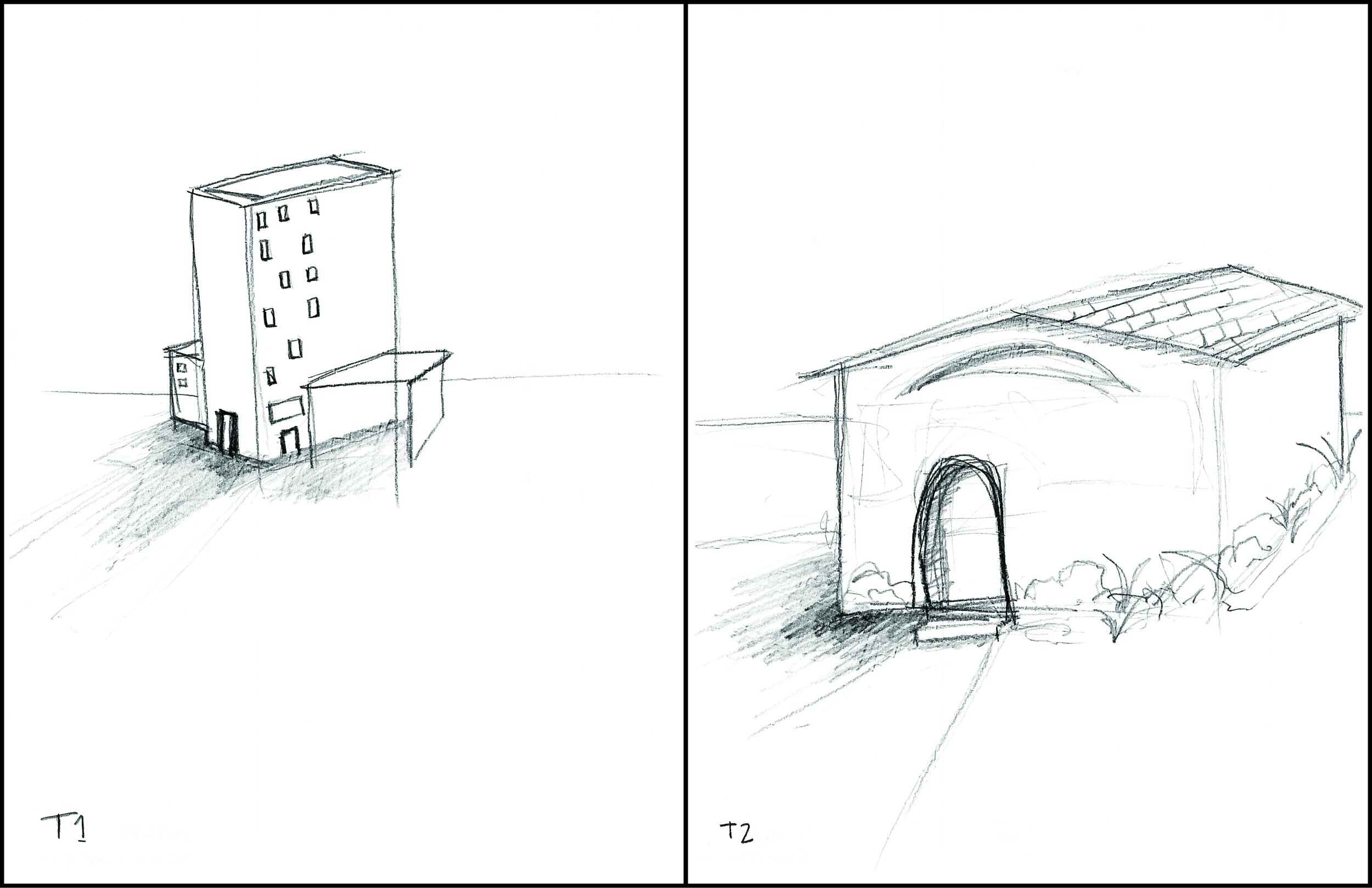

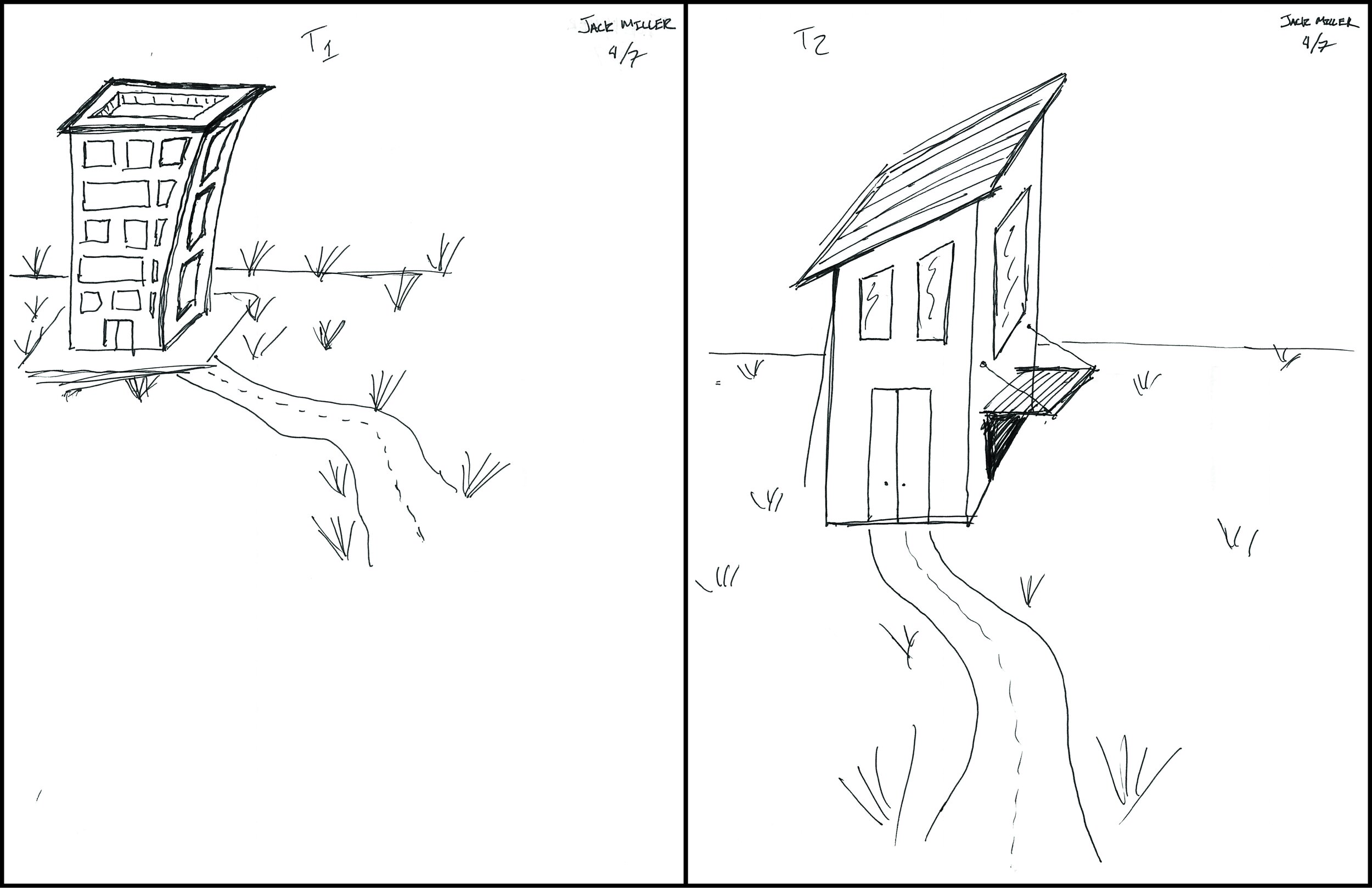

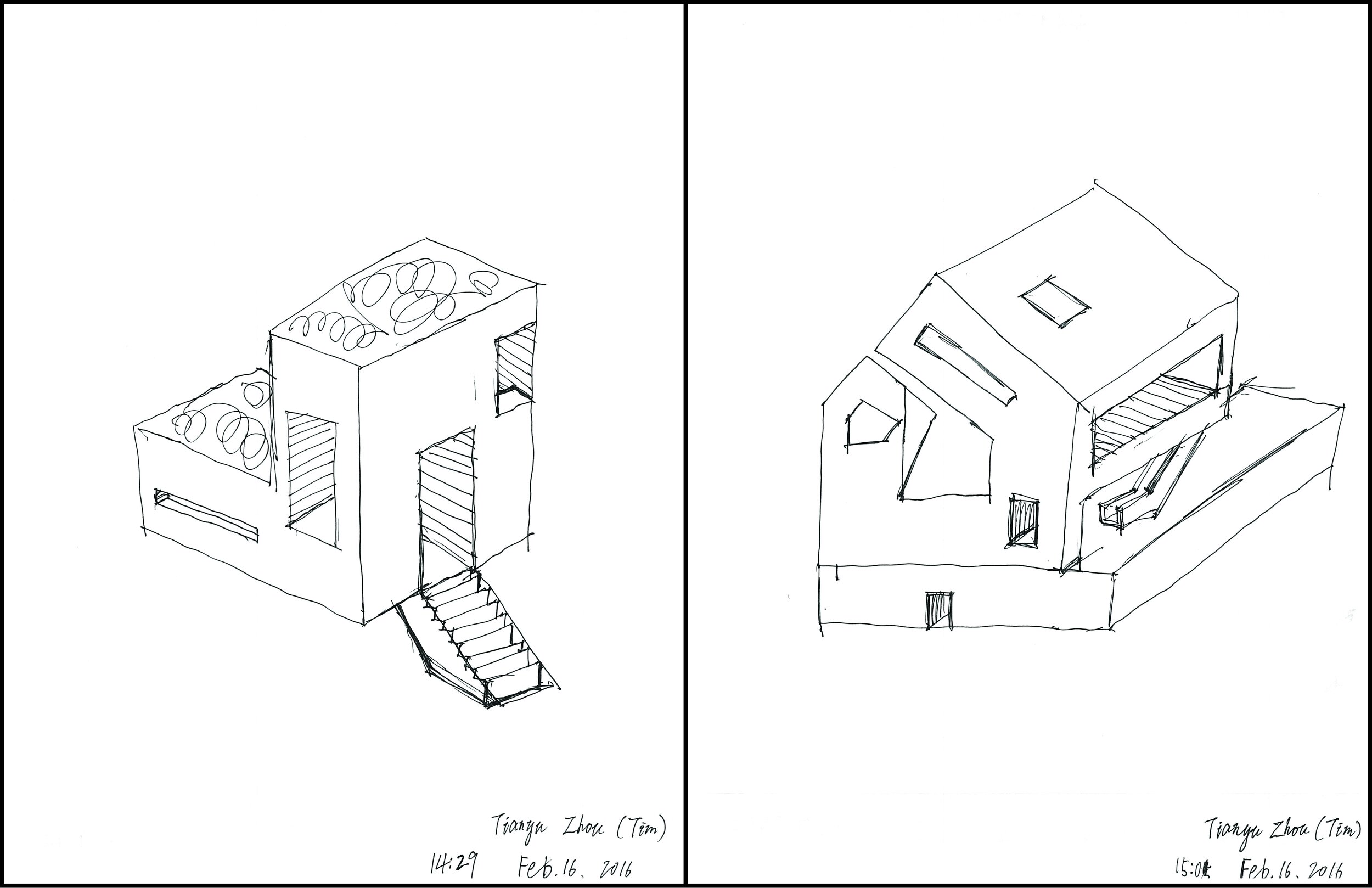

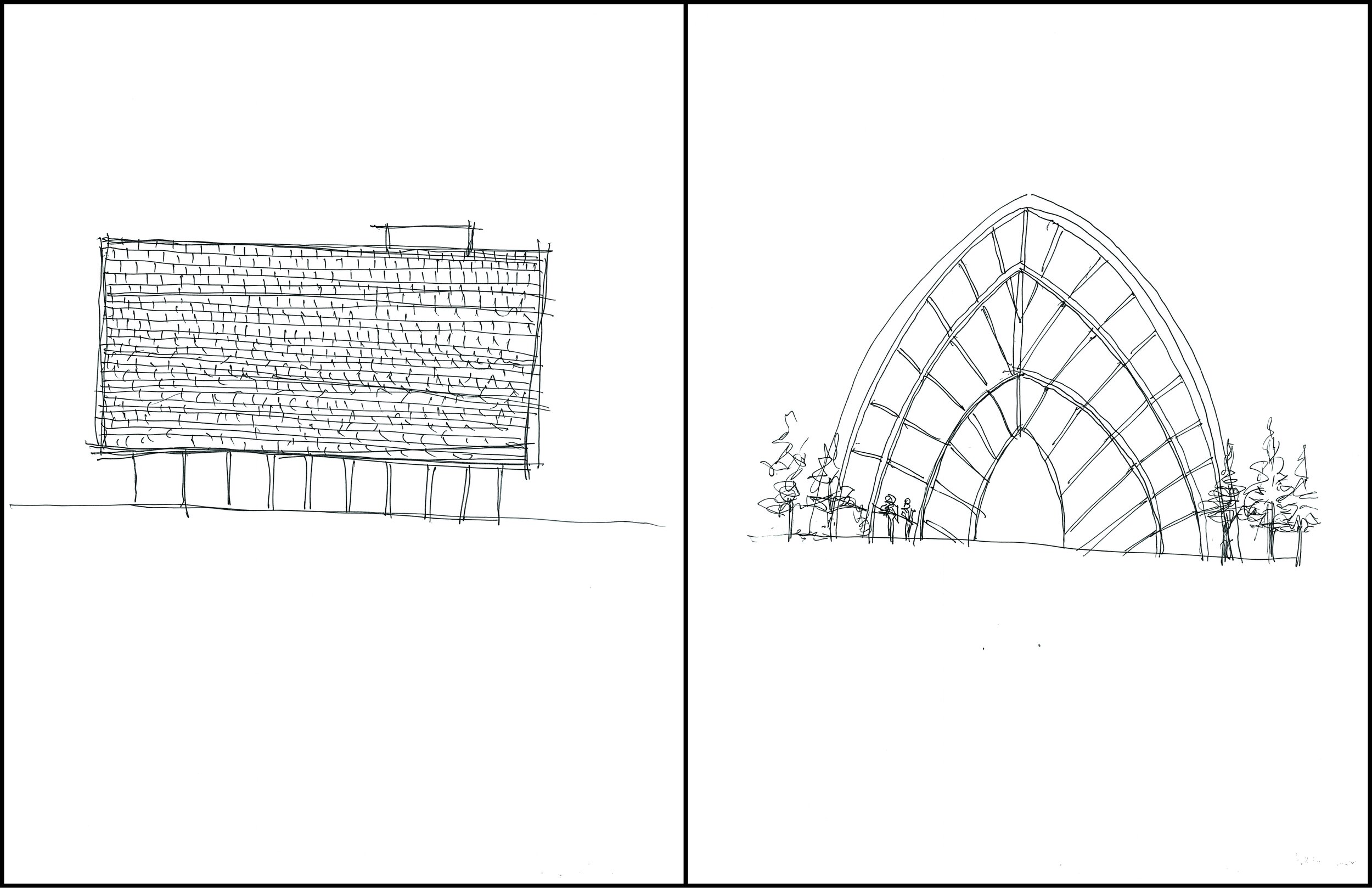

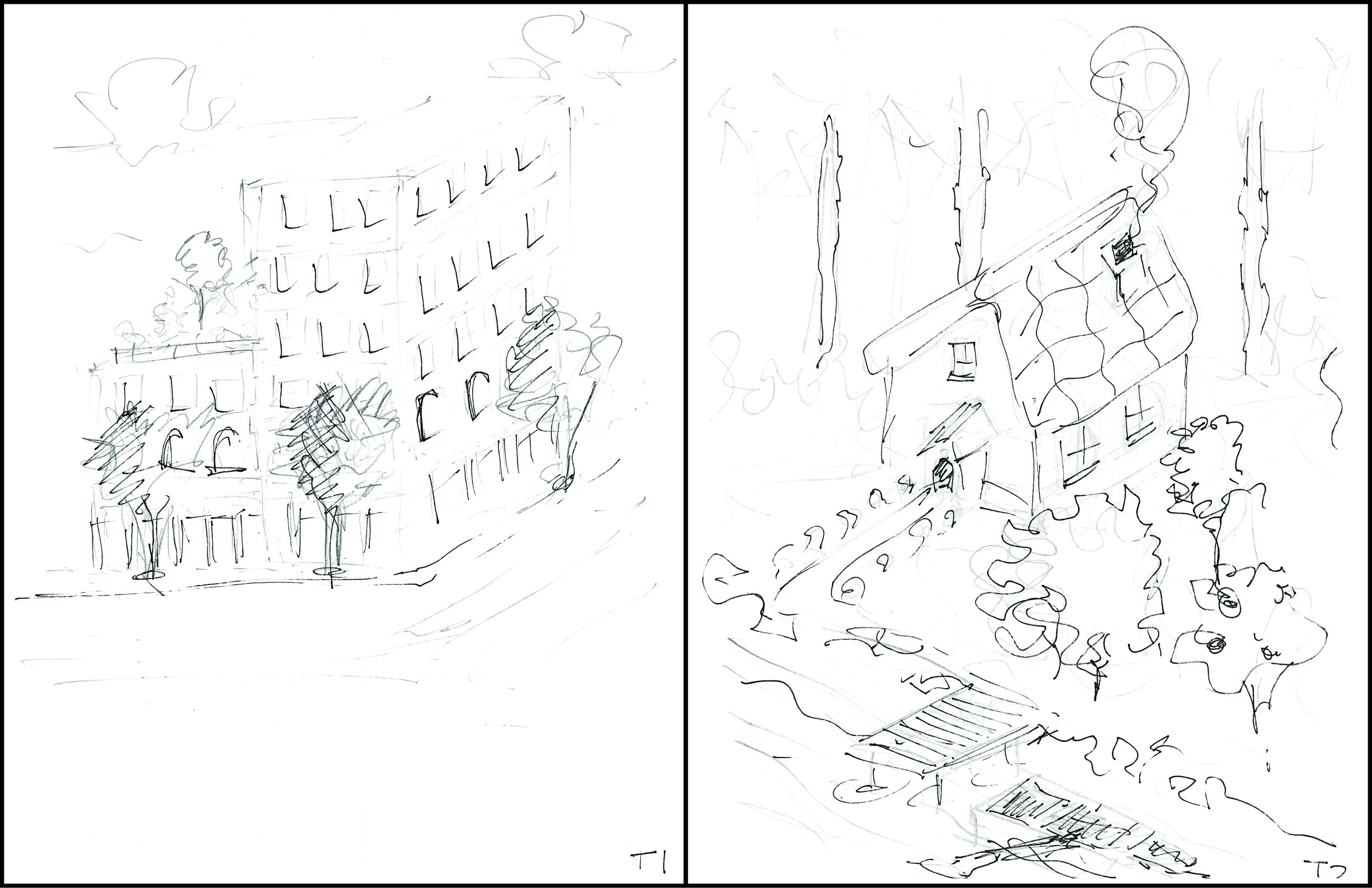

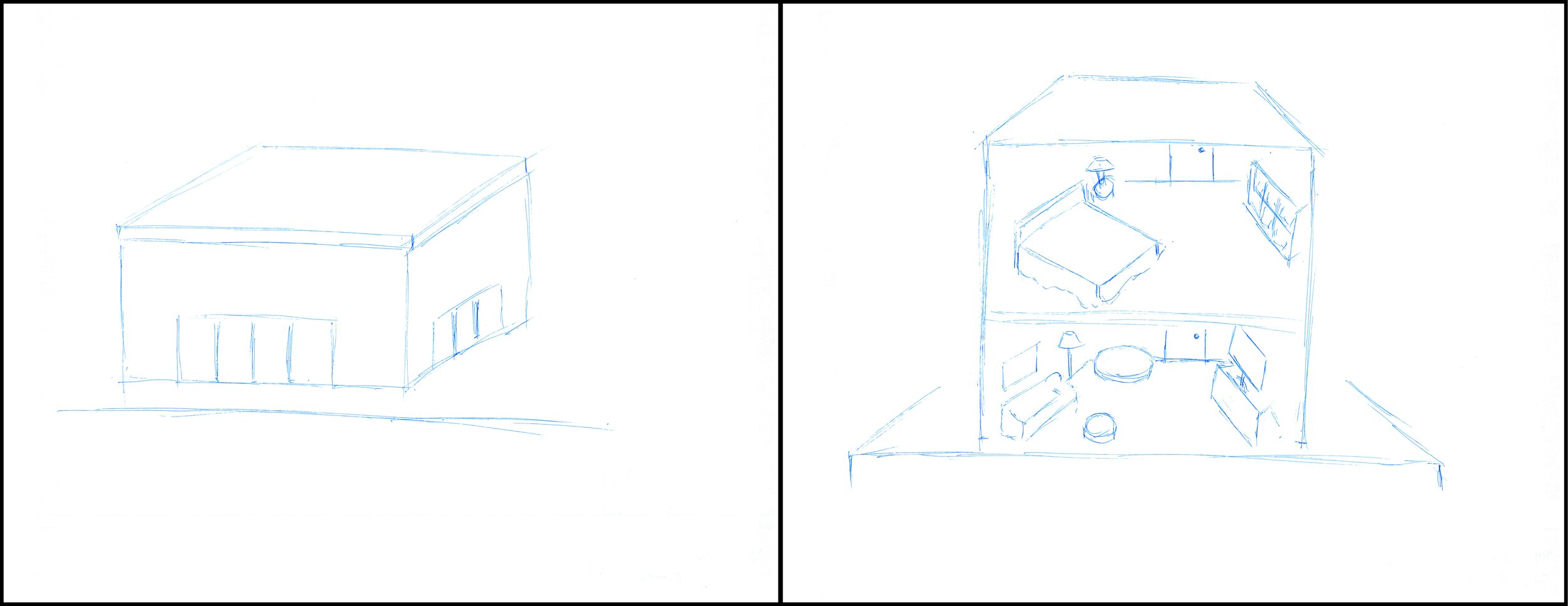

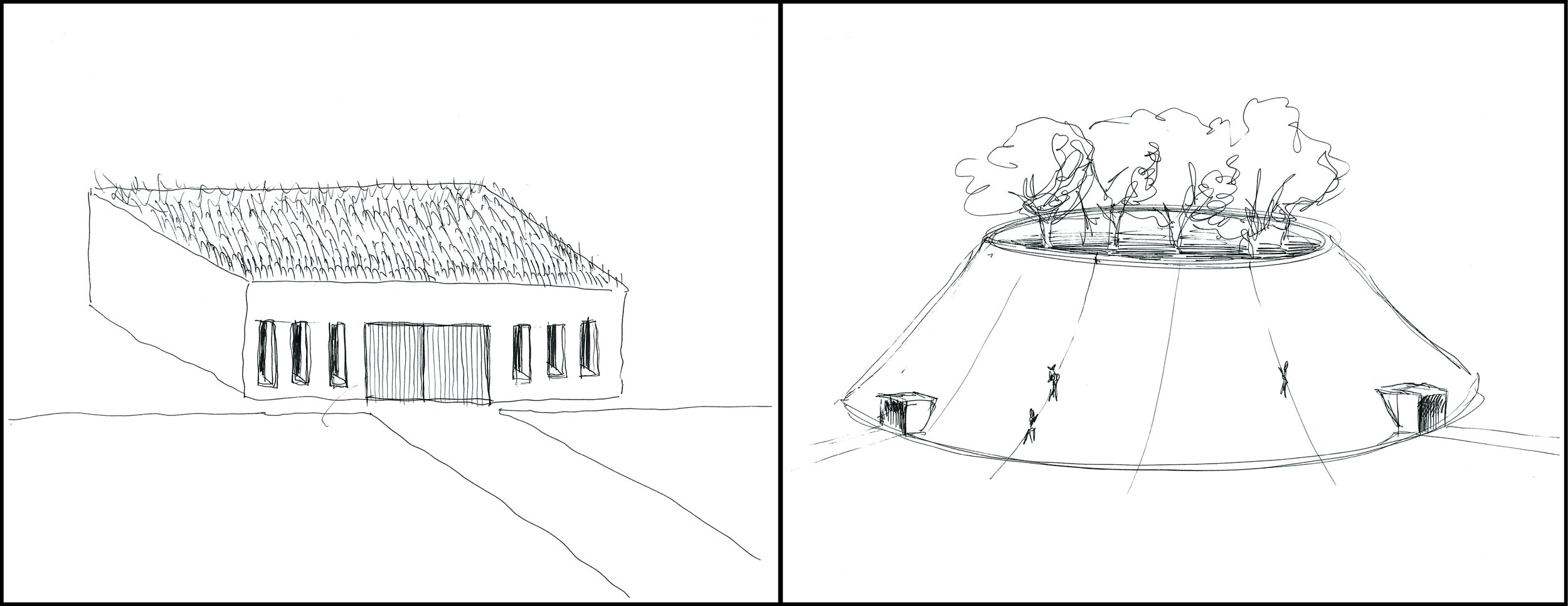

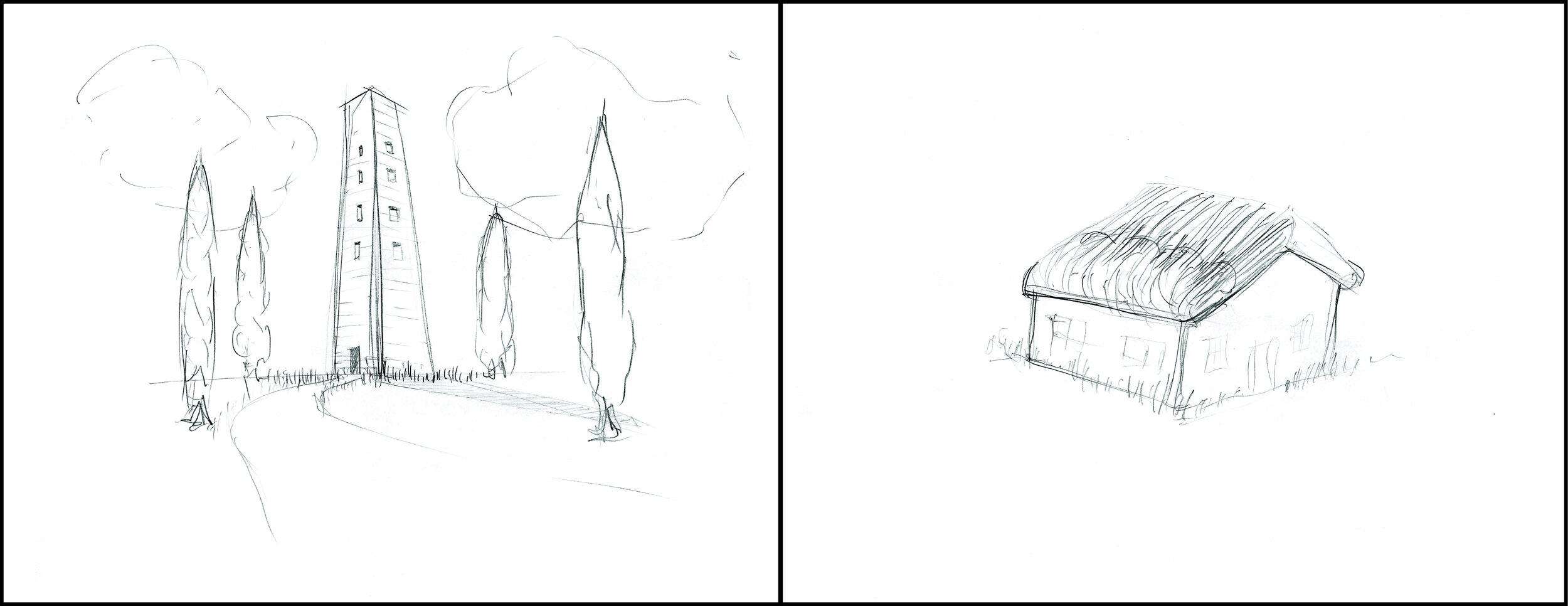

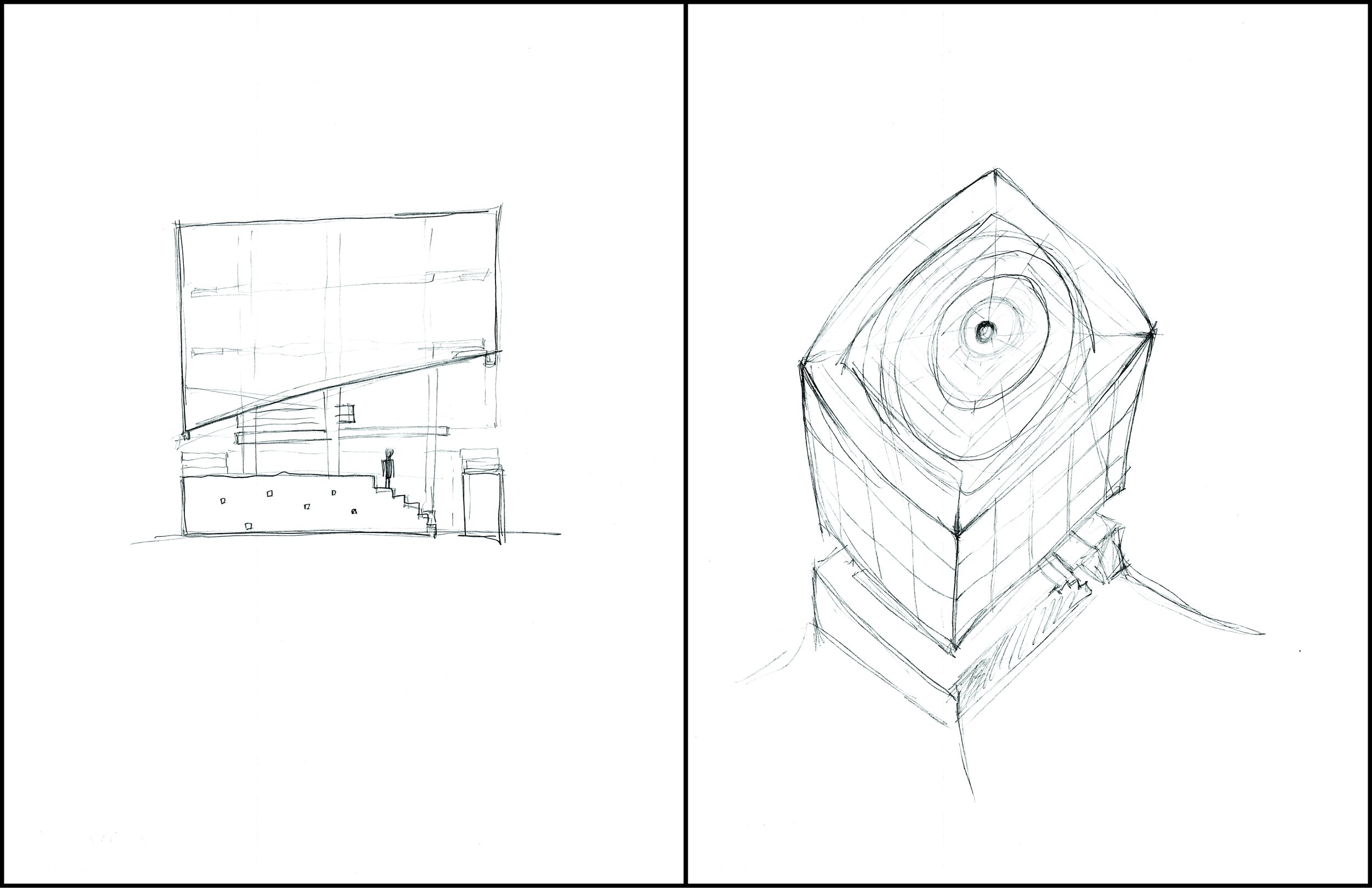

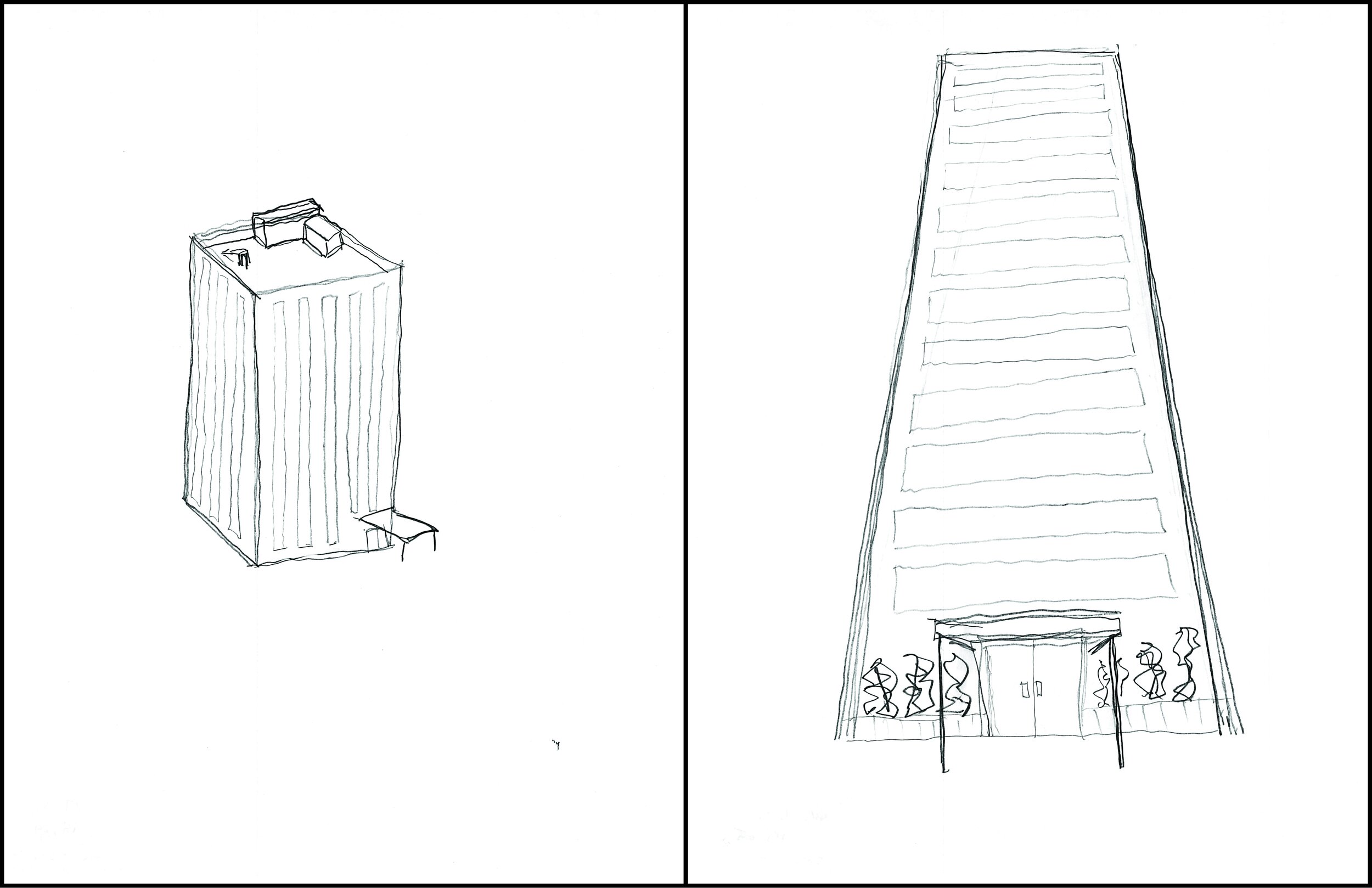

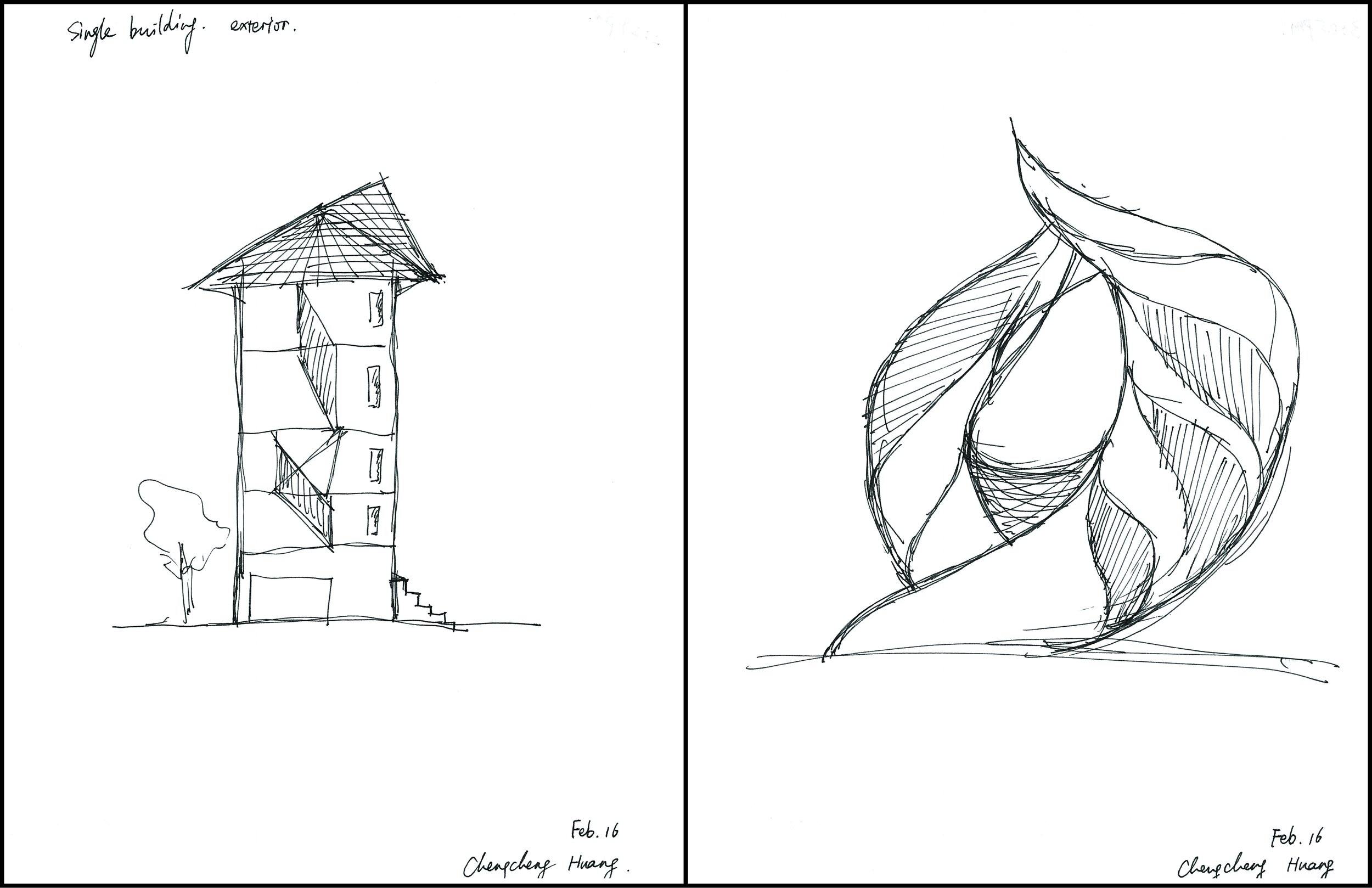

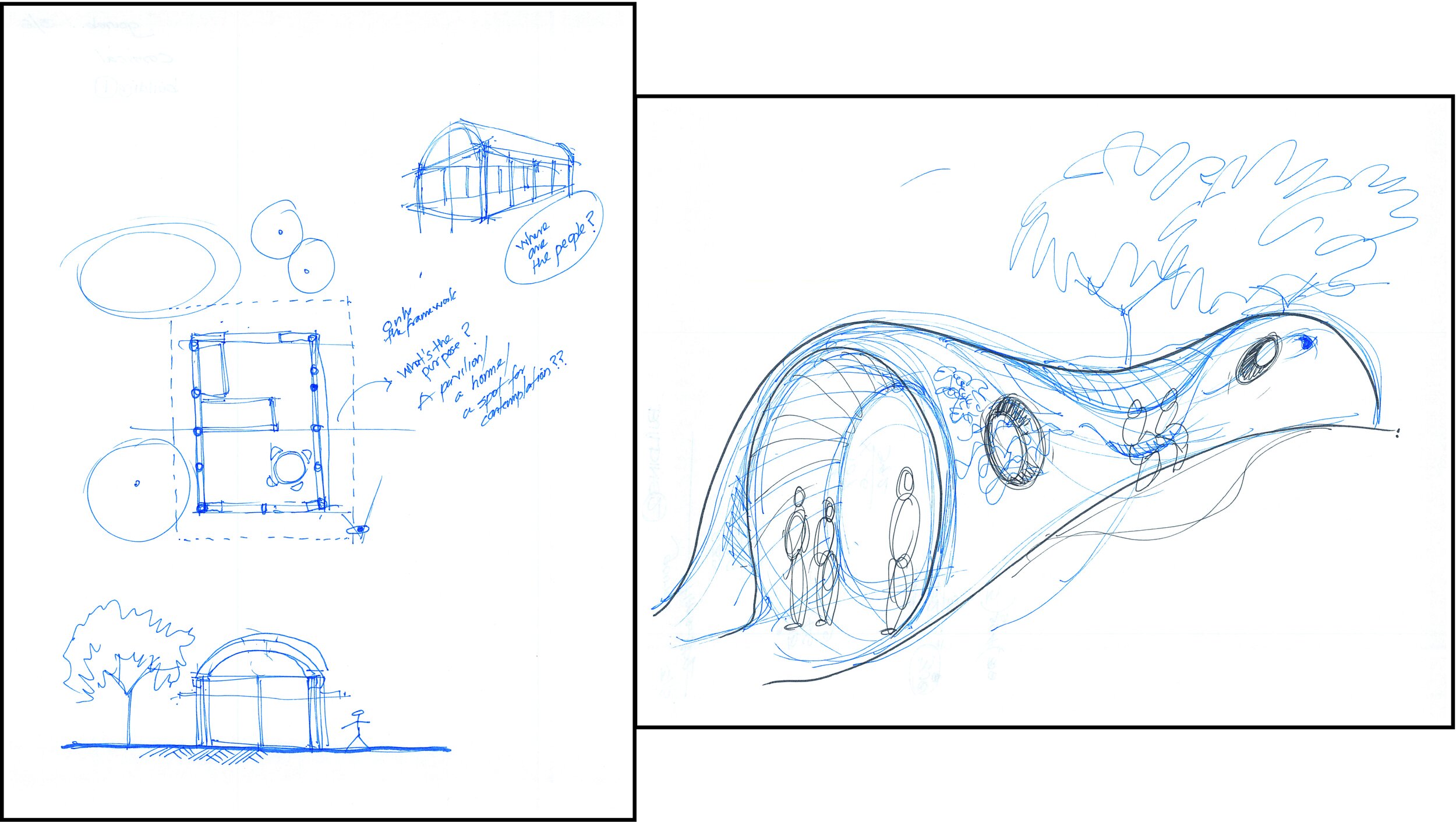

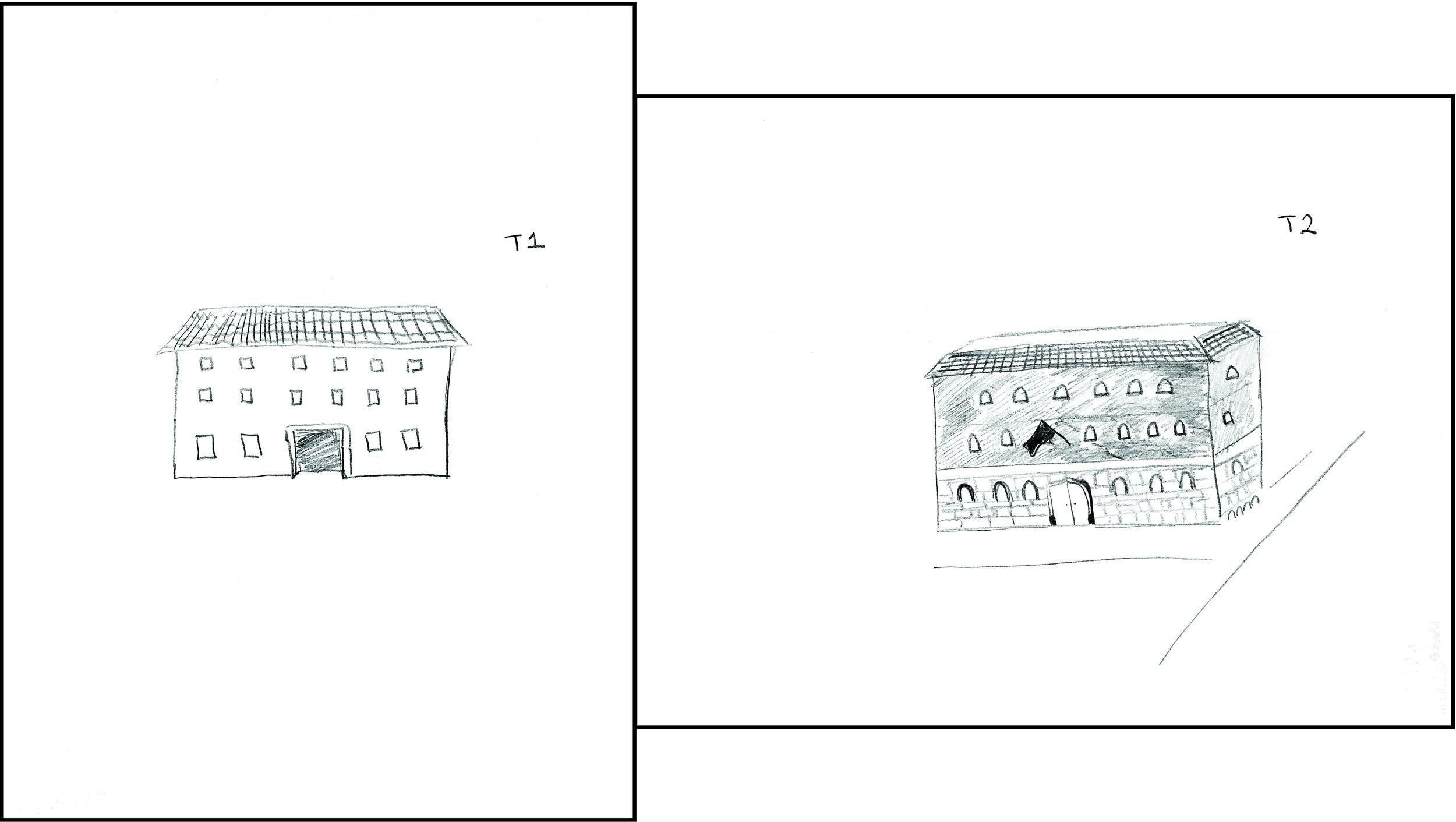

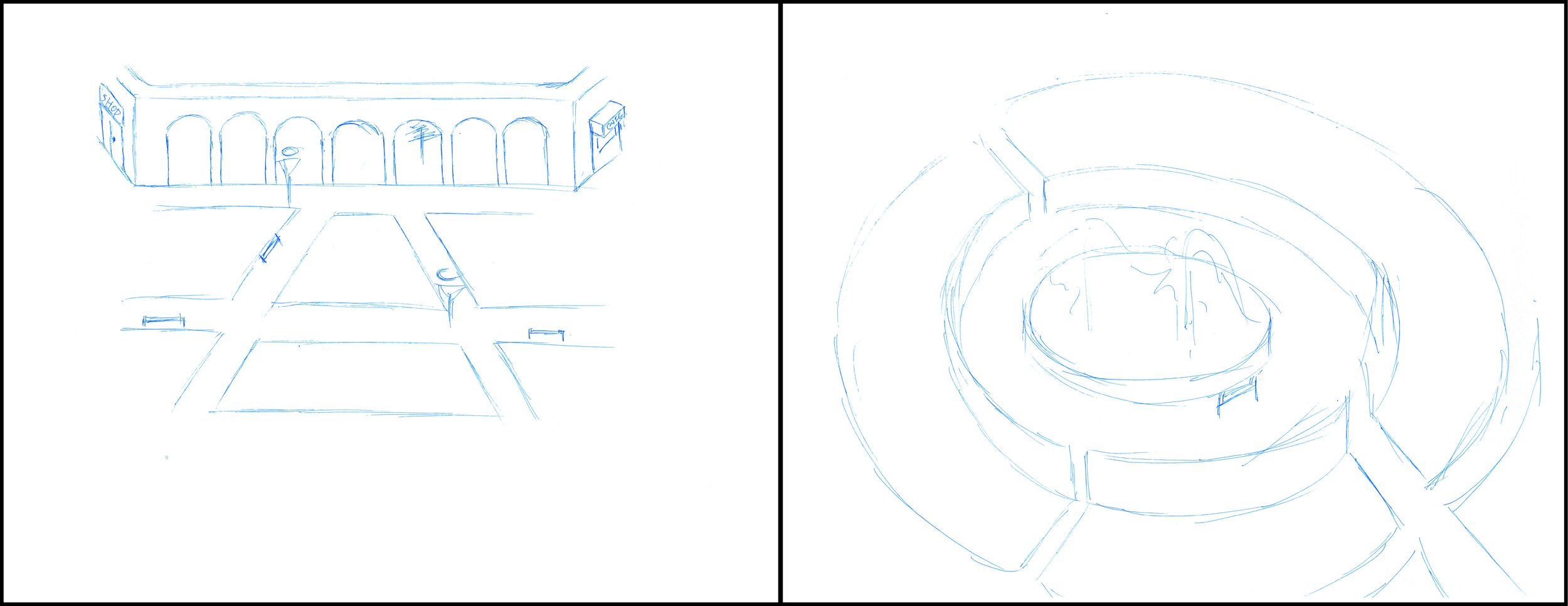

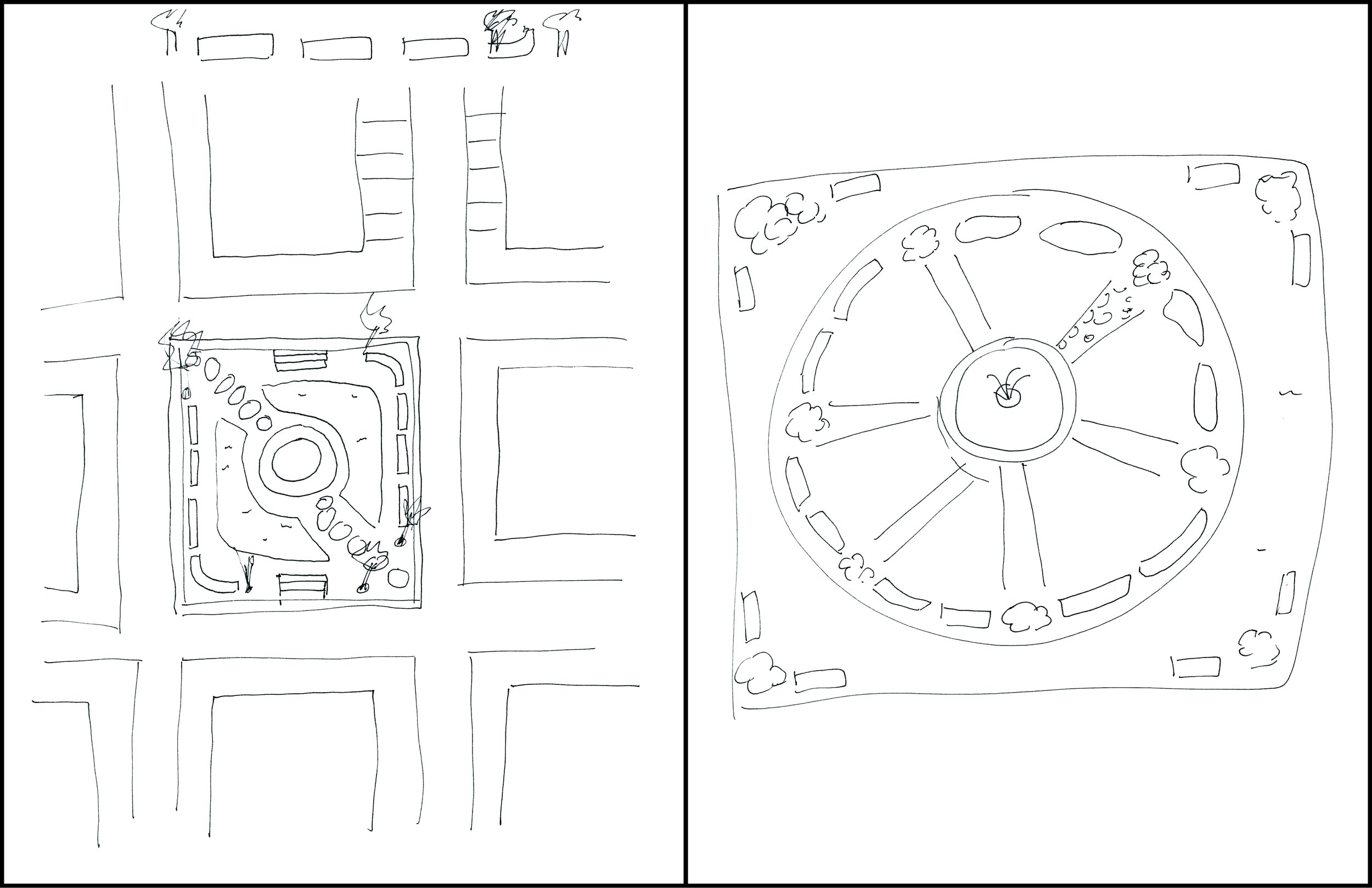

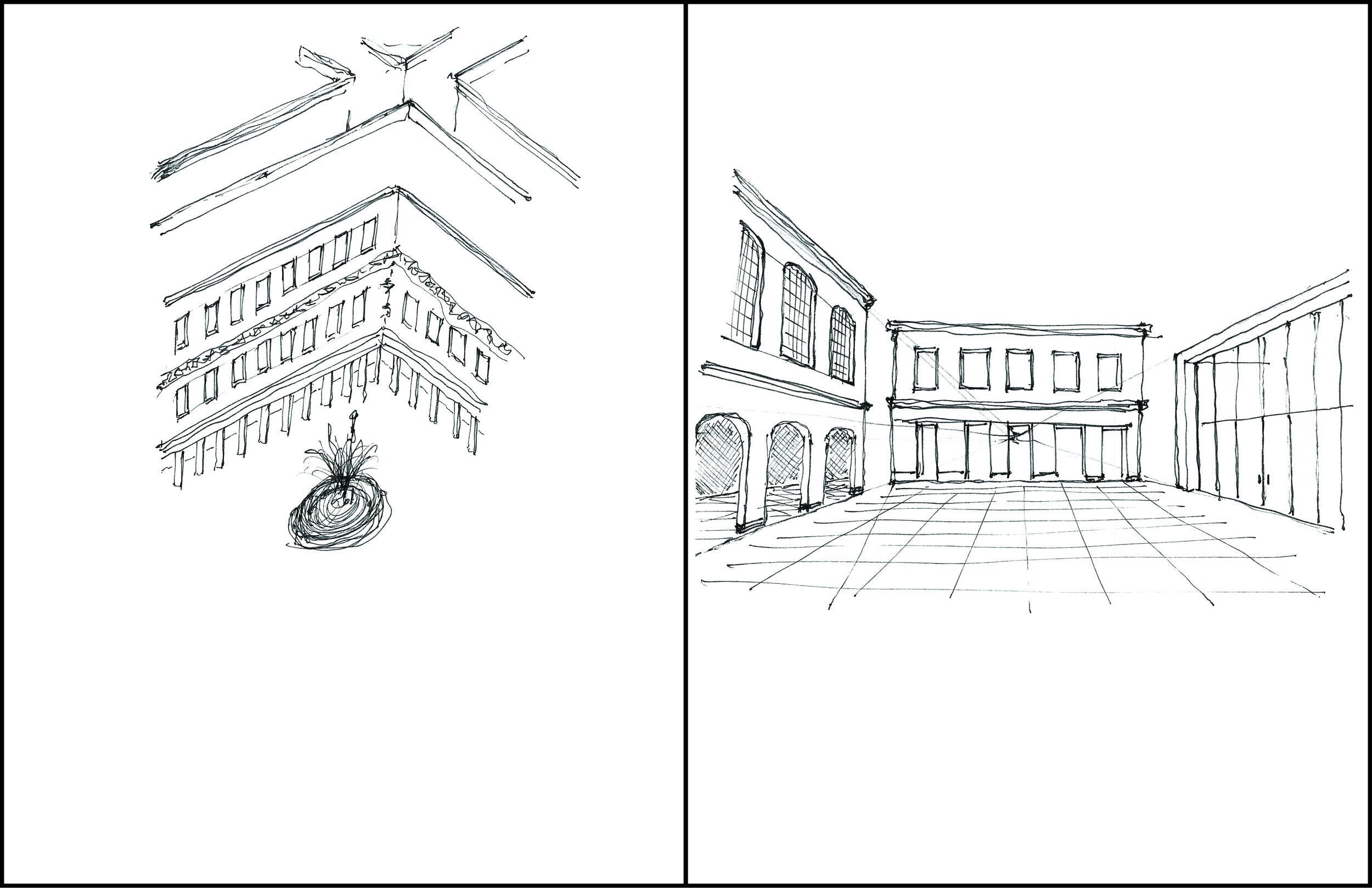

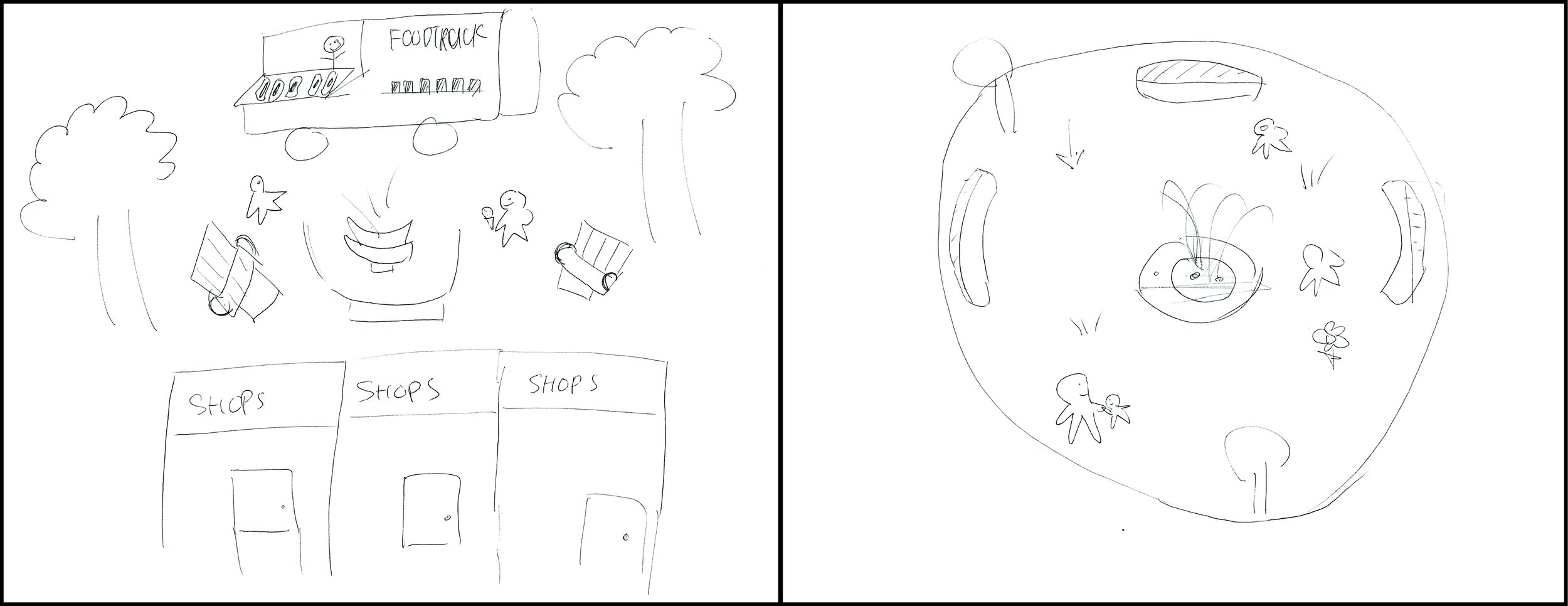

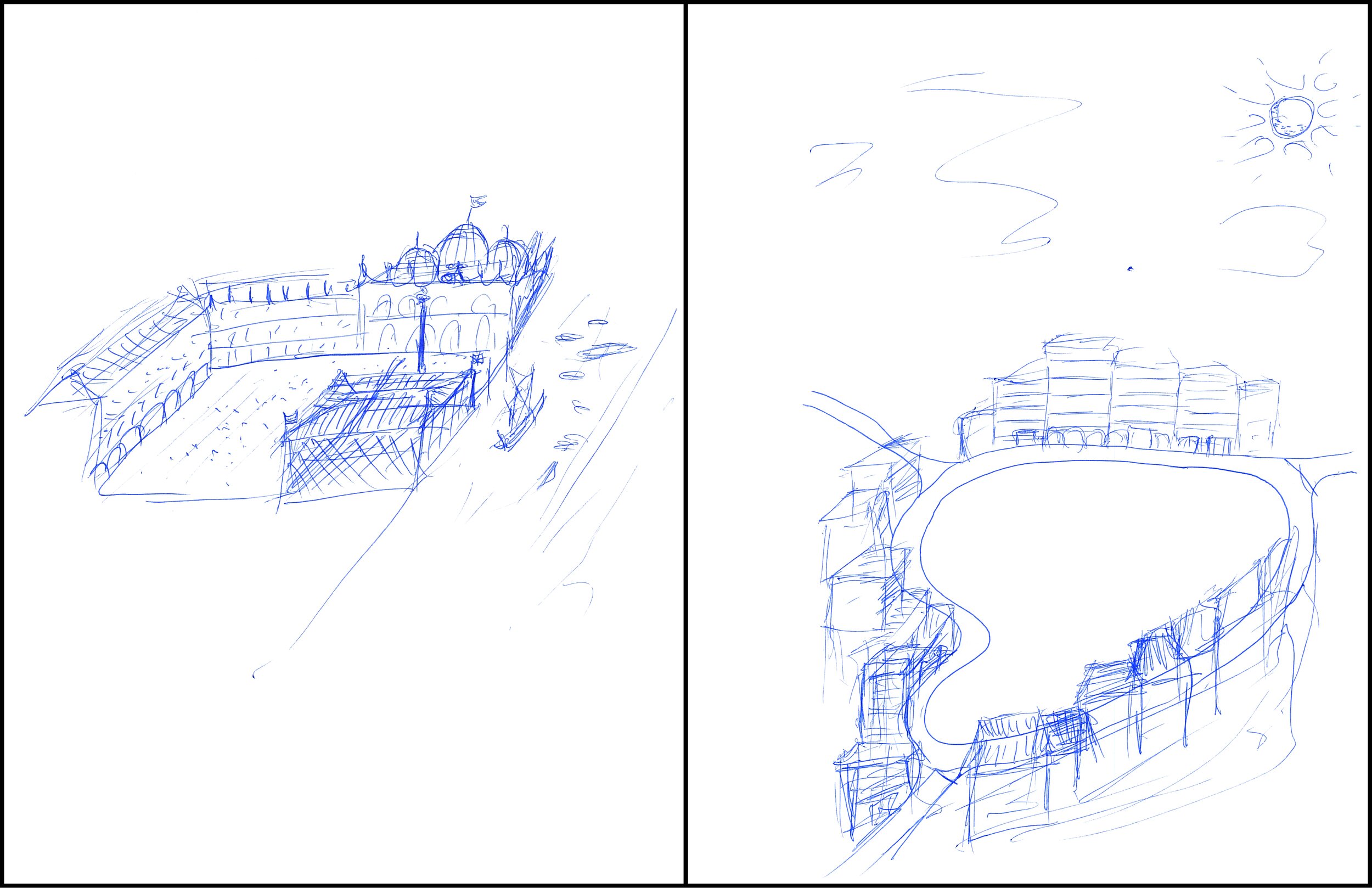

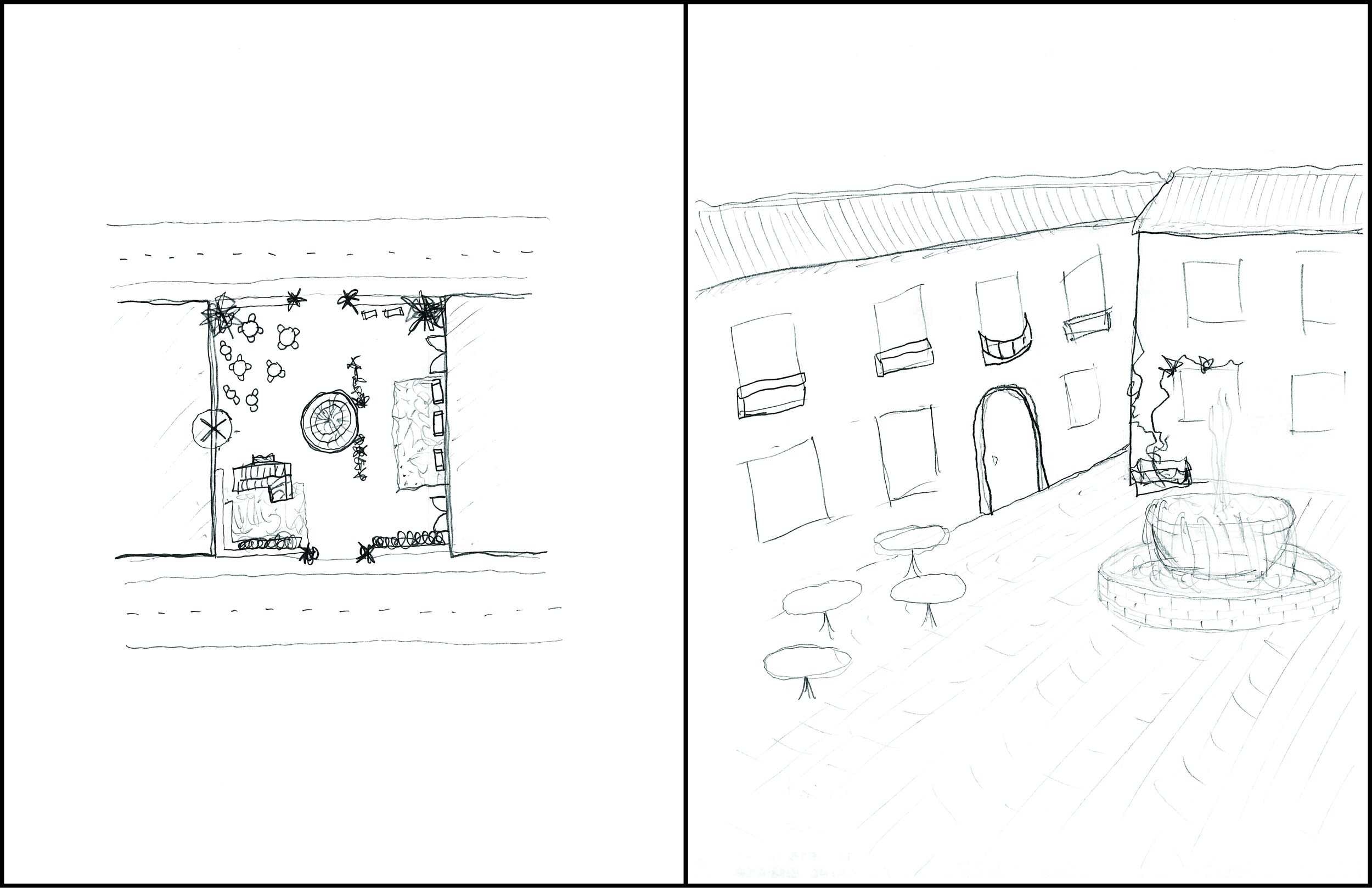

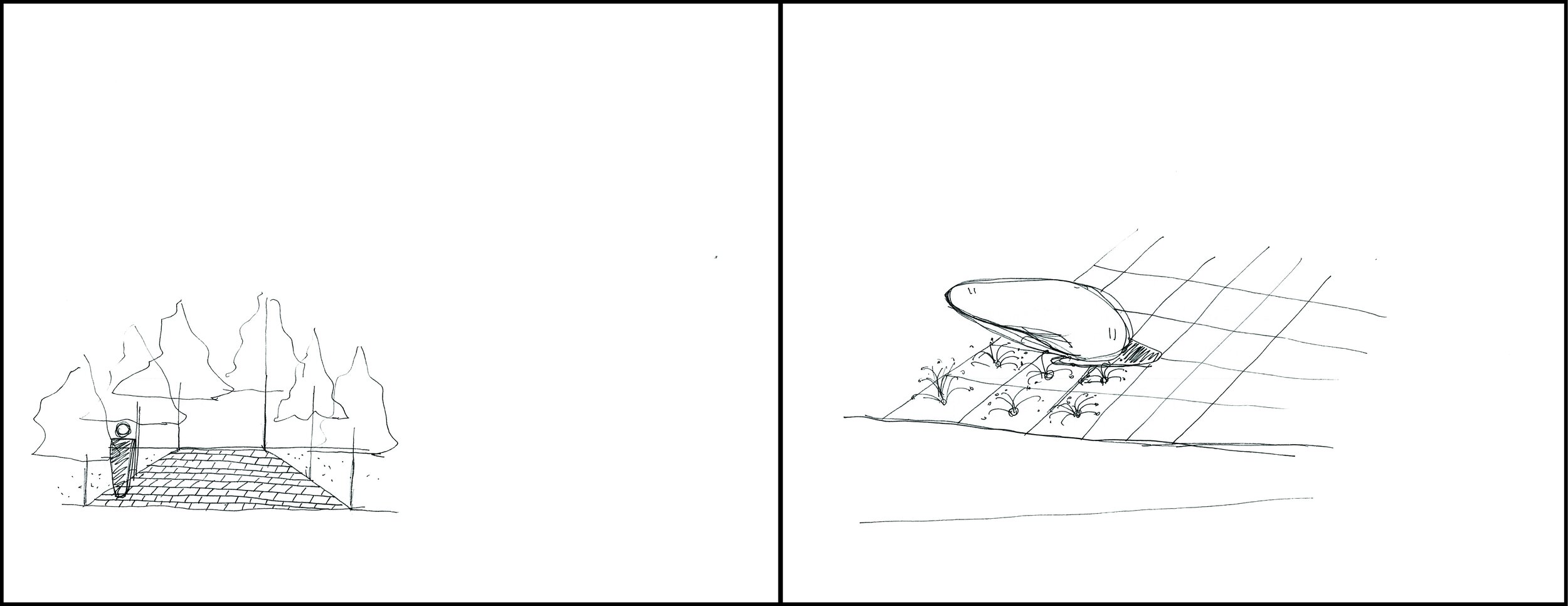

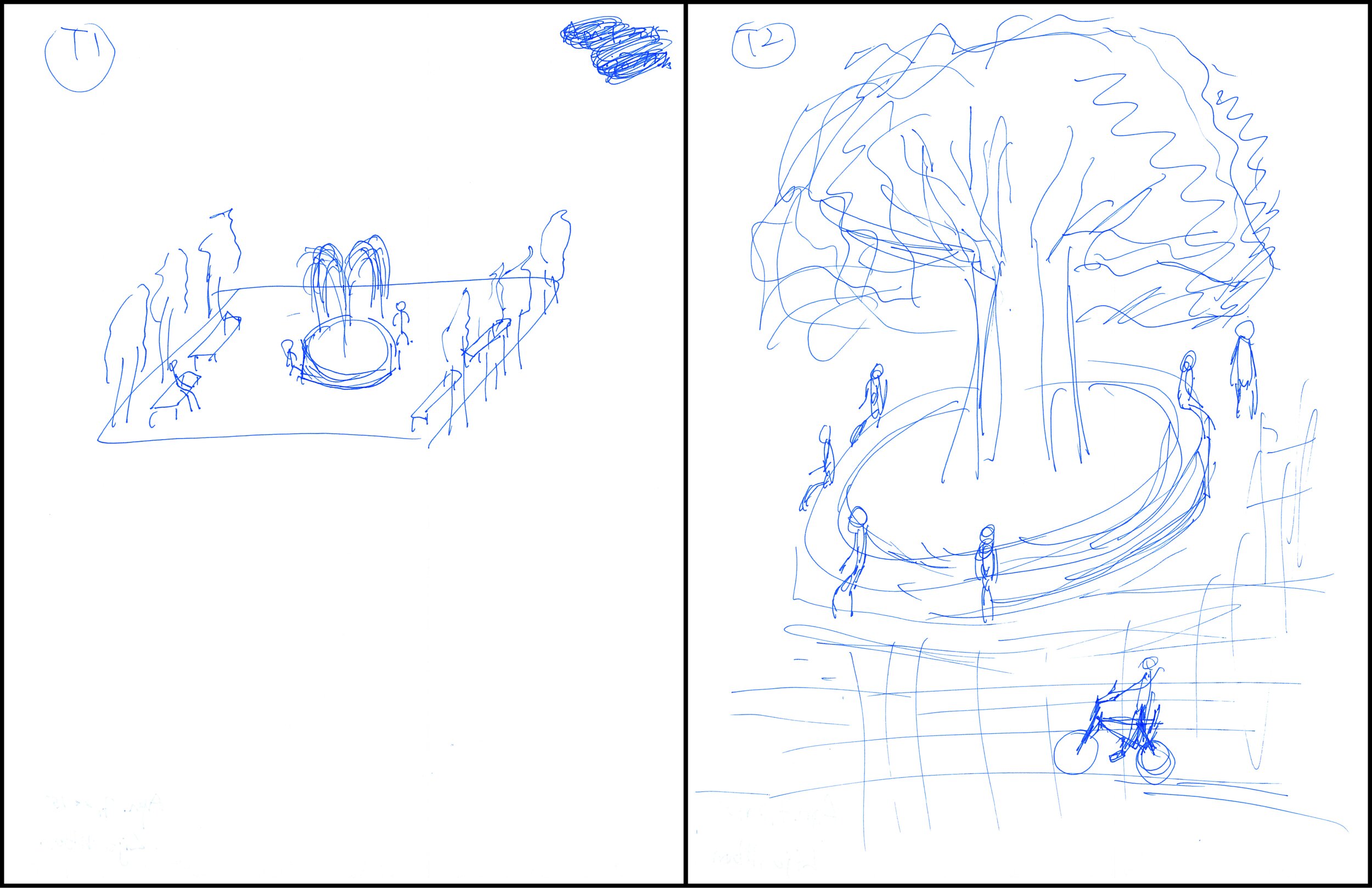

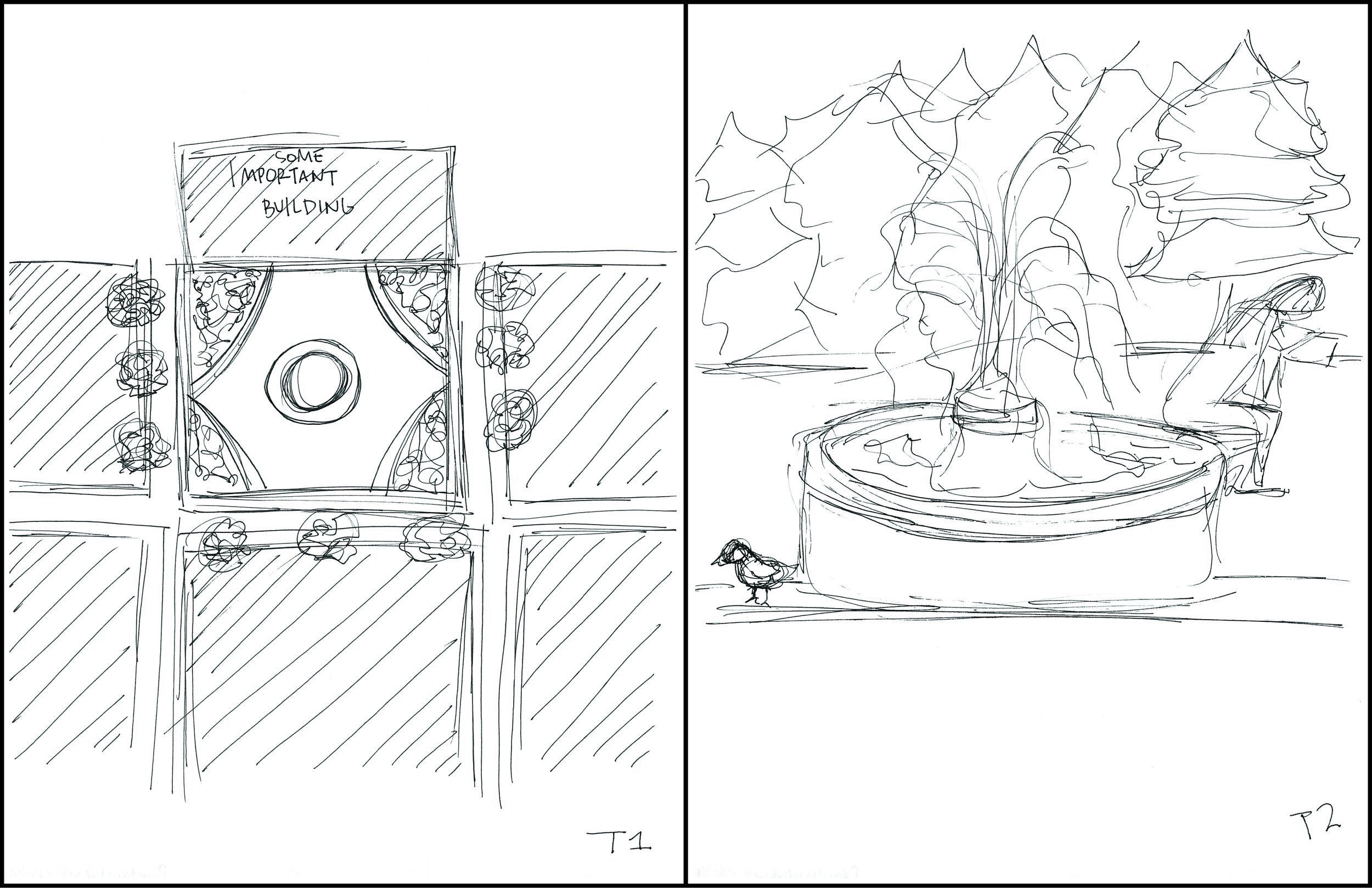

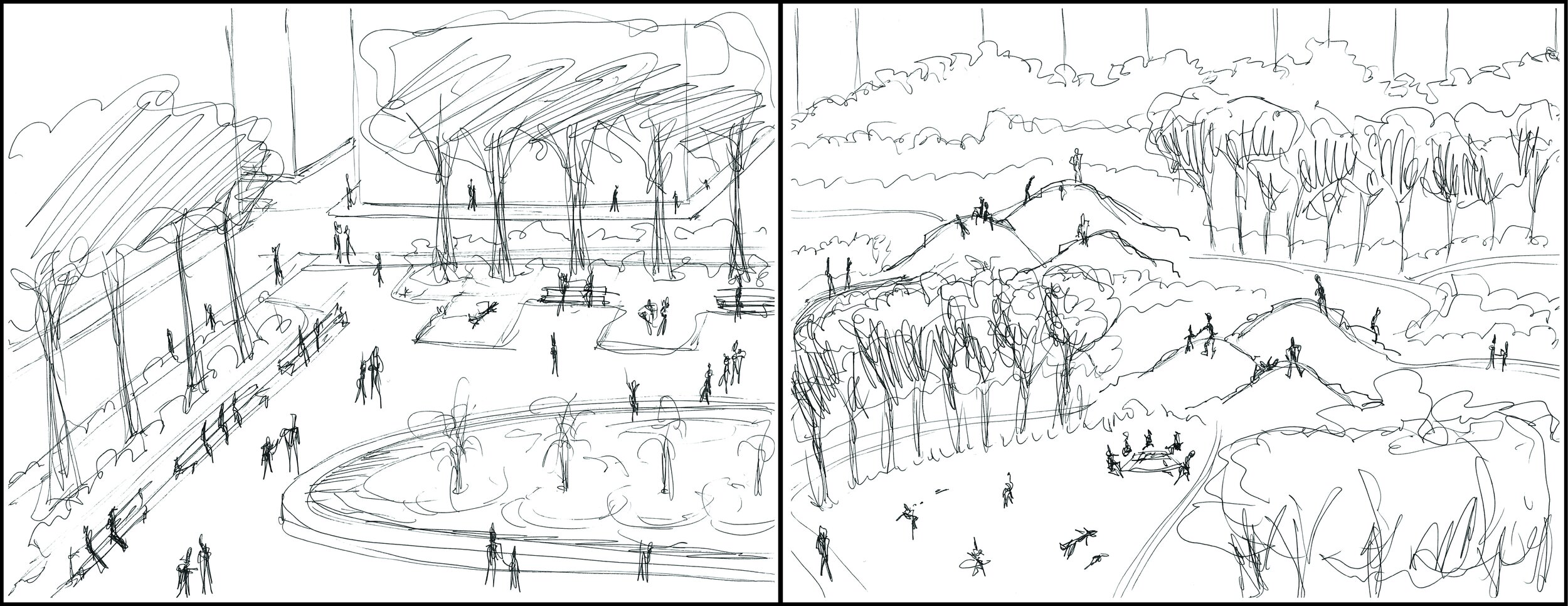

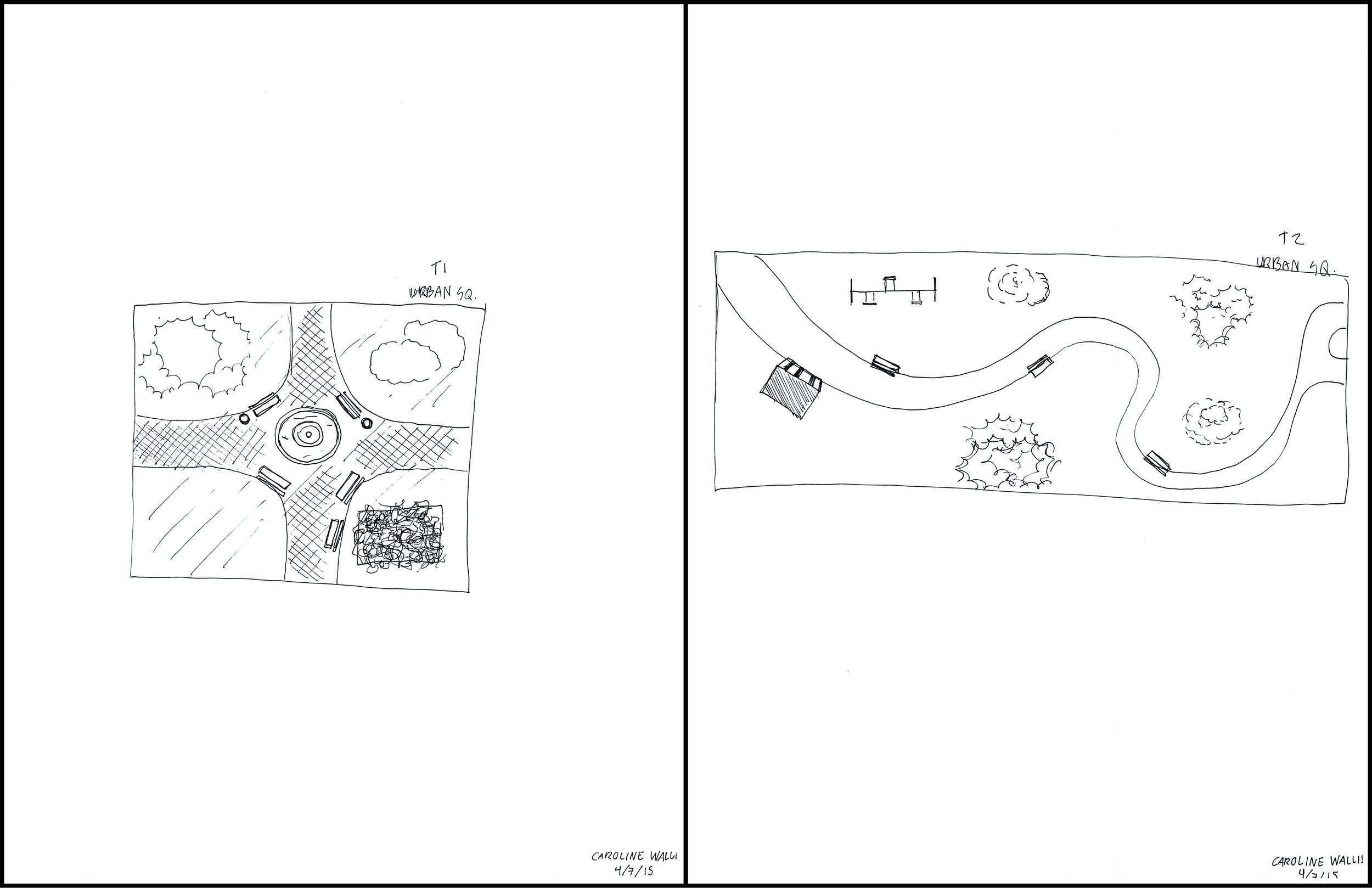

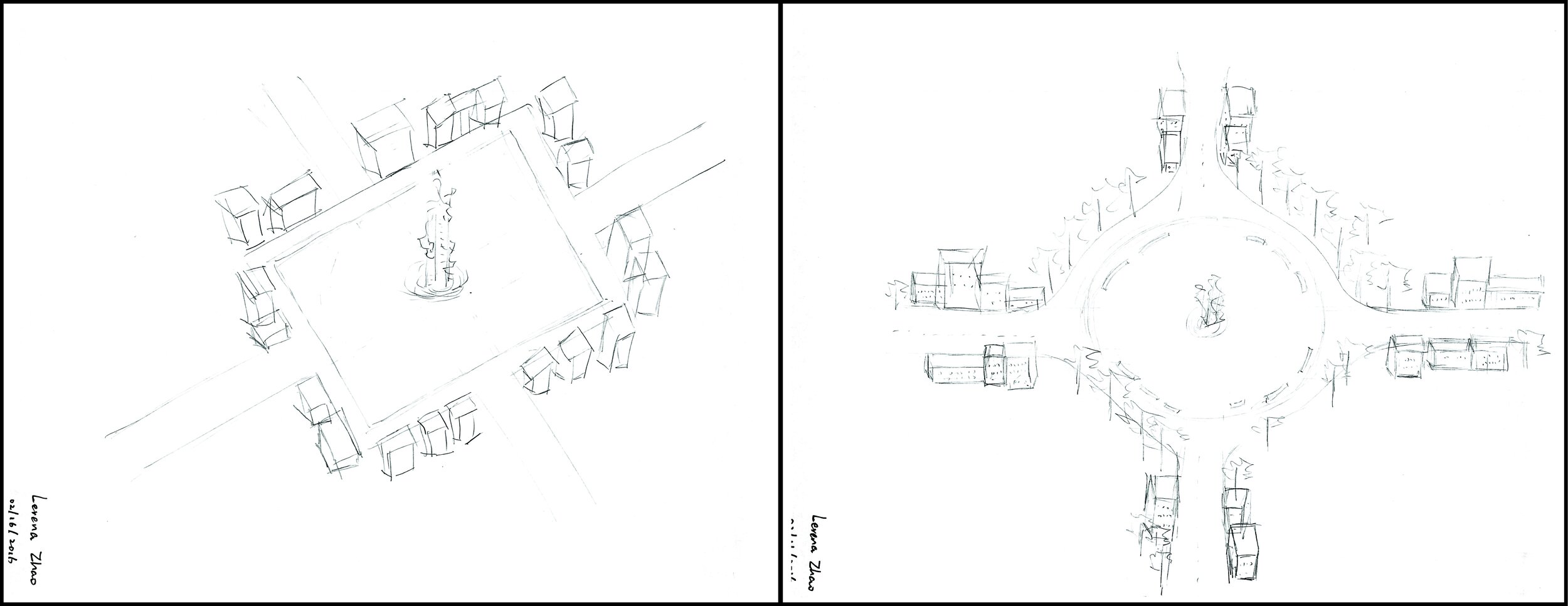

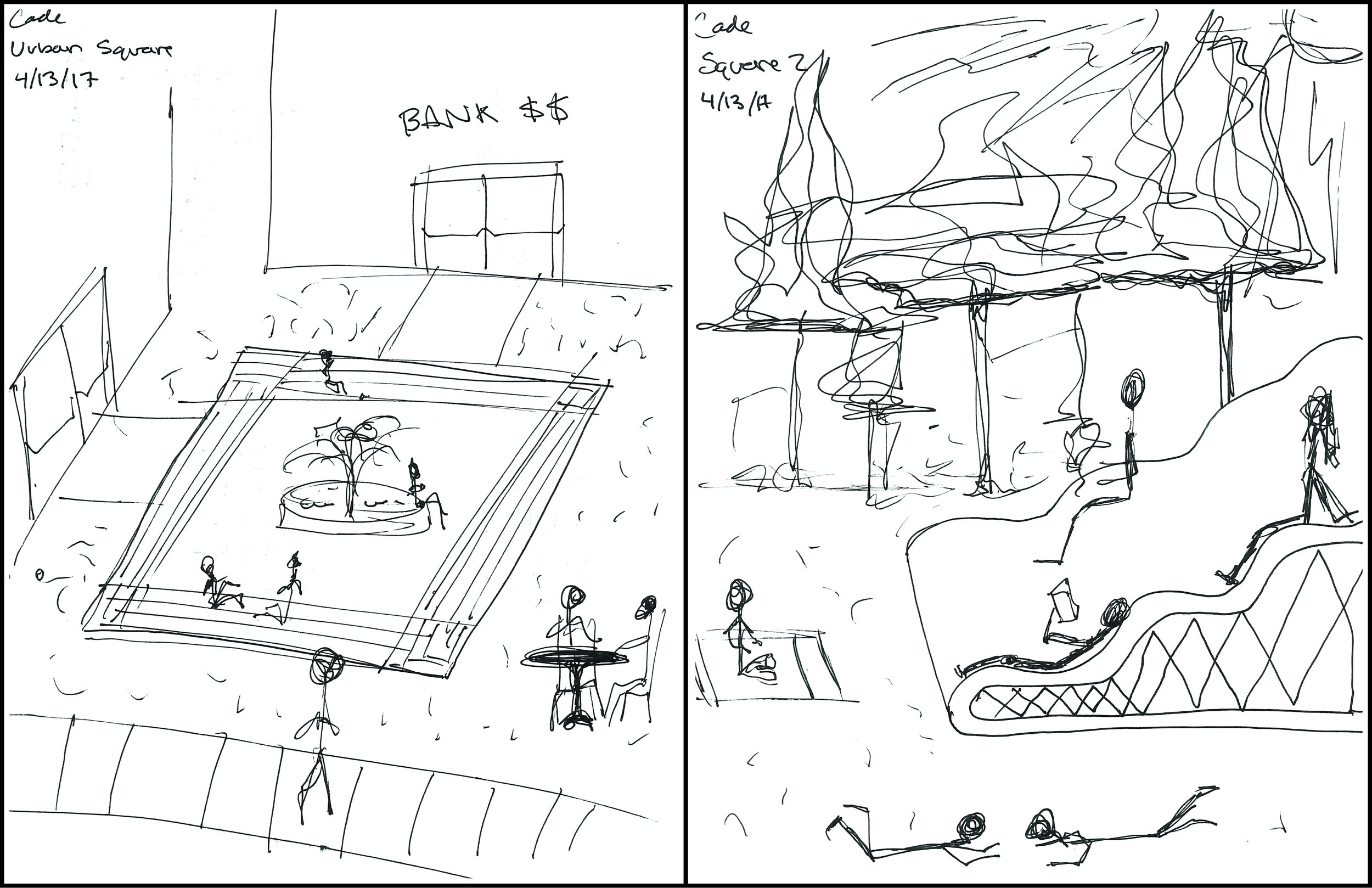

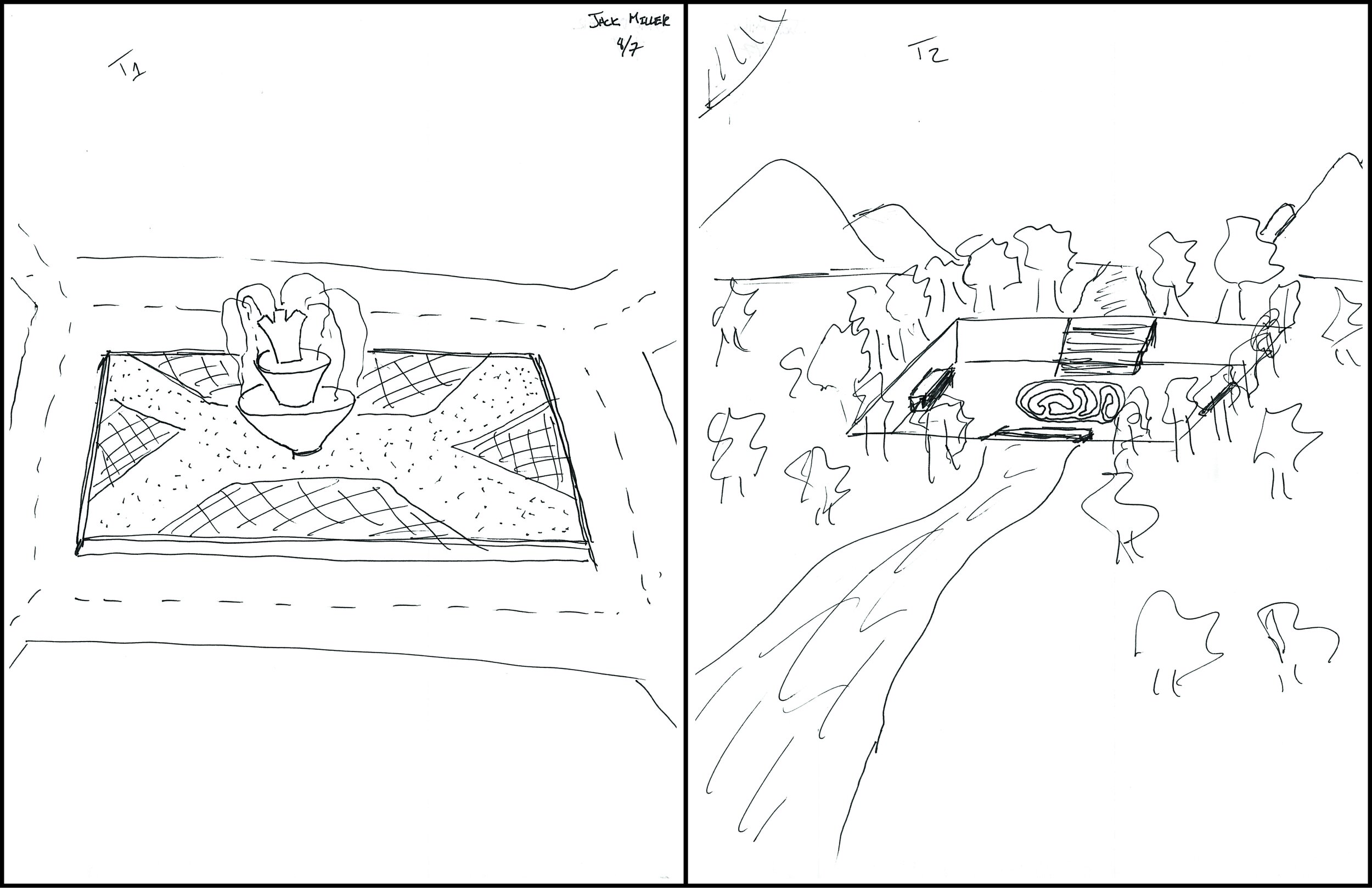

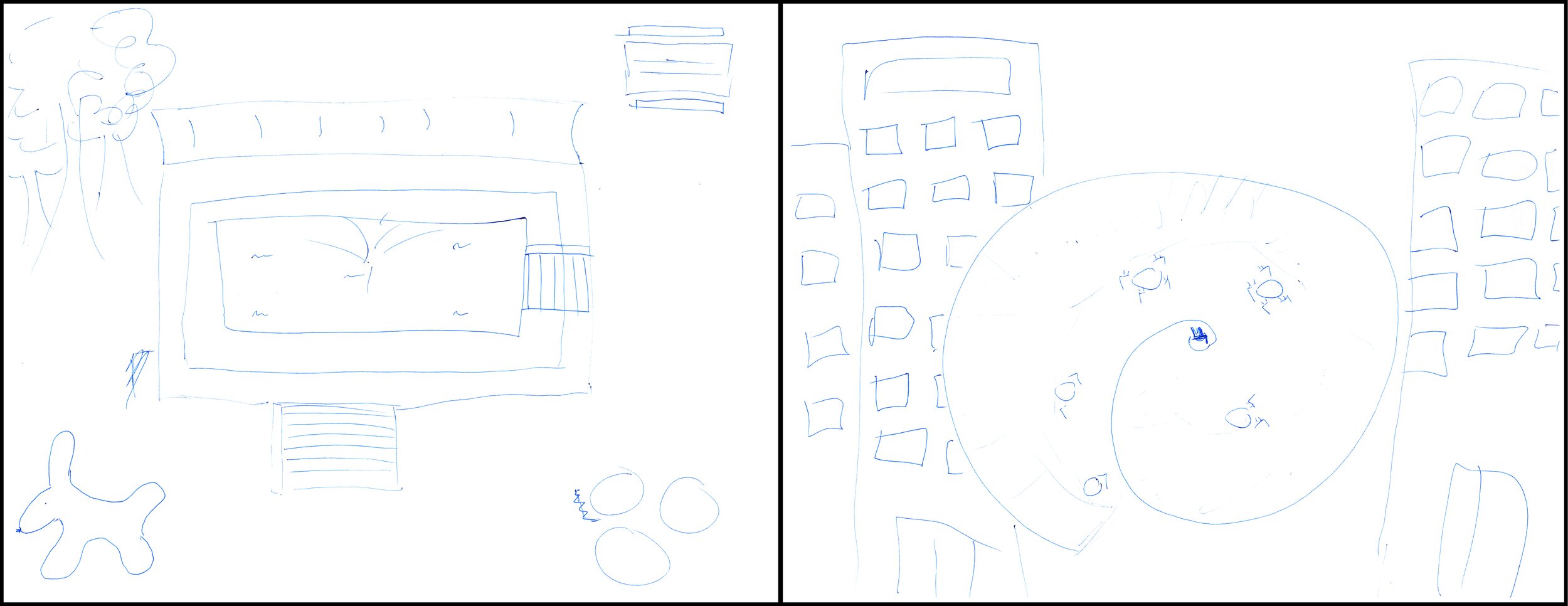

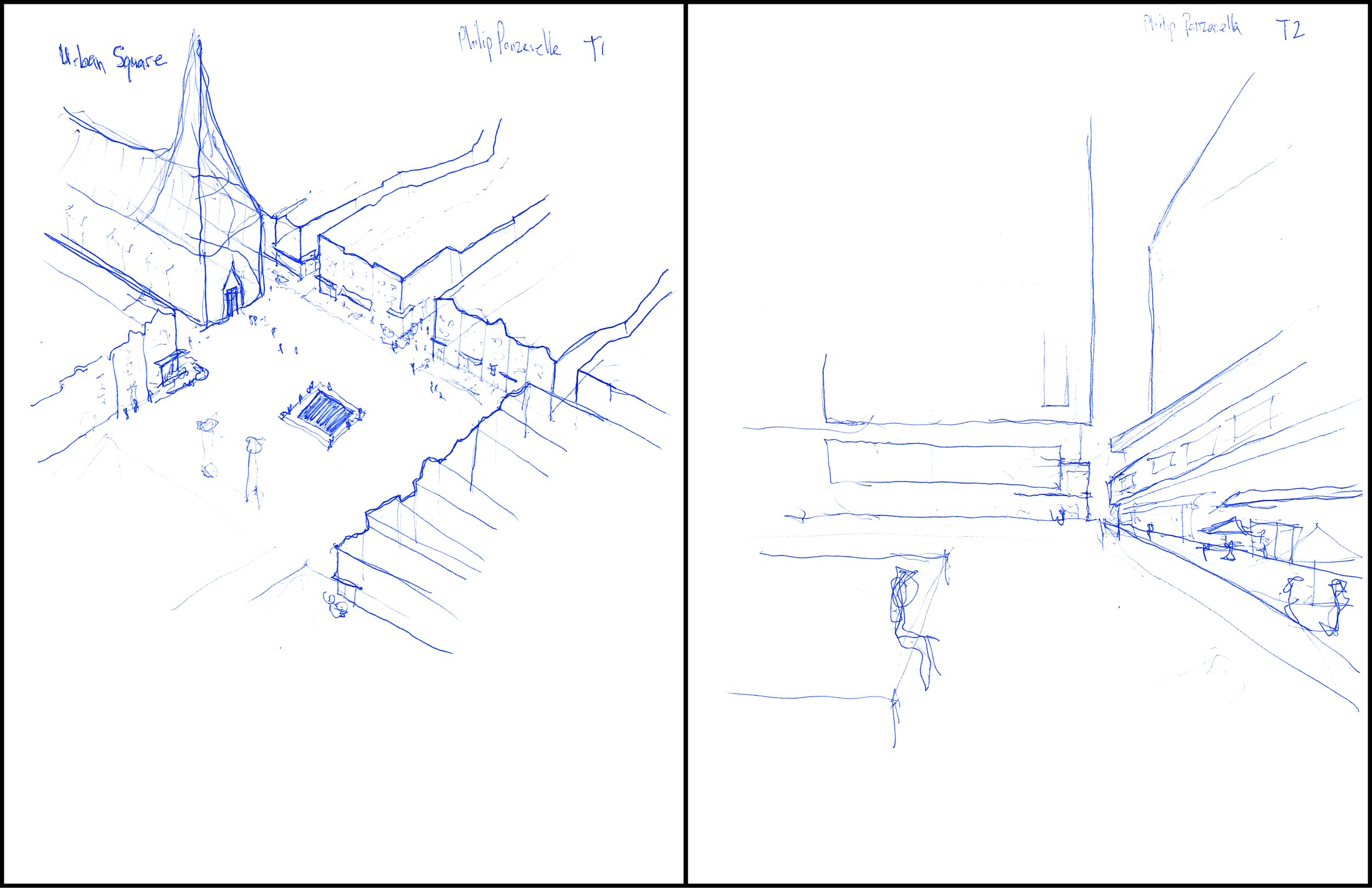

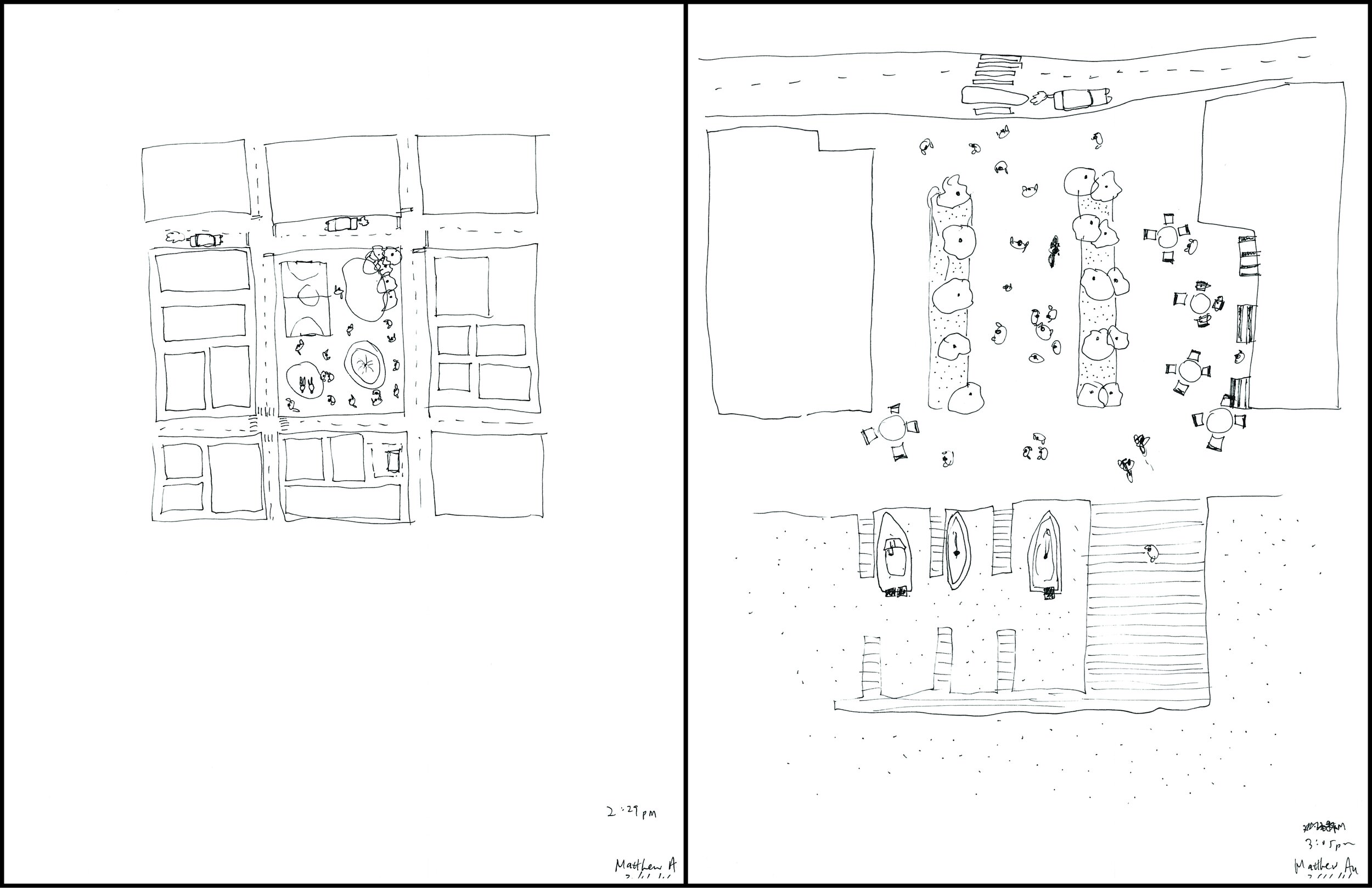

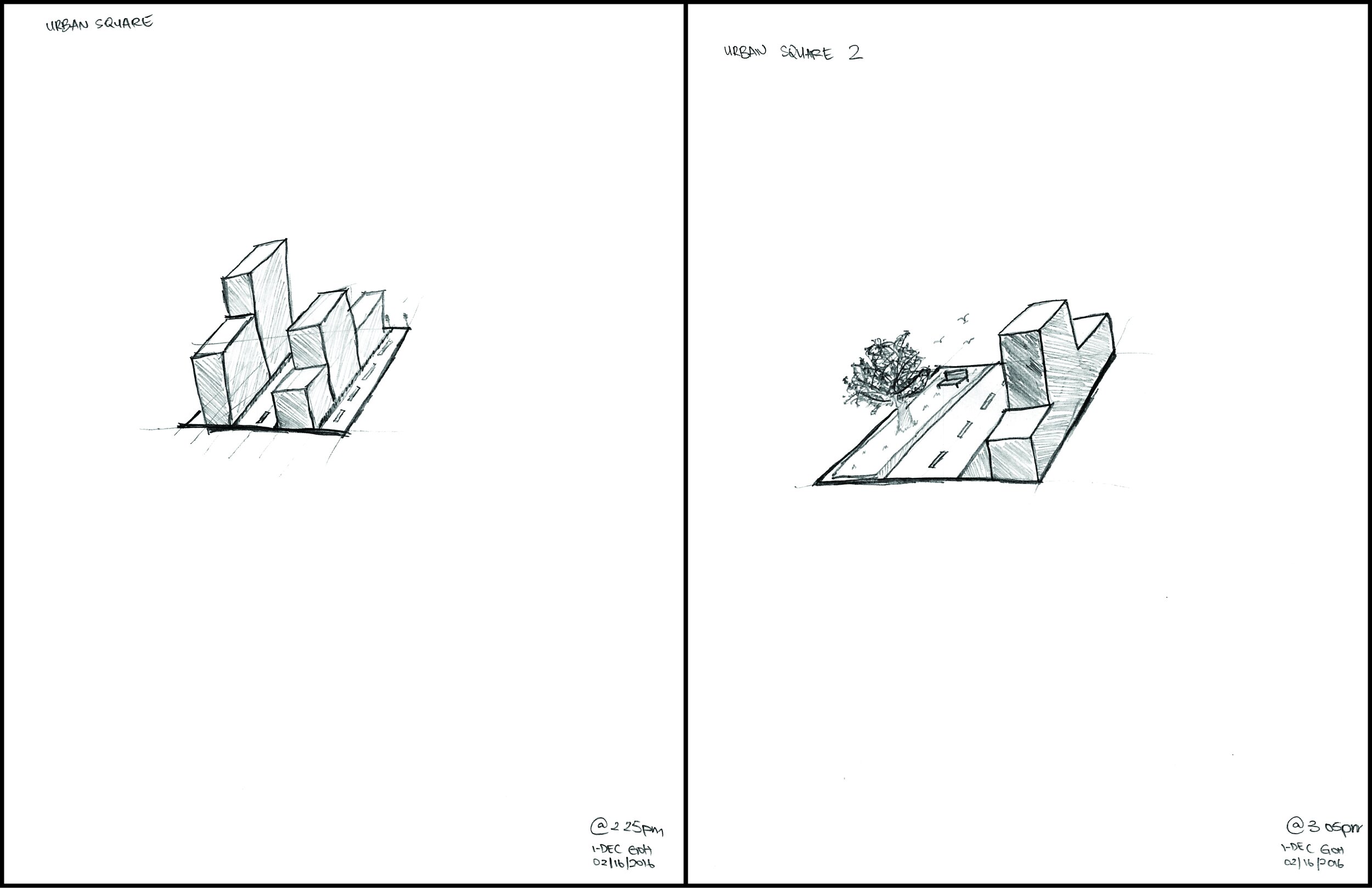

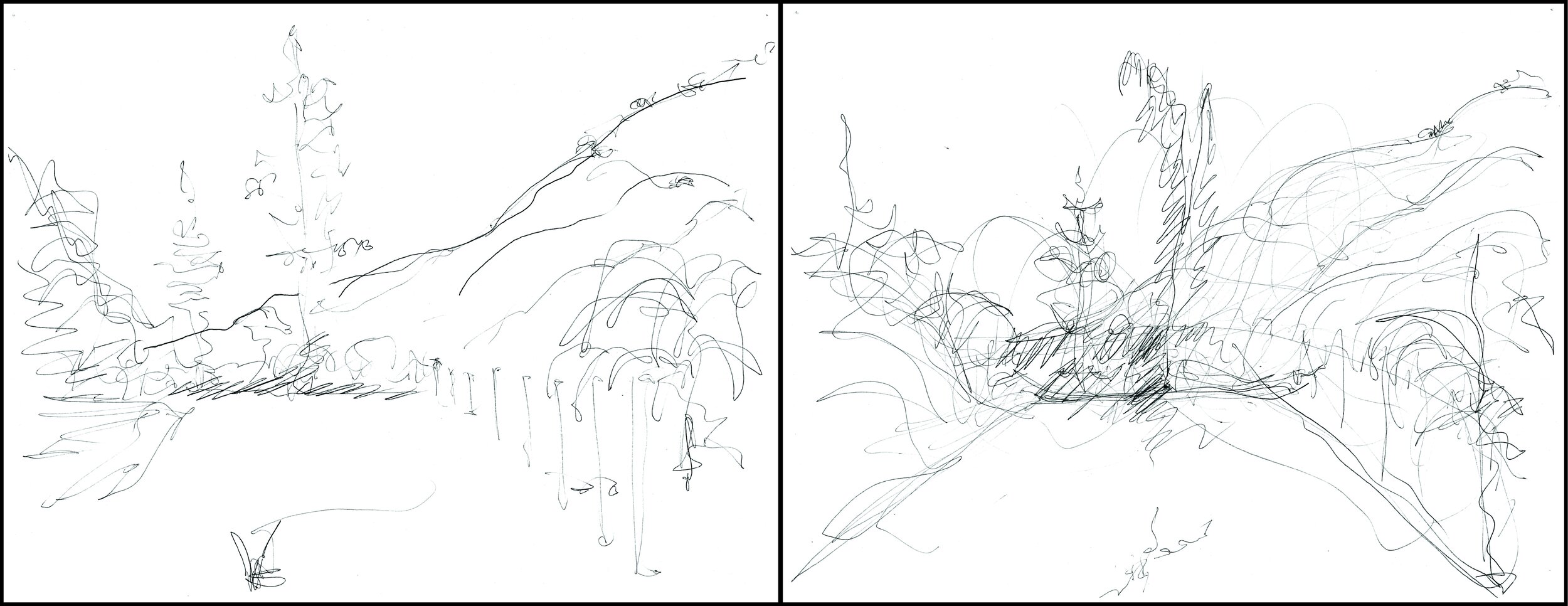

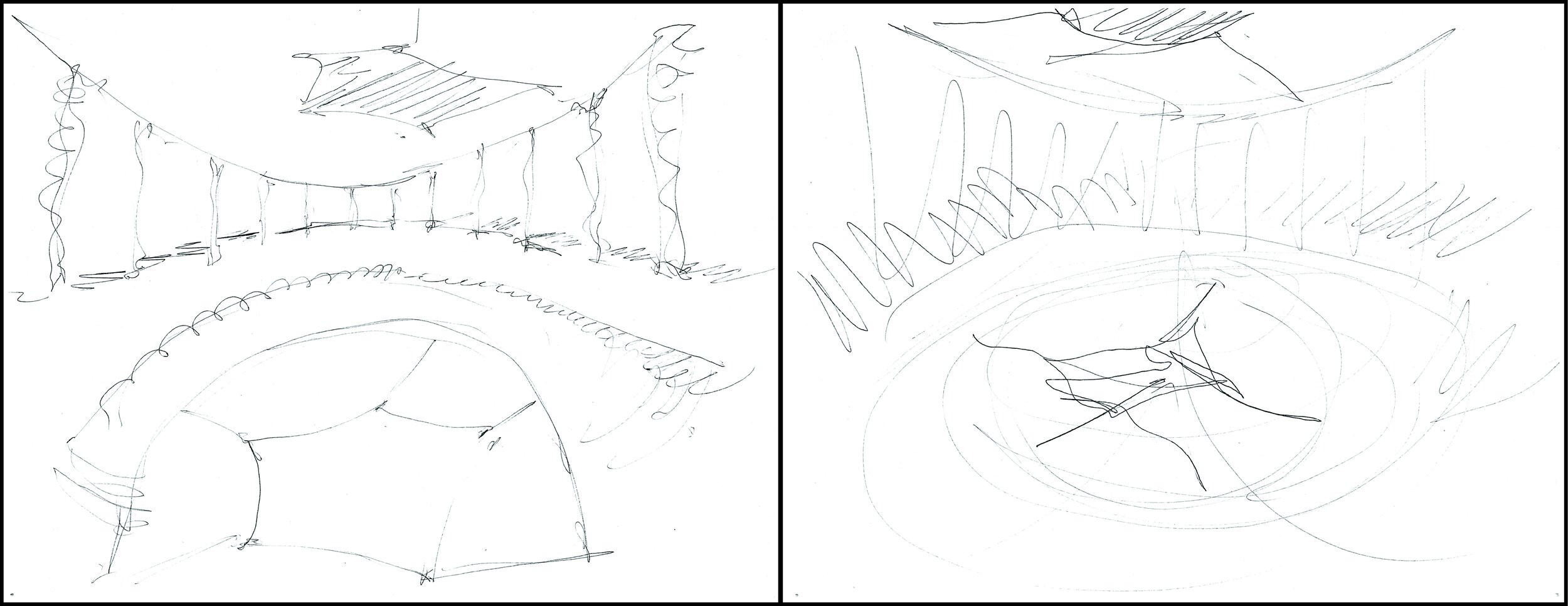

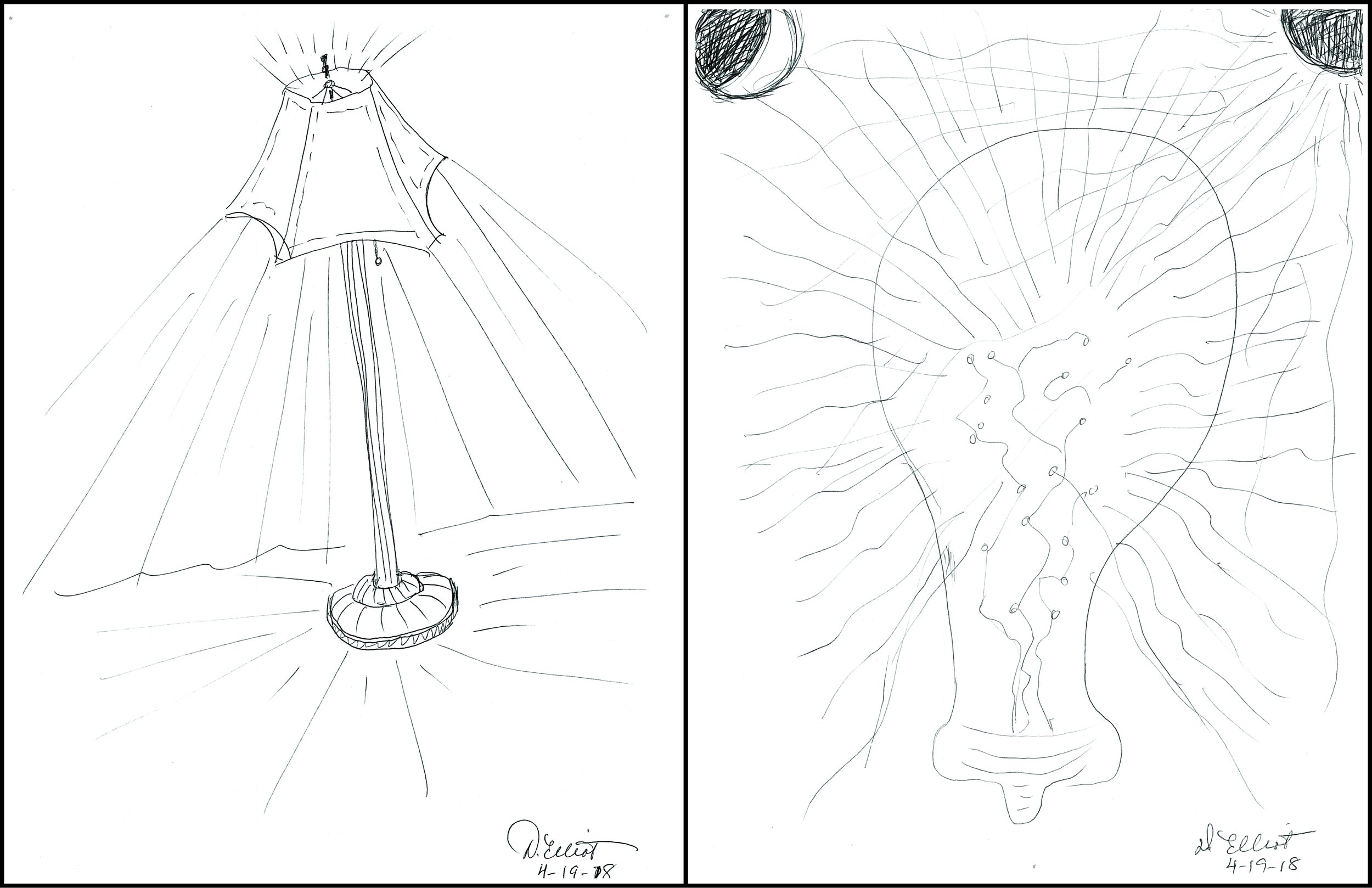

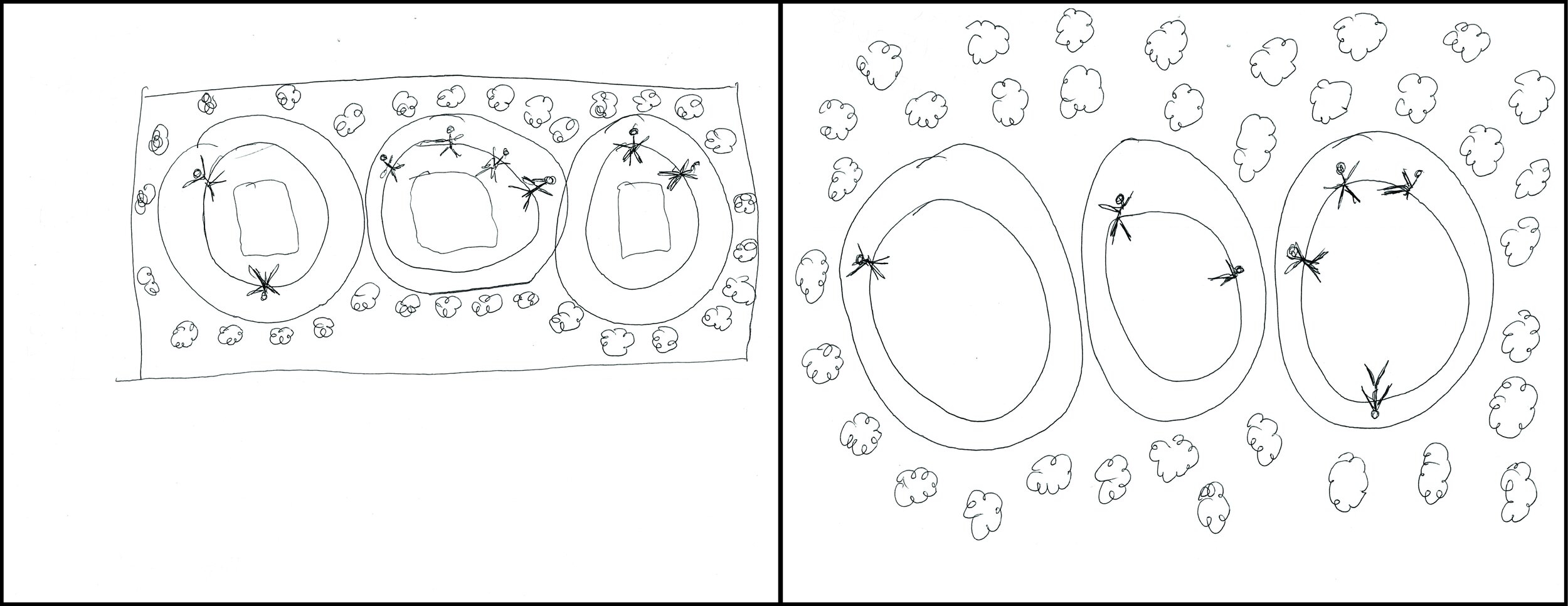

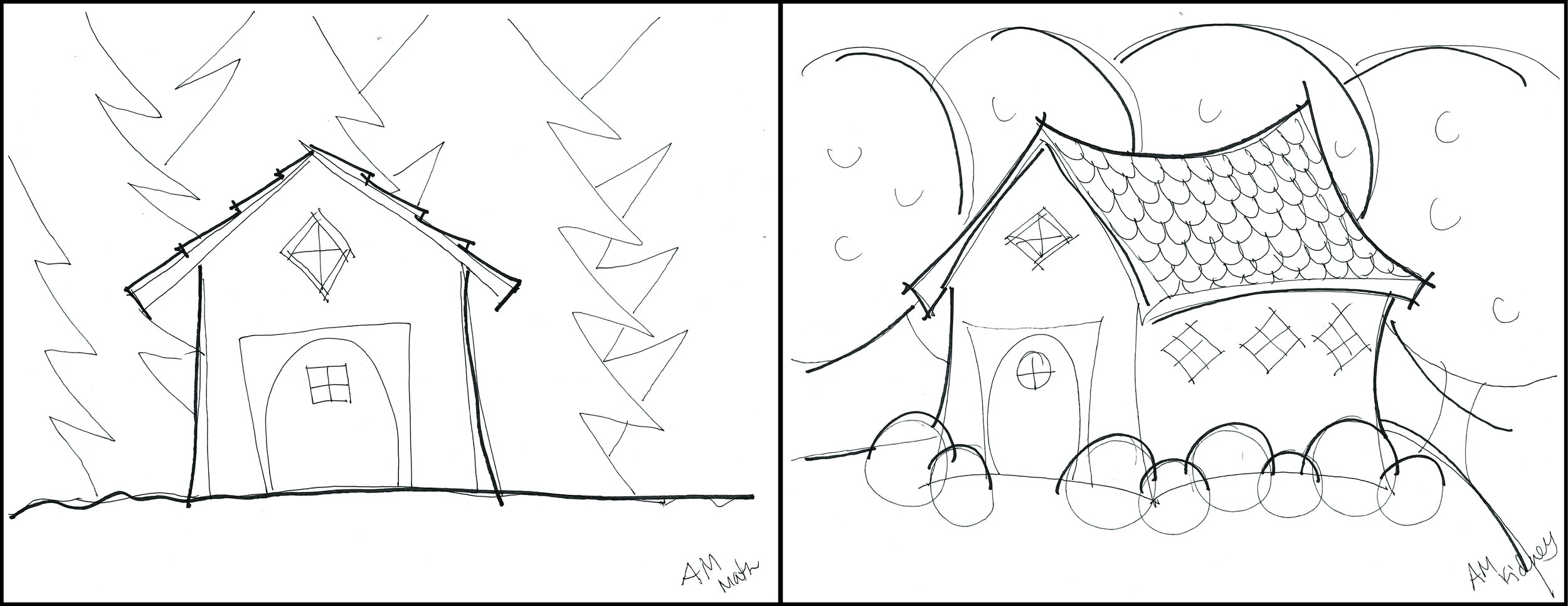

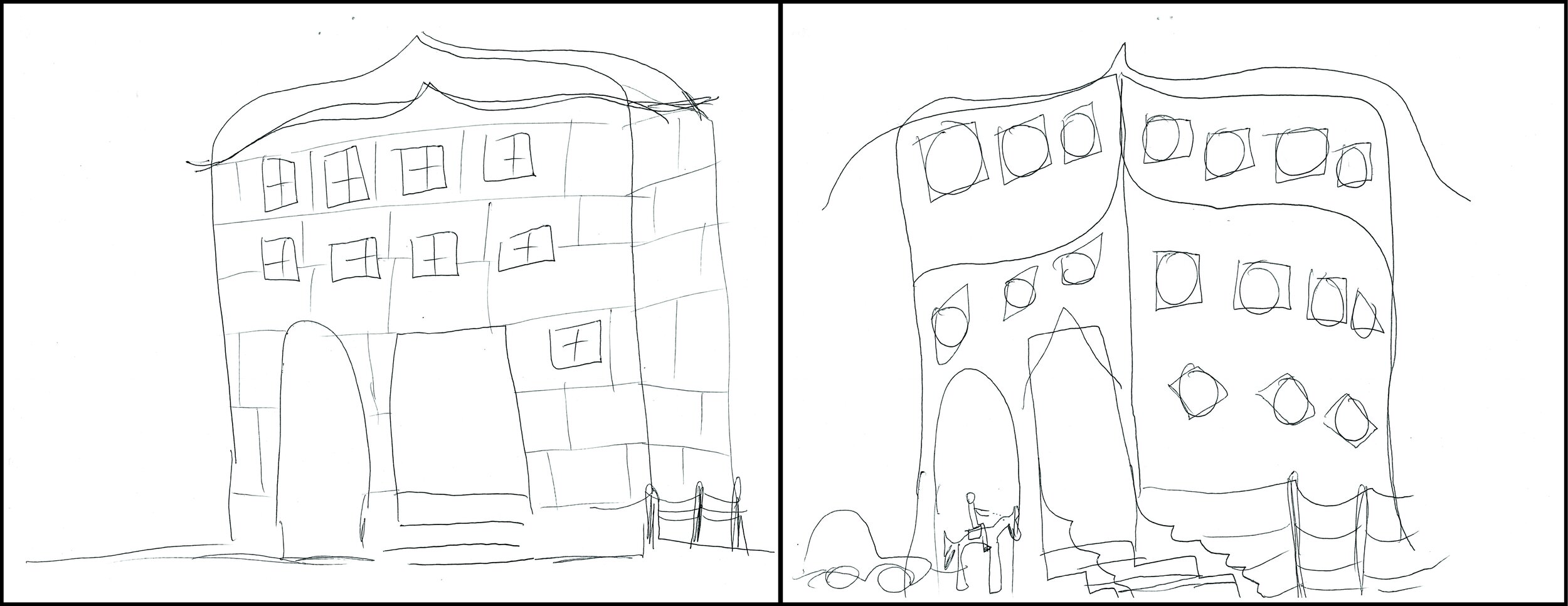

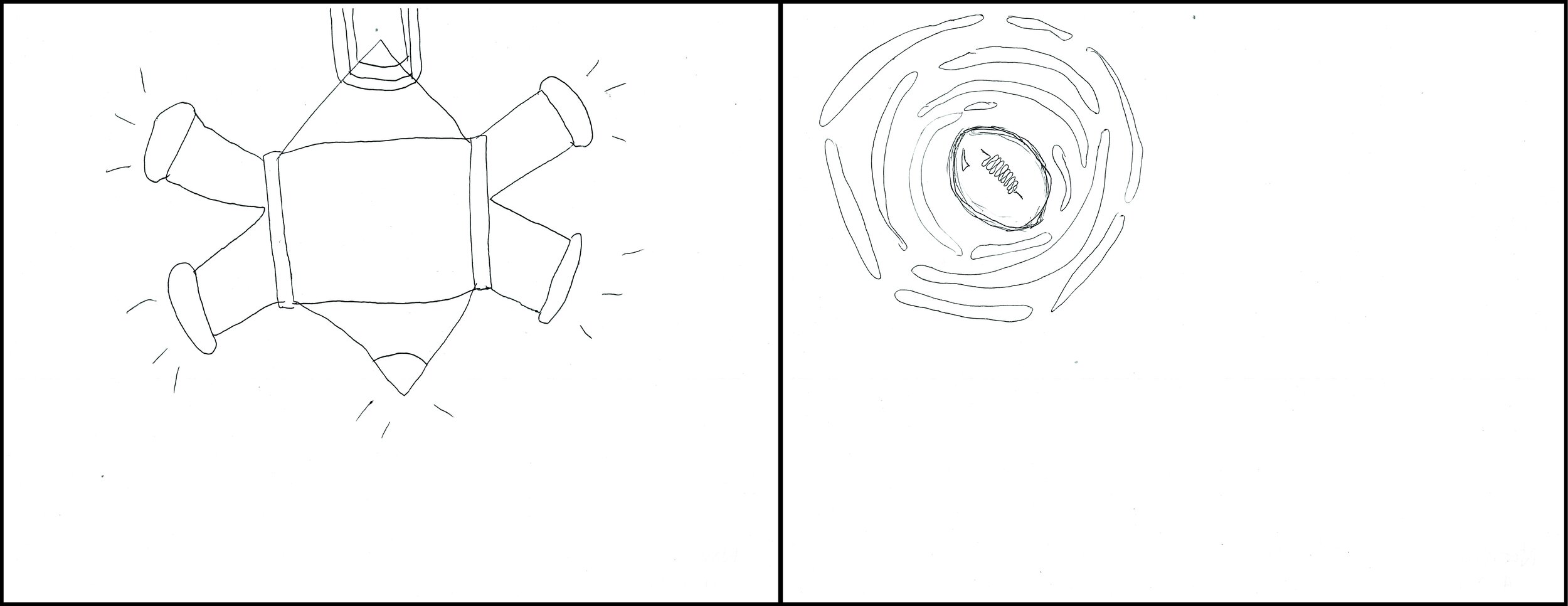

Since 2008, Cranz has collected approximately 200 pairs of drawings from students in her annual Body Conscious Design seminar. These drawings support a published hypothesis that deliberately priming the brainstem and limbic system through somatic exercises can influence perception and creativity in drawing and design.⁴ Each research participant makes two pairs of drawings, either of handles and lamps, or of buildings and urban plazas—elements of the built environment at different scales with which we commonly interact. Participants produce the first “cortical” drawings after stimulating the neocortex with math problems; they create the second “subcortical” drawings after stimulating the brainstem and limbic system with exercises that focus awareness on body organs.

How the Body Makes Marks selects drawings for their visual interest and humour, and especially for the often surprising differences between the two drawings in a pair. When you look at the drawings, ask: which ones are small, angular, and flat? Which ones tend toward largeness, curviness, and three-dimensionality? How does each drawing in a pair relate to its environment? The built environment? The natural environment? The page itself?

First, the exhibition presents handles and lamps: architectural elements that we hold in, grasp with, and operate by our hands. Then it shows buildings and urban plazas: architectural environments that hold and contain us. Finally, an interactive section invites you to contribute your own somatic drawings to the exhibition’s imagination of what can change in the built environment, and in us, when we design with and for the whole body.

WHAT IS SOMATICS?

The term somatic comes from the Greek sōma, “body,” and sōmatikos, “of the body.” Somatics is the study of the body—but not from the outside. Rather, somatics studies the body as perceived from within, by the person who lives and moves in that body.⁵

Although somatics as a field of education and research was not named until the 1970s (by Thomas Hanna), it emerged at the end of the 19th century. Early somatic practices pioneered by F.M. Alexander, Moshé Feldenkrais, Ida Rolf, and others rejected Victorian strictures on the body.⁶ They integrated movement methods including yoga, qi gong, and judo—discovered and adopted through increasingly available opportunities for travel and transmigration from Asia to Europe and the Americas—with new ideas and theories in philosophy, psychology, cultural studies, education, and medical research.⁷

All somatic practices require that people take time to breathe, feel, and listen to their bodies, often by beginning with conscious relaxation on the floor or on a bodywork table. From here, people pay attention to bodily sensations emerging from within and move slowly and gently, either independently or with the guidance of a teacher or professional. Movements can range from the subtle motions initiated by the breath, face, and postural muscles to large gestures made with the head, neck, and limbs. Through somatic experiences, people can heighten their sensory and motor awareness toward improved self-knowledge.⁸

Not all body-focused practices can be considered somatic practices. Somatics considers both the individual and the collective as made up of many aspects—biological, evolutionary, emotional, psychological—which are shaped by and can adapt to historical, social, and cultural norms and forces. Somatics understands that through resilience and survival strategies, social and cultural practices become our automatic responses, habits, relational patterns, world views, and self-concepts. These come to feel familiar and natural even when they do not line up with our anatomy or values. Somatic practices call awareness to the default patterns we embody; further, they help deconstruct them in order to manifest new, sustainable ways of thinking, feeling, acting, and relating in alignment with personal and collective values and ideals.⁹

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF SOMATICS FOR ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN?

“When a human soma looks at itself in a mirror, it sees a body—a third person, objective structure. But what is this same body when looked at from an internal, somatic perspective? It is the unified experience of self-sensing and self-moving.”

— Thomas Hanna¹⁰

How could built environments change if they were designed from the inside, as extensions of our bodies? How would users’ experiences of these environments change? How would users themselves change?

Everyone can benefit from somatic practices. Designers and architects can use somatic awareness to understand where, why, and how built environments fight against users or force users to fight against ourselves. What is it about a handle that makes it uncomfortable or comfortable to hold? What qualities of a lamp make the light unpleasant or pleasant? How do buildings negatively or positively affect people’s moods? Why are some public spaces more popular than others? With this understanding, designers and architects can envision new environments and make changes to existing ones with a different kind of attention—a somatic attention—to material, form, surface, space, and light.

Designing from a somatic perspective does not by any means need to forsake aesthetic appeal. Instead, as these exhibited drawings suggest, somatic designs can actually amplify the visual impact of objects, places, and spaces. They depart from cultural norms in architecture and environmental design, and they reflect the human forms that make and use them. Importantly, the visual impact and functionality of somatic designs are not mutually exclusive; appearance and function are wholly integrated in an effort to facilitate a fuller expression of users’ own embodied awareness and vitality.

— Chelsea Rushton, Curator

NOTES

¹ Rena Czaplinska-Archer, “Time for Drawing: On Coming to Our Senses, Personal View,” Rena Architects.

² Ibid: pg. 3.

³ Galen Cranz and Leonardo Chiesi, “Design and Somatic Experience: Preliminary Findings Regarding Drawing Through Experiential Anatomy,” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 31 no. 4 (Winter, 2014): pg. 323-24.

⁴ Ibid: pg. 324.

⁵ Thomas Hanna, “What is Somatics?,” Journal of Behavioral Optometry 2 no. 2, (1991): pg. 32.

⁶ Martha Eddy, “A brief history of somatic practices and dance: historical development of the field of somatic education and its relationship to dance,” Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices 1 no. 1 (2009): pg. 6.

⁷ Ibid: pg. 7.

⁸ Ibid: pg. 6-8.

⁹ “Theory: What is a Politicized Somatics?,” Generative Somatics: Somatic Transformation and Social Justice, par: 2-5.

¹⁰ Thomas Hanna, “What is Somatics?,” Journal of Behavioral Optometry 2 no. 2, (1991): pg. 33.

THE DRAWINGS

HANDLES

When you look at these pairs of drawings, remember that the cortical drawing is on the left and the subcortical drawing is on the right. Keep the following questions in mind when you look at these handles.

Some of the handles in these drawings are the handles on cups, doors, bikes, canes, suitcases and briefcases, vessels…

Where else do you interact with handles in daily life?

Is the handle you are looking at attached to anything?

Is the handle presented in context with a surrounding environment?

Is the handle vertical, horizontal, or neither?

Is the handle presented in relationship to a hand?

At what scale has the handle been drawn?

Is the handle straight or curved?

Does the handle have notches for fingers?

How representational or abstract is the handle?

Have you ever encountered a handle that looks like this?

Can you imagine holding this handle? How does it feel in your hand?

LAMPS

When you look at these pairs of drawings, remember that the cortical drawing is on the left and the subcortical drawing is on the right. Keep the following questions in mind when you look at these lamps.

Some of the lamps in these drawings are table lamps, floor lamps, sconces, lanterns...

Where else do you encounter artificial lighting in daily life?

How many light bulbs does the lamp you are looking at have?

Do you see light coming out of the lamp? How is the light depicted? What kind or quality of light do you think it is?

Is there shadow around the lamp? How is the shadow depicted?

Is the lamp presented in context with a surrounding environment?

Does the drawing depict how the lamp turns on and off? If so, how easy or awkward does it look to do so?

How do the proportions of the lamp’s parts relate to each other?

Can you see inside the external structures of the lamp?

How representational or abstract is the lamp?

Have you ever encountered a lamp that looks like this?

Can you imagine using this lamp? How does it make your body feel?

BUILDINGS

When you look at these pairs of drawings, remember that the cortical drawing is on the left and the subcortical drawing is on the right. Keep the following questions in mind when you look at these buildings.

Some of the buildings in these drawings are apartment buildings, houses, office buildings, low storey buildings, high storey buildings…

What other kinds of buildings do you encounter in daily life?

What kind of buildings are depicted in each pair of drawings? Are they the same kind of buildings in both drawings or different kinds of buildings?

Do the drawing’s lines and shapes indicate the building’s materials?

What is the building’s relationship to its surroundings?

What is the building’s relationship to natural elements?

What is the building’s relationship to daylight? Does it have windows? How many windows? What size windows?

Is there a visible entrance to each building? What is its scale?

Is the building shown with human users? What is the scale of users to building? What are the users doing?

What is the perspective of the drawing? Is the building shown from above? From ground level?

Does the drawing show the outside and the inside of the building? Only the outside? Only the inside?

Have you ever encountered a building that looks like this?

Can you imagine using this building? How does it make your body feel?

URBAN PLAZAS

When you look at these pairs of drawings, remember that the cortical drawing is on the left and the subcortical drawing is on the right. Keep the following questions in mind when you look at these urban plazas.

Some of the plazas in these drawings are city blocks, building courtyards, or other high density urban plazas; some are low density urban plazas; some are suburban green spaces...

What other kinds of plazas do you encounter in daily life?

What is the perspective of the drawing you are looking at? Is the plaza shown from above? From ground level?

How is access to the square depicted? Road? Sidewalk? Pathway?

What is the proportion of green space to paved space?

What natural elements are depicted in the plaza? Trees? Shrubs? Flowers? Water?

Is the land flat or contoured? Are there slopes or hills? Is the square sunken into the ground?

Are there people in the space? How are they depicted in relationship to the space? What are they doing?

What is the scale of humans or human elements (such as benches, chairs, tables) compared with natural elements?

Are there animals in the space?

What kinds of surroundings are depicted in relationship to the plaza?

Have you ever encountered a plaza that looks like this?

Can you imagine using this plaza? How does it make your body feel?

THE SOMATIC DRAWING STATION

This is a sound recording of an experimental protocol similar to the one used by Galen Cranz to collect the drawings in this exhibition. You can use it to produce one pair of your own cortical and subcortical drawings depicting handles, lamps, buildings, urban plazas, or another element of the built environment you would like to design with somatic awareness.

Completing this protocol will take approximately 20 minutes.

BEFORE YOU BEGIN:

- Silence your phone and put it out of sight

- Choose what you are going to draw

- Write your name and the date on two sheets of the paper provided

- Turn both sheets of paper over so you are prepared to draw on the blank sides

NOW YOU ARE READY TO LISTEN.

When you are prompted by the recording to complete a series of mathematical exercises, please solve these equations—without using a calculator:

639 215 137 924

+ 326 - 146 x 6 ÷ 3

WHEN YOU FINISH THE PROTOCOL:

- Label your drawings “cortical” and “subcortical”

- Share your drawings on Instagram by tagging @galencranzconsulting, and by using the hashtag #howthebodymakesmarks

YOUR DRAWINGS

These are drawings made by visitors to and participants in the exhibition both at UC Berkeley and online, as well as participants to other events where we have presented this research on drawing and somatic experience. We would love to see your drawings and feature them here. Post them on Instagram by tagging @galencranzconsulting, and by using the hashtag #howthebodymakesmarks, or contact us to send them by email.